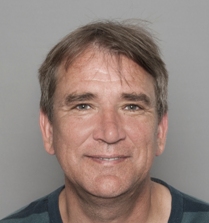

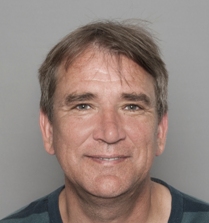

Mark Garnett argues that much of the controversy over the position of Prime Minister arises from a confusion between the occupant’s inescapable political prominence and their often limited ability to achieve positive policy outcomes. The nature of the job may have therefore become a deterrent for politicians who are motivated by a desire to serve the public, and opened the way for those with much less laudable motivations.

Mark Garnett argues that much of the controversy over the position of Prime Minister arises from a confusion between the occupant’s inescapable political prominence and their often limited ability to achieve positive policy outcomes. The nature of the job may have therefore become a deterrent for politicians who are motivated by a desire to serve the public, and opened the way for those with much less laudable motivations.

The government has recently decided it will not be starting an inquiry into the UK’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic for months. Still, well in advance of any such enquiry, Boris Johnson’s admirers already have their narrative in place. They are willing to concede that some missteps occurred in the early stages, and that Johnson’s messaging was inappropriate at times. But this was only to be expected, given the unprecedented emergency; and even while making mistakes, Johnson was extremely clear-sighted in his strategy of vaccine procurement.

In any case, Johnson showed a readiness to learn from his experiences – not least because of his own near-fatal encounter with the virus. Over-promising and unsuitably militaristic language gave way to ‘realistic’ planning and sober pronouncements. The improvement in tone and decision-making seemed to coincide with the departure of Dominic Cummings from Johnson’s entourage. Despite his admirable loyalty to his fellow Brexiteer, Johnson was wise enough to recognise the need for more cautious counsellors to confront this new national challenge.

The story, transmitted by Johnson’s media allies, will be widely accepted even if some voters prove to possess longer memories. However, even if one accepts that Johnson has finally mastered his unexpected role of the pandemic premier, it is pertinent to ask whether he has the skillset and disposition to be a satisfactory Prime Minister for ‘normal’ times. Normal, of course, now means ‘post-Brexit’; and Johnson’s handling of this topic will be vulnerable to close inquiry long after the pandemic has been ‘sent packing’ (as he put it). Even before Brexit, it could be argued that it has become impossible to perform the job of British Prime Minister with ‘success’ in common-sense terms – e.g. the fulfilment of a constructive policy programme.

In a recently published book, I have identified several well-established trends which have combined to make the role of Prime Minister ‘dysfunctional’. Among these are a volatile electorate, no longer constrained by considerations of social class, which has been encouraged by a celebrity-obsessed media to base its choices on perceptions of party leaders. However, in the UK context, this has been augmented by conscious decisions of governments since 1979 to ‘hollow-out’ and part-privatise the state. One consequence is that government departments (except the Treasury) no longer confer independent political status on ministers, leaving them as little more than cyphers, interchangeable at the whim of the Prime Minister. Furthermore, since departments can no longer guarantee the successful implementation even of well-considered policy ideas, governments have become increasingly (at times pathetically) reliant on unelected appointees – spin doctors and special advisers – to create the impression of success.

The impulse to confuse the impression of success with real achievement is accentuated at the heart of government by a recognition that, in the hollowed-out world of Westminster and Whitehall, the only serviceable ‘performance indicator’ for a government is whether or not it is re-elected. Here again the Thatcher governments set the trend, by readily interpreting their successive victories at the polls over hopelessly divided opponents as a triumphant vindication of policies which, even today, are bearing bitter fruits. The presentation of parliamentary elections as ‘presidential’ contests – with ministerial colleagues now wheeled in for supportive media appearances on a rota basis rather than commanding public attention in their own right – means that, as in 2019, a victory of the ‘less unpopular’ candidate for the top job can be spun as if it bestows an unanswerable personal mandate for five more years of incompetence.

My critique of the role of Prime Minister was developed when Theresa May looked certain to win a general election at a time of her own choosing (despite the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act). Her replacement by Boris Johnson threatened to make warnings about the dysfunctionality of the British premiership seem like statements of the obvious. Johnson, after all, was chosen to succeed May because he exhibited only one of the qualities which might be helpful for a Prime Minister – the potential to win votes for the ruling party. Johnson’s aptitude even on this score is contested by a substantial segment of the voting population; but it was taken for granted by a clear majority of Conservative members who made the final choice in July 2019; for them this single attribute is enough.

A Prime Minister whose position depends on vote-winning potential is only as good as their latest opinion poll. Even as Johnson’s defence against impending enquiries was being leaked to the media, he was providing evidence that (like all of his post-Thatcher predecessors) he was determined to make life more difficult for the holder of his position once ‘normality’ returned. Thus, the attack on the state is set to continue, through the dispersal of Whitehall departments from London. Clearly designed to make the rest of the UK imagine that the English care about them, the gimmick nevertheless shows Thatcher-like contempt for the civil service, whose focus on the long-term national interest is an irritant for any government which is fixated on the need for ‘validation’ through re-election.

In a meeting with backbenchers in March, Johnson revealed the extent of his adherence to the Thatcherite ideology, attributing the success of the UK’s vaccine programme to capitalism and greed. The media seem to have treated this as a gaffe worthy of one day’s headlines, but his remark was a direct insult to the public servants in the NHS who are the real heroes of the pandemic. This also coincided with allegations that Johnson’s predecessor, David Cameron, has attempted to use his influence on behalf of a friend in the ‘greed’ sector. The stories raised fears that even Prime Ministers who are actuated to some extent by a sense of public duty have adopted the post-Thatcherite view that the hollowed-out state still serves a useful purpose in generating easy profits for favoured clients.

While basking in his victory in the vaccine wars against the EU, Johnson has also been depicted as a national embarrassment in the published diaries of Alan Duncan, a former ministerial colleague. Those who know Johnson best, it seems, respect him least – including Jennifer Arcuri, whose revelations indicate at best an intensely relaxed approach to the ineffectual rules governing conduct in a public office.

Nevertheless, Boris Johnson is not the problem. That lies in the nature of the position he currently holds – bloated by public prominence to an extent way beyond its capacity to deliver constructive policies either at home or (especially) abroad. By and large, the British public has met the challenge of COVID-19 with remarkable patience and resilience. But, in an uncertain and hazardous world, the nation required leadership which could adjust rapidly to the demands of a disaster which, however unprecedented, was far from being unpredictable. Throughout his career, Johnson has lost no opportunity to flatter the solid good sense of the British people. With crucial elections pending for councils and devolved institutions, the country’s voters have a chance to show that they, too, have learned from their experiences of government decisions since the EU referendum.

_____________________

Mark Garnett is Senior Lecturer at Lancaster University.

Mark Garnett is Senior Lecturer at Lancaster University.

Featured image credit: Number 10 on Flickr licensed under a CC-BY-NC-ND licence.