Unlike most EU states, Ireland uses a Single Transferable Vote system for its European Parliament elections. As Rory Costello writes, the nature of the electoral system ensures that campaigns tend to be dominated by individual candidates, rather than parties, with research suggesting only 35 per cent of Irish voters base their decision on a candidate’s party. As a result, the 2014 elections are unlikely to see the kind of swing toward Eurosceptic parties that may occur in other EU states.

Unlike most EU states, Ireland uses a Single Transferable Vote system for its European Parliament elections. As Rory Costello writes, the nature of the electoral system ensures that campaigns tend to be dominated by individual candidates, rather than parties, with research suggesting only 35 per cent of Irish voters base their decision on a candidate’s party. As a result, the 2014 elections are unlikely to see the kind of swing toward Eurosceptic parties that may occur in other EU states.

This article was originally published on the LSE’s EUROPP blog.

Much of the commentary on the upcoming European Parliament (EP) elections has focused on the potential gains for Eurosceptic parties. One would be forgiven for expecting a similar pattern to emerge in Ireland. It is the first EP election since the Irish ‘bail-out’ of 2010 and, during most of the intervening period, Irish economic policy was made under the close scrutiny of the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund (the troika).

While Ireland has now exited the bail-out programme, Irish voters have had to cope with a relentless programme of austerity over the past five years, and resentment towards the EU has grown. According to Eurobarometer figures, the percentage of people who view the EU negatively has more than doubled since the last EP elections (rising from 10 per cent in November 2008 to 23 per cent in November 2013). Equally, distrust of the EU has increased from 35 per cent to 55 per cent over the same period.

However, in contrast to other Member States that have had to endure severe austerity policies, such as Italy, no new credible Eurosceptic party has emerged that could realistically challenge one of Ireland’s 11 seats in the European Parliament. Indeed, the outcome of this election is unlikely to tell us much about Irish attitudes towards the EU or on matters of policy in general.

Importance of candidates

EP elections in Ireland are primarily about candidates rather than parties or policies. The electoral system used in the country, Single Transferable Vote, is more candidate-centred than the various list systems used in most other Member States. Voters can rank their preferred candidates from any party in order of preference – even on the ballot paper, candidates appear alphabetically rather than by party.

The emphasis on candidates is greater in EP elections than in national elections, primarily because the formation of a government is not at stake. Research from the Irish National Election Study suggests that around 65 per cent of voters make their choice in EP elections based on the candidate, with only 35 per cent choosing on the basis of party.

A party’s success in EP elections therefore depends to a great extent on the candidates they select. A candidate must be well known and be able to convey the impression that he/she will defend local interests in the EU. Parties often seek to ‘parachute in’ well known public figures to stand for them in EP elections. For example, in 2004 Fine Gael brought in television presenter Mairead McGuinness who went on to win a seat. In 2009 they recruited the former President of the Gaelic Athletic Association (the organising body for the national sports of Gaelic Football and Hurling), Sean Kelly, who also won a seat. The party has attempted to repeat this strategy this year by recruiting the former president of the Irish Farmers Association, but this effort thus far appears to have failed.

Because party labels are of secondary importance, high-profile candidates that are not a member of any party can do well in EP elections. Previous successful independent candidates include former Eurovision winner Dana Rosemary Scallon and Pat Cox, who went on to serve as President of the European Parliament. This year, two of the sitting Irish MEPs will contest the election as independents, and other high-profile independents may join the race.

Constituency changes

It is a mark of how far removed this election is from the major debates about the future direction of the EU that the most talked about issue so far has been the changes to the geographic constituencies in Ireland. To accommodate a reduction in the overall number of MEPs, the number of constituencies has been cut from four to three: one constituency for Dublin, and two large constituencies for the rest of the country.

To an outside observer, this might appear to be an irrelevant issue. After all, most Member States are not divided into constituencies at all for EP elections. Yet the redrawing of the constituencies has led to complaints about the difficulties of representing such large areas. This reflects a view that EP elections are about selecting delegates to defend local interests, as opposed to a mechanism for channelling citizens’ preferences on EU affairs.

Looked at in the round, this is a slightly odd perspective, given that local (or at least national) interests are already well represented in EU decision-making via the European Council and Council of Ministers. In contrast, there are no other elections in which voters have the opportunity to express their preferences on the direction the EU is taking.

Second order effects

The importance of candidate profile also means that the ‘second order’ election model has limited applicability in the Irish case. While government parties do tend to lose vote share, the outcome of the election in any given constituency depends primarily on the profile of the candidates. For example, the 2009 EP election came at a time when the ruling Fianna Fáil party were experiencing a dramatic decline in the polls.

Nevertheless, individual Fianna Fáil candidates managed to do very well in the election, such as the long-standing MEP Brian Crowley who topped the poll in his constituency. Overall, Fianna Fáil only lost one seat in 2009, and that was in a constituency that had one less seat available due to a reduction in the number of MEPs for Ireland. This is in sharp contrast to the results of the local government elections held on the same day, in which Fianna Fáil suffered significant losses.

Just as in 2009, the local government elections this year will provide a better barometer of the state of the parties than the EP elections held on the same day. Some ‘second order’ effects will, however, be evident in the EP election. Most noticeably, there is likely to be a swing away from the Labour Party (the junior partner in government, and a member of the Socialists & Democrats group), and Sinn Féin, a member of the GUE-NGL group, are likely to make strong gains.

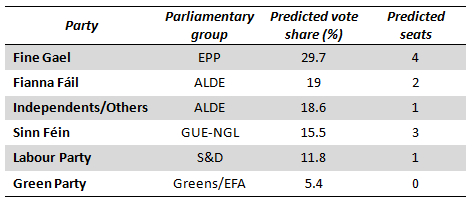

While Sinn Féin offer a more critical perspective on the EU than the Labour Party, one should be cautious in interpreting a swing towards them as a vote against the EU. Rather, it reflects voters’ assessments of the domestic performance of both parties, with Sinn Féin credited with a strong performance in opposition and Labour blamed for implementing cut-backs while in government. The Table below shows predicted vote shares and seats based on recent polling data.

Table: Predicted vote share and seats for 2014 European Parliament elections in Ireland

Note: Predictions are from Pollwatch2014 based on an average of polls from 22 February to 1 March.

Nothing to see here

Recent research on EP elections has pointed to the emergence of Europe-wide trends, as voters from across the EU respond in similar ways to common economic circumstances. The predicted gains for Social Democratic and Eurosceptic parties in May also suggest that the EP elections may be becoming more than simply 28 separate events. Ireland, however, is not the place to look for those who seek to detect pan-European trends. The elections are unlikely to tell us a great deal about Irish attitudes towards the EU or on matters of general policy. The only question that will be answered for certain here is: which candidates have won the popularity contest?

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

_________________________________

Rory Costello – University of Limerick

Rory Costello – University of Limerick

Rory Costello is Lecturer in the Department of Politics and Public Administration at the University of Limerick. His research interests include comparative European politics and the politics of the European Union, incorporating EU legislative decision-making, national and European elections, political representation and government performance.