Last month the eurozone returned to recession, three years after it emerged from the deep recession of 2008-09. Paul De Grauwe argues that the current situation has been produced by policy failures at the beginning of the crisis. The best initial policy would have been for the eurozone’s creditor countries to increase spending, while the struggling periphery countries implemented austerity measures. The budget-balancing policies of creditor countries have instead created an asymmetric adjustment process in which most of the adjustment has been carried by debtor countries such as Spain, Greece and Ireland. One mechanism for returning the eurozone to growth may be for states such as Germany, Finland and the Netherlands to maintain small budget deficits while keeping a constant debt to GDP ratio.

Last month the eurozone returned to recession, three years after it emerged from the deep recession of 2008-09. Paul De Grauwe argues that the current situation has been produced by policy failures at the beginning of the crisis. The best initial policy would have been for the eurozone’s creditor countries to increase spending, while the struggling periphery countries implemented austerity measures. The budget-balancing policies of creditor countries have instead created an asymmetric adjustment process in which most of the adjustment has been carried by debtor countries such as Spain, Greece and Ireland. One mechanism for returning the eurozone to growth may be for states such as Germany, Finland and the Netherlands to maintain small budget deficits while keeping a constant debt to GDP ratio.

This article first appeared on the LSE EUROPP blog

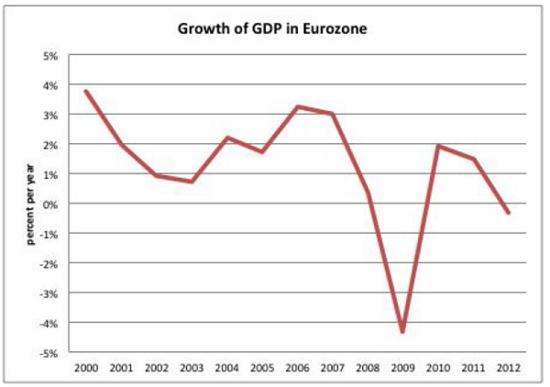

The risk of a double-dip recession in the eurozone had been increasing during the last few months. Figure 1 shows the growth rate of GDP in the eurozone. It can be seen that after a recovery from the deep recession of 2008-09, the eurozone’s GDP growth has been turning again into negative territory since the second part of 2012.

The renewed decline in the growth rates of GDP in the eurozone has the effect of automatically increasing government budget deficits and putting pressure on national governments to avoid an increase in these deficits. As a result, fiscal policies are tightened even further. The risk is that pro-cyclical budgetary policies will push GDP growth rates in 2013 firmer into negative territory, exacerbating the current recession. The asymmetric structure of macroeconomic adjustments in the eurozone has led it towards this situation. A more symmetric approach of adjustment may be a way to avoid it.

Figure 1

Source: European Commission, AMECO.

Asymmetries in macroeconomic adjustments in the eurozone

It is no exaggeration to state that macroeconomic policies in the eurozone have been driven by sentiments in financial markets. Some countries (mainly the southern European countries) have been pushed into bad equilibria characterised by high interest rates and intense pressures to redress budget deficits by intense austerity programmes. Other countries (mainly northern European countries) have gently been pushed into good equilibia, characterised by historically low interest rates and the relative comfort that can be derived from them. The southern European countries (including Ireland) are also the economies that have accumulated current account deficits, while the northern European countries have built up current account surpluses.

The best initial policy would have been for the debtor countries to reduce and for the creditor countries to increase spending. Instead, under the leadership of the European Commission, tight austerity was imposed on the debtor countries while the creditor countries continued to follow policies aimed at balancing the budget. This has led to an asymmetric adjustment process in which most of the adjustment has been done by the debtor nations. The latter countries have been forced to reduce wages and prices relative to the creditor countries (an ‘internal devaluation’) without compensating wage and price increases in the creditor countries (‘internal revaluations’). Figures 2 and 3 graphically illustrate these trends.

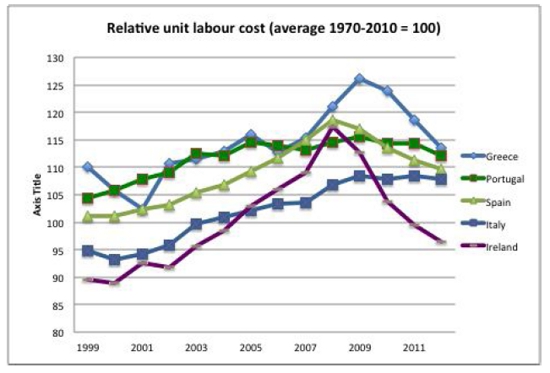

Figure 2. Relative unit labour costs in Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy and Ireland

Source: European Commission, AMECO.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the relative unit labour costs of the peripheral debtor countries (where we use the average over the 1970-2010 period as the base period). Two features stand out. First, from 1999 until 2008-09, one observes the strong deterioration of these countries’ relative unit labour costs. Second, since 2008-09, quite dramatic turnarounds of the relative unit labour costs have occurred (internal devaluations) in Ireland, Spain and Greece, and to a lesser extent in Portugal and Italy.

These internal devaluations have come at a great cost in terms of lost output and employment in the debtor countries. As these internal devaluations are not yet completed (except possibly in Ireland), more losses in output and employment are to be expected.

