Does geography play any part within a political party’s internal elections? As they build their Parliamentary careers, do potential party leaders develop a support base among other MPs representing the same region? Ron Johnston, David Manley, Charles Pattie, Hugh Pemberton and Mark Wickham-Jones have mapped where each of the candidates for Labour’s Leadership and Deputy Leadership in 2015 gained the necessary nominations to place them on the ballot papers and found some interesting patterns. Some of the candidates depended substantially on support from their ‘home region’, with one other the apparent beneficiary of local campaigning in another region by her team.

Ed Miliband’s resignation as leader of the Labour party in the immediate aftermath of the party’s general election defeat on 7 May, followed by Harriet Harman’s statement that she would step down as Deputy Leader immediately a new Leader was elected, initiated two contests to be undertaken under new rules adopted in 2014. In order to be on the ballot paper for either the Leadership or the Deputy Leadership, candidates have to be MPs and get at least 34 other MPs to nominate them – i.e. 15 per cent of the Parliamentary party (reduced to 232 by the general election). Thus there could be a maximum of six candidates for each post, assuming that all MPs were prepared to nominate one.

Four candidates declared early for the Leadership – Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper, Mary Creagh and Liz Kendall – with another, Chuka Umunna, withdrawing three days after announcing he would run; Tristram Hunt declined to stand after realising he could not attract sufficient nominations. They were joined in early June by Jeremy Corbyn, standing on an anti-austerity platform. Formal nominations opened on 10 June, and having received only ten nominations, Mary Creagh withdrew two days later. By the Monday morning when nominations were about to close, Corbyn had received barely half of the necessary 35 endorsements but in a frantic last session he managed to scrape sufficient (including four who initially endorsed Mary Creagh) with minutes to spare – including some who endorsed him in order to ensure that he was on the ballot despite not backing his policy positions. There was a similar scramble for endorsements two days later when nominations for the Deputy Leader closed with three of the candidates – Ben Bradshaw, Stella Creasy and Angela Eagle – only crossing the threshold at the last minute.

Many factors influence MPs in determining which candidate to nominate – or whether to nominate at all; 28 did not endorse any of the Leadership candidates, including the previous Leader (Ed Miliband) and his Deputy (Harriet Harman), plus the Chief Whip (Rosie Winterton) and all five of the candidates who made it on to the Deputy Leadership ballot (Ben Bradshaw, Stella Creasy, Angela Eagle, Caroline Flint and Tom Watson: Rushanara Ali, who withdrew from that contest at the last moment, had already nominated Jeremy Corbyn). Important factors influencing MPs’ choices are likely to include the candidates’ leadership potential – both for the party and, as a candidate for Prime Minister at the next election, for the country; their experience; their ideological position within the party; and their policies: as also were a number of personal issues, including such matters as (past and possible) portfolio assignments.

One other potentially significant factor is the location of the MP’s constituency relative to a candidate’s. In the 2010 Leadership contest, for example, Andy Burnham presented himself as the candidate from the Northwest with working class roots, opposed to the ‘Westminster elite’ who dominated the party and from which three of the other candidates were drawn (Ed Balls, David Miliband and Ed Miliband). Of the 33 MPs who nominated him then, 12 represented constituencies in the Northwest (mainly in Greater Manchester and Merseyside – he represents Leigh); in 2015 he got 68 nominations, 25 of them from his ‘home region’.

