Drawing on new polling of attitudes to Brexit, Marley Morris explores the public’s preference for different trade scenarios when faced with a number of difficult trade-offs. He concludes that, if the government wants public support for its negotiating position, it must negotiate a deal that keeps the European model close – and rejects the deregulation agenda.

Drawing on new polling of attitudes to Brexit, Marley Morris explores the public’s preference for different trade scenarios when faced with a number of difficult trade-offs. He concludes that, if the government wants public support for its negotiating position, it must negotiate a deal that keeps the European model close – and rejects the deregulation agenda.

The strange irony of Brexit is that the origins of the movement for withdrawing from the EU in the 1990s and 2000s have little in common with the public’s own motivations for voting Leave in 2016. The earlier campaigns for leaving the EU were at heart free-market and libertarian: they argued that the UK should break free from the protectionist shackles of EU institutions, set alight a bonfire of EU regulations, and forge new trade deals around the world. But, as we find in IPPR’s latest research, the public’s vision of Brexit is rather different. As the next stage of the UK-EU negotiations begin – on the all-important question of the future partnership – and the government is forced to confront some seemingly intractable trade-offs, it is essential to understand where the public’s priorities for the negotiations really lie.

With the help of polling company Opinium, we tested how the public would navigate a series of binary trade-offs in the negotiations – on trade and regulations, on immigration and services, on the ‘level playing field’ and state aid – to get a clearer view of their vision for post-Brexit Britain. The picture that emerged is in stark contrast to how the earlier generation of Brexiteers originally envisaged life outside the EU.

First, on regulations, we found that the public consistently favoured high employment, consumer, and environmental standards. For many of the policies which UK governments opposed at the time of their introduction and which were the cornerstone of earlier Euroscepticism – the Working Time Directive, the cap on bankers’ bonuses, renewable energy targets – we found firm public support. There was no appetite for deregulation among either remainers or leavers, and in some cases – such as the cap on bankers’ bonuses – both sides wanted tougher laws than already exist.

