The government’s anti-immigration rhetoric is currently stronger than ever and the value of multiculturalism is increasingly challenged. Eleni Andreouli writes that instead of protecting social cohesion, this stigmatisation of migrants leads to misrecognition and heightened intergroup tensions.

The government’s anti-immigration rhetoric is currently stronger than ever and the value of multiculturalism is increasingly challenged. Eleni Andreouli writes that instead of protecting social cohesion, this stigmatisation of migrants leads to misrecognition and heightened intergroup tensions.

Britain’s approach towards immigration is driven by two seemingly contradictory aims. On the one hand, the government is clearly engaged in an anti-immigration rhetoric seeking to substantially reduce immigration, both from outside and from within the EU. On the other hand, the government also seeks to enhance integration through an emphasis on commonality and sharedness. However, both policies point to the same direction. Migrants are doubly otherised: they are not only seen as a burden to the economy, they are also seen as a threat to national solidarity. Insights from social psychology indicate that this can reduce cohesion and heighten intergroup tensions.

Immigration is a burning topic in UK politics. Within a framework of ‘managing migration’ and aiming to restrict net migration to tens of thousands, the British government has brought in several restrictions for migrants wishing to move to this country. Britain’s ‘points-based system’, initially introduced by Labour, means that migrants’ potential to contribute to the economy is now scrutinised. The government is becoming increasingly selective on who is allowed to migrate to the UK. And ultimately it is the richest migrants that Britain wants to attract, closing the door to others. It is telling that only so called ‘high valued migrants’ can come to the UK without a job offer – for example investors who are willing to invest £1 million in the UK.

Even migrants from within the European Union face a hostile political environment. Just before January 2014, when transition controls for A2 migrants from Bulgaria and Romania were about to be lifted, the government considered putting in place negative advertising of the UK in order to deter immigration from Bulgaria and Romania. What is more, as a last minute attempt to assuage public fears about A2 migrants, David Cameron recently introduced welfare restrictions for European migrants.

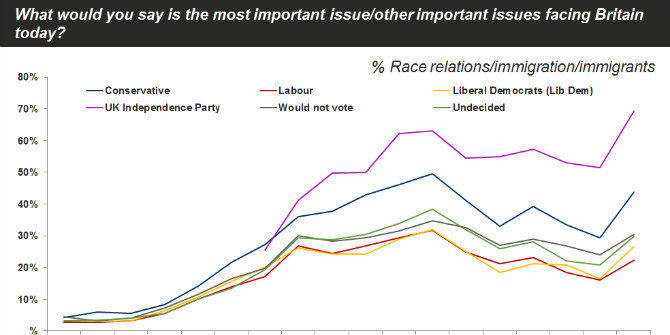

This anti-immigration rhetoric is employed by both the left and the right of the political spectrum. Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, seemed to share similar concerns when he said that Labour got it wrong on its handling of A8 immigration – i.e. when the Labour government chose not to impose transition controls for A8 migrants.

The anti-immigration rhetoric of British politicians is based on the assumption that migrants are a burden to British economy. More than that, it is assumed that migrants are after Britain’s welfare. Terms such as ‘benefit tourism’ are now part of the political vocabulary when it comes to immigration. The emphasis on assessment, conditionality and deterring abuse of immigration policy creates a distinction between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ migrants, or between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ migrants – echoing in a way the unfortunate but popular distinction between ‘genuine’ and ‘bogus’ asylum seekers.

On the other hand, the British state appears committed to enhance social cohesion and integration. During the Labour government, community cohesion became a catchphrase for reducing intergroup tensions – particularly following the riots of 2001 but also due to increased concerns about ‘home-grown terrorism’ after 7/7. A social cohesion agenda was implemented at the time in different policy areas. Schools, for example, were expected to promote community cohesion through citizenship education.

Immigration is another key area where cohesion strategies have been introduced. Migrants wishing to naturalise as citizens need to pass the Life in the UK test and attend a citizenship ceremony where they have to pledge their allegiance to the Queen and swear or affirm their loyalty to the UK. In a similar vein, the Coalition government has recently developed a strategy for enhancing integration. Integration is seen in terms of developing a common ground defined as “a clear sense of shared aspirations and values, which focuses on what we have in common rather than our differences”.