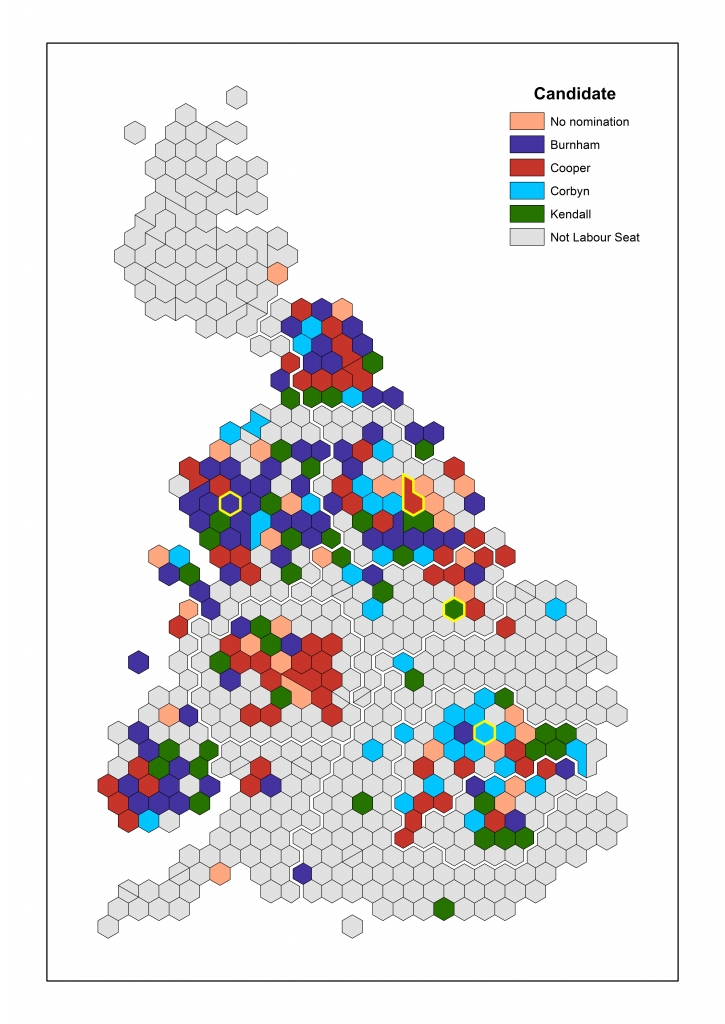

Burnham was not the only one of the 2015 candidates to get a substantial share of his support from neighbouring MPs. The first of the two cartograms (in which all Parliamentary constituencies have the same size, and the regional boundaries are indicated) shows the constituencies whose MPs nominated each of the four candidates. Outside the Northwest, Burnham performed well in the Northeast, Yorkshire & the Humber, and Wales, but not in the other regions with substantial Labour representation – the West Midlands and Greater London. The latter region, on the other hand, gave substantial support to its ‘local candidate’ – Jeremy Corbyn, MP for Islington North since 1983, was nominated by 16 of London’s 45 Labour MPs (six of whom didn’t nominate any candidate). Cooper and Kendall also both performed relatively well in London – with 10 and 9 nominations respectively – but neither performed particularly well in their ‘home region’. Cooper has represented Normanton, Pontefract & Castleford in Yorkshire (previously Pontefract & Castleford) since 1997, but gained only nine nominations (including her own) in that region. Kendall – an MP since 2010 only – represents Leicester South in the East Midlands: that region returned 14 Labour MPs in 2015, and she won nominations from only two of them.

One surprising feature of Cooper’s support base is the number of nominations she obtained in the West Midlands – 14 out of the total of 25. Shabana Mahmood – MP for Birmingham Ladywood – is involved in Cooper’s campaign, and was almost certainly influential in gaining her nominations from seven of the city’s nine Labour MPs; not only is she a Birmingham MP herself but her father had been chair of the Birmingham Labour party. (One Birmingham Labour MP – Gisela Stuart – nominated Kendall and the other – Roger Godsiff – did not nominate.)