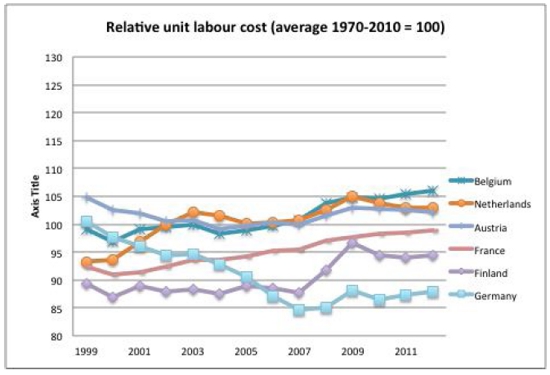

Is there evidence that such a process of internal revaluations is going on in the surplus countries? The answer is given in Figure 3, which presents the evolution of the relative unit labour costs in the creditor countries. We observe that since 2008-09, there is very little movement in these relative unit labour costs in these countries. The position of Germany stands out. During 1999-2007, Germany engineered a significant internal devaluation that contributed to its economic recovery and the build-up of external surpluses. This internal devaluation stopped in 2007-08. Since then no significant internal revaluation has taken place in Germany. We also observe from Figure 3 that the other countries remain close to the long run equilibrium (the average over 1970-2010) and that no significant changes have taken place since 2008-09.

Figure 3. Relative unit labour costs in Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria, France, Finland and Germany

Source: European Commission, Ameco.

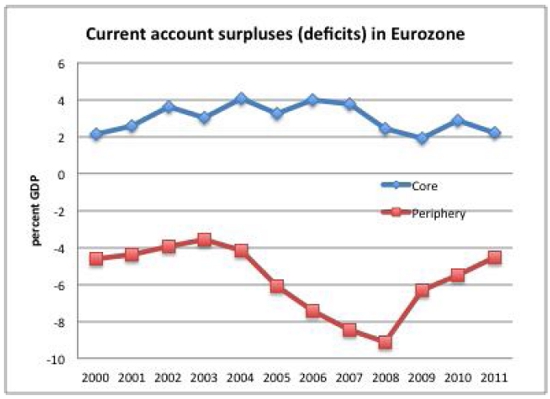

Figure 4 shows a similar asymmetry in the adjustment process of current account imbalances. We show the current account positions of the surplus and deficit countries. We observe the significant deterioration of the current account position of the deficit countries during the ‘bubble years’ followed by an equally significant improvement in the current account position. No such movements are observed in the surplus countries leading to the conclusion that most of the adjustment in the external imbalances within the eurozone has been made by the peripheral deficit countries. From the preceding analysis, one can conclude that the burden of the adjustments to the imbalances in the eurozone between the surplus and the deficit countries is borne almost exclusively by the deficit countries in the periphery. This asymmetry produces a deflationary bias in the eurozone as a whole. Yet it could be done differently. A more symmetric macroeconomic policy that reduces the deflationary bias can be implemented.

Figure 4

Source: European Commission, AMECO.

How to recover from the double-dip recession

A symmetric approach should start from the different fiscal positions of the member countries of the eurozone. This difference is shown in Figures 5 and 6, which present the government debt ratios of two groups of countries in the eurozone, the debtor and the creditor countries. One observes from these figures that while the debtor countries have not been able to stabilise their government debt ratios (in fact, these are still on an explosive path), the situation of the creditor countries is dramatically different. With the exception of France, the latter set of countries has managed to stabilise these ratios. This opens a window of opportunity to introduce a rule that can contribute to more symmetry in the macroeconomic policies in the eurozone.

Here is the proposed rule. The creditor countries that have stabilised their debt ratios should stop trying to reduce their budget deficits further now that the eurozone is entering a double-dip recession. Instead they should stabilise their government debt ratios at the levels they have achieved in 2012. The implication of such a rule is that these countries can run small budget deficits and yet keep their government debt levels constant. Germany, in particular, which today has almost achieved a balanced budget, could increase its budget deficit to close to 3 per cent while keeping its ratio of debt to GDP constant. Other creditor countries – Belgium, Netherlands, Finland and Austria – could be urged to stop adding new austerity measures without leading to an increase in their debt-to-GDP ratios.

Whether such a rule will be implemented very much depends on the European Commission. The latter should invoke exceptional circumstances: i.e. the start of a recession that is hitting the whole eurozone and threatens to undermine the stability of the currency area, and urge the creditor countries to temporarily stop trying to balance their budgets. As an alternative rule, the European Commission should convince the creditor countries that it is in both their and the eurozone’s interest that they stabilise their government debt ratios instead.

The more symmetric budgetary policies advocated here would go some way toward reducing the deflationary bias that has been instilled in the macroeconomic policies pursued in the eurozone since the start of the debt crisis, and which have pushed the eurozone into a double-dip recession.

This article is based on material originally compiled for the CEPS commentaries series.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Paul De Grauwe is the John Paulson Chair in European Political Economy at the LSE’s European Institute. Prior to joining LSE, he was Professor of International Economics at the University of Leuven, Belgium. He was a member of the Belgian parliament from 1991 to 2003. His research interests are international monetary relations, monetary integration, theory and empirical analysis of the foreign-exchange markets, and open-economy macroeconomics. His published books include The Economics of Monetary Union (OUP, 2010), and (with Marianna Grimaldi), The Exchange Rate in a Behavioural Finance Framework (Princeton University Press, 2006).