The Liberal Democrats’ decline and fall is not just a result of political miscalculation over the last five years, but also reflects changes in the overall party system. The growing polarisation in the British party system, with the rise of UKIP, the SNP and Greens, itself played a factor, argues Ben Margulies.

The Liberal Democrats’ decline and fall is not just a result of political miscalculation over the last five years, but also reflects changes in the overall party system. The growing polarisation in the British party system, with the rise of UKIP, the SNP and Greens, itself played a factor, argues Ben Margulies.

In contemporary British politics, the story of the Liberal Democrats is usually framed as one of betrayal or misjudgment. Associated for many years with the centre-left, the party entered the 2010 general elections as the champion of a new politics, with a fresh young leader and a popular pledge to abolish tuition fees. Five years later, tuition fees had tripled, the banners of new politics had been claimed by others, and the party found itself with only eight seats in the House of Commons.

It is clear that the Lib Dems were the victims of their own political miscalculations. Though they portrayed themselves as doughty campaigners for social justice on the campaign trail and in the coalition cabinet, the Lib Dems never recovered from their association with the tuition-fee hike or Conservative-led austerity politics. They played the game, and lost.

But the Liberal Democrats’ decline and fall also reflects changes in the overall party system. As I demonstrate in two articles, liberal parties do not always prosper in circumstances where the party system has become highly polarised. As UKIP, the SNP and the Greens grew stronger during the second half of the 2010-15 Parliament, it may be that the process of fragmentation their success unleashed diminished the Lib Dems’ electoral fortunes, contributing to the party’s electoral debacle in May 2015.

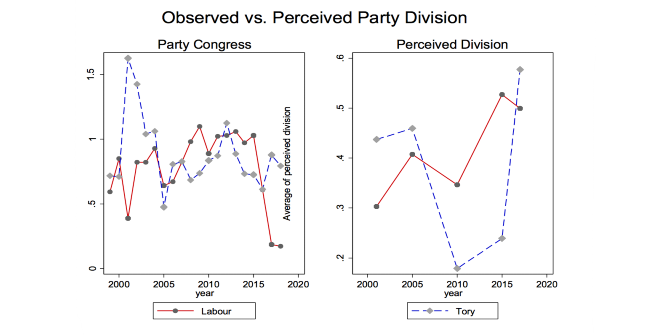

Nagel and Wlezien, in a study of post-war Britain, found that the Liberals/Alliance/Liberal Democrats were generally located in the centre of a stable two-and-a-half or three-party system. In their work, they found that, whenever Labour and the Conservatives moved towards either extreme of the left-right spectrum – whenever they left more space in the political centre – the Liberal Democrats increased their vote share. My own work, published in Comparative European Politics, confirms that this is a global trend. In advanced democracies, when conservative parties move to the right, liberal parties show a modest tendency to gain votes. When social-democratic parties move to the left, the liberals also gain.

Nagel and Wlezien’s initial study appeared in 2010. The following five years saw a period of extraordinarily rapid and far-reaching changes in the British party system. On the right, the populist UKIP collected a strong following from social conservatives, eurosceptics and elements of the lower middle classes and working classes. By the close of 2014, it had won the European parliament elections with 26.6 per cent of the vote, and two by-elections to the Westminster parliament.

The left was reshaped just as radically. The Scottish National Party had already demonstrated its strength in Scotland in 2011, when it won a supposedly impossible absolute majority in the Scottish parliament. The Scottish independence referendum of September 2014 produced a ‘No’ to its central question, but it also produced an extraordinarily mobilised ‘Yes’ campaign whose members swelled the SNP’s membership more than five times over. South of the border, the Green Party of England and Wales registered a strong surge in the polls, attracting left-liberal, middle-class voters who might have once backed the Liberal Democrats.

By this point, it was clear that the Liberal Democrats were polling badly (they scored only 6.6 per cent in the European elections). Obviously, much of this had to do with their poor tactical management of the coalition and their own public image. However, the growing polarisation in the British party system itself may have also played a factor.

In my earlier article, I noted that liberal parties tend to do well when certain of their rivals move to the extremes – specifically, conservative and social democratic parties. However, in another piece of research, published in the Australian Journal of Political Science, I found that overall levels of polarisation either have no effect on liberal parties, or tend to hurt them. That is, when the entire party system is polarised, with fringe parties waxing strong on the edges, the liberals tend to do badly. There may be several reasons for this: The fringe parties may pull away protest voters who might otherwise have picked the liberals for their small size and/or outsider status; polarisation may make centre parties less useful coalition partners; or polarisation may reflect social tensions that do not easily avail themselves of a centrist, consensual solution. In any case, it does not seem to do liberal parties any good.

Does this explain the Liberal Democrats’ failure? Probably not as much as the simple logic of the coalition, which forced them to make more concessions than the Conservatives did, and deprive them of the protest vote. But should this polarisation continue – and there is every indication that it will – it may well hamper any hope of a Liberal recovery, as attention drains away from them and their section of the political arena.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: Загружено CC BY-SA 2.0

Ben Margulies received a PhD in Government from the University of Essex in 2014. His thesis, titled “Liberal Parties and Party Systems,” examined the political competition of liberal political parties.

Ben Margulies received a PhD in Government from the University of Essex in 2014. His thesis, titled “Liberal Parties and Party Systems,” examined the political competition of liberal political parties.

Excellent piece. Post-election, I struggled with the seeming paradox of voters punishing the LibDems for coalition policies and rewarding the Tories. As you note, the Liberals had to give more ground and a polarised electorate had other alternative to them.