****

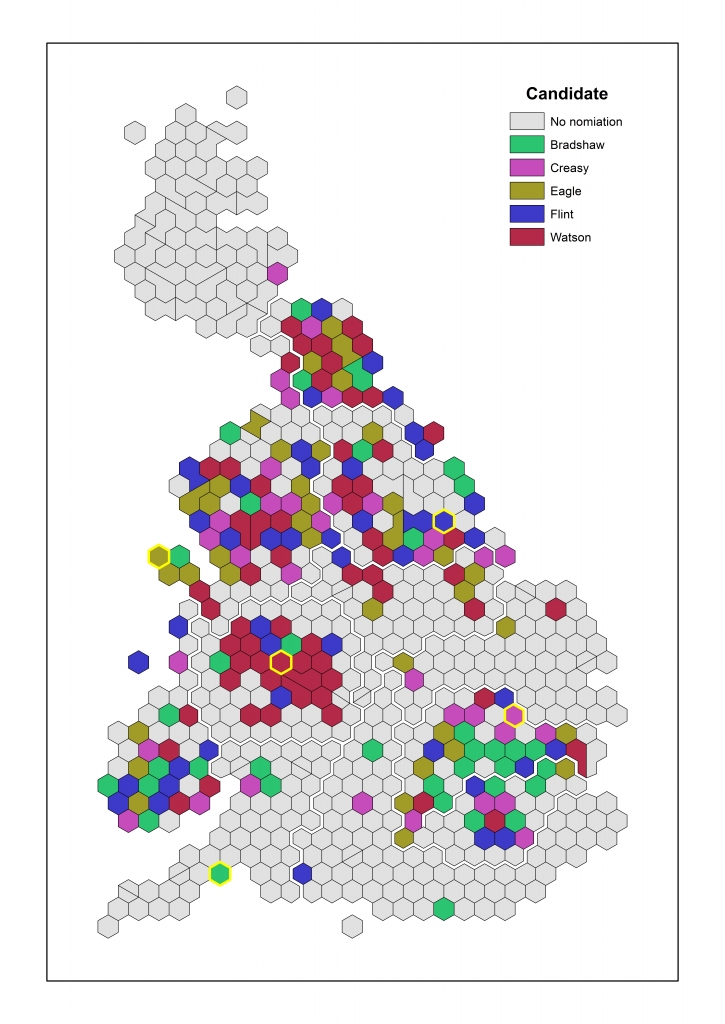

Turning to the contest for the Deputy Leadership, one of the clearest pictures to emerge from the second cartogram is Tom Watson’s dominance in the West Midlands – where he went to school and has represented West Bromwich East since 2001. That region returned 25 Labour MPs in 2015, of whom 19 nominated Watson, with Creasy and Eagle winning no support there at all.

None of the other candidates had such a geographic concentration of support among their fellow MPs. Angela Eagle represents a Merseyside constituency and she won nominations from eight local MPs, plus seven others from elsewhere in the Northwest region. Creasy, Flint and Watson also won several nominations from that region: Creasy got two nominations from Merseyside MPs, Flint from three, and Watson from one.

Creasy represents a London constituency – Walthamstow – but she was not the most popular choice there, getting nine nominations out of the 45 available compared to Bradshaw’s 14; she got 10 nominations in the Northwest. Bradshaw’s Exeter seat is one of only four in the Southwest region returning Labour MPs in 2015 – he won nominations from two of the others. He was also relatively popular among Welsh MPs, winning 6 of the 25 available nominations: eight others there supported Flint (there being no candidate for either position from among the Welsh Labour contingent).

****

Do these geographical patterns matter? Is where the Leadership and Deputy Leadership candidates got their nominations from likely to have any influence on how many votes they eventually get from party members? The final ballots in August and September will be ‘one person, one vote’ (in which individual members will be joined by affiliated supporters as well as registered who can pay £3 to affiliate with the party in order to participate in the election, without becoming full members). Labour party membership is not evenly distributed across the country. The most recent available data for all constituency Labour party memberships (albeit for 2010) show that one-fifth of all members lived in London and one-eighth in the Northwest region. Strong support for a candidate from MPs in those regions could be influential as some party members could well take account – either directly or indirectly – of who their own or a neighbouring constituency MP nominated (assuming that was a sincere nomination and not just a means of getting a candidate on the ballot paper); evidence from the 2010 leadership election clearly indicates that such ‘friends and neighbours’ voting was the case among constituency party members then. Thus, although Jeremy Corbyn and Ben Bradshaw are both considered outsiders in the Leadership and Deputy Leadership contests respectively, the number of endorsements they received from London MPs could mean that they perform better than expected overall because of support in the capital. Many of the endorsements were last-minute, however – 9 of Corbyn’s 16 and 6 of Bradshaw’s 14 – so the MPs involved (only six of whom endorsed both – they represent very different sections of opinion within the Labour party) may not do much to promote their cause during the campaigning months. Cooper’s and Kendall’s London nominations suggest they may perform well there too.

But will it matter? If a candidate’s support base is concentrated in a few parts of the country will this be a disadvantage compared to another who has attracted nominations from across most if not all regions and so has a more national base? (Labour, of course, has virtually no representation in the current House of Commons from some regions but has many members there – the Southeast of England is home to 11 per cent of all Labour party members but returned only 4 MPs in 2015; Scotland has 7 per cent of the membership and one MP! For whom will those members vote?) Only time will tell, but that there are geographies to some candidates’ support among their colleagues is an interesting initial indicator of where their electoral strengths and weaknesses may be.

About the Authors

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol. Ron’s academic work has focused on political geography (especially electoral studies), urban geography, and the history of human geography.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol. Ron’s academic work has focused on political geography (especially electoral studies), urban geography, and the history of human geography.

David Manley is a Lecturer in the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol.

David Manley is a Lecturer in the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol.

Charles Pattie is Professor of Geography at the University of Sheffield, specialising in electoral geography.

Hugh Pemberton is Reader in Contemporary British History at the University of Bristol.

Hugh Pemberton is Reader in Contemporary British History at the University of Bristol.

Mark Wickham-Jones is Professor of Political Science at the University of Bristol.

Mark Wickham-Jones is Professor of Political Science at the University of Bristol.

You may be interested in a short post I wrote on the impact of endorsement in the 2010 leadership election: http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2015/06/why-labour-mps-could-still-decide-final-result