There is an important shift in emphasis in these recent approaches to diversity: from recognising difference with multicultural policies, to emphasising ‘shared British values’ and commonality within a cohesion or integration agenda. While Britain has traditionally been seen as multiculturalist compared to other Western European countries (Germany and France are a common example of assimilationism), the value of multiculturalism is now increasingly challenged.

This was made clear in David Cameron’s speech in Munich Security Conference in 2011. In that speech Cameron argued that multiculturalism encourages ‘different cultures to live separate lives’ and allows for ‘segregated communities’ to behave ‘in ways that run completely counter to our values’. Multiculturalism has become a taboo word in contemporary Britain. The sociologist Steven Vertovec was right when he said no politician wants to be associated with the M-word. Put differently, difference is bad and sameness is good.

Can this approach promote cohesion and integration? Some insights from social psychology may be useful here. Back in 1934, George Herbert Mead, a pioneer social psychologist, argued that the development of the self is contingent upon recognition from others. That identity is a matter of both how we see ourselves and how others see us has since become well-established in psychology. Drawing on this idea, Charles Taylor argued in his Multiculturalism and the Politics of Recognition that, in diverse societies, lack of recognition or misrecognition can become forms of oppression.

Acculturation research further suggests the specific integration policies adopted by governments influence how migrants acculturate and how they relate to other groups. Successful integration on the part of migrants depends on multiculturalism on the part of receiving societies. It is lack of recognition that can lead to inward-looking identities and segregation. Stigmatising migrants as a burden to the economy further enhances misrecognition.

Instead of promoting cohesion and the development of a super-ordinate British identity, the politics of sameness and assimilation promote polarisation between ‘us’ and ‘them’. And it is polarisation that fuels intergroup conflict. Solidarity and multiculturalism are not opposites: it is only through meaningful engagement with others that we can develop secure identities and positive social relationships. Solidarity develops through recognition of diversity, not its denial. The demonisation of multiculturalism and of immigration can only limit Britain’s ability to develop as a cohesive and inclusive society.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Dr Eleni Andreouli is Lecturer in Psychology at the Open University. Her primary research interests lie in the social psychology of citizenship, immigration and identity in diverse societies.

War is peace and freedom is slavery

It couldn’t be that by continuing to foist unprecedented social change for which there was never any democratic mandate on the British people that the mass immigration lobby is the one which is undermining social cohesion, could it?

You complain about the politicians but they are only reacting to the enormous public opposition to this highly illiberal policy. People have had enough. And the opposition to it stretches across the different ethnicities.

Your desperation to keep this agenda going is quite frightening. One can see how the liberal left is as much a threat to democracy as the super-rich are.

“Insights from social psychology indicate that this can reduce cohesion and heighten intergroup tensions.” It’s blindingly obvious to anyone with an IQ above zero that anti-immigrant sentiment will “heighten intergroup tensions”.

And the rest of Eleni Andreouli’s article consists of similar statements of the obvious, or false logic.

But there are any number of jobs in academia which consist of talking twaddle, so Elani Andreouli is onto a good thing there.

There are so many untold stories in the news media. Not a mention of the failings by banks towards small businesses – these are people’s social mobility? Given that the surge of suicides between 2007 and 2010 is another untold story in the news media, should we not be looking to understand and discuss the relationship between the strong upwards social mobility efforts that ‘ordinary’ people make to develop themselves in business… and the failure from banks (and governments) of said viable businesses and people, the loss of homes and possible psychological challenges that creates unemployment? Should we not also understand the importance of measuring the substantial impact this has on family members, neighbours, communities and society overall?

If we are bold to acknowledge this relationship between all of the above and the strong desire for people to improve their Upwards Social Mobility amid such failings, can we then understand the anger and frustration of allowing those outside the Country to reduce the employment market in the UK by taking the job roles that UK residents should be doing.

This debate always seems to have a simply and narrow remit when discussed on TV. I suggest that the fears, anger and frustration are much more broader and reflect many of the failings I have mentioned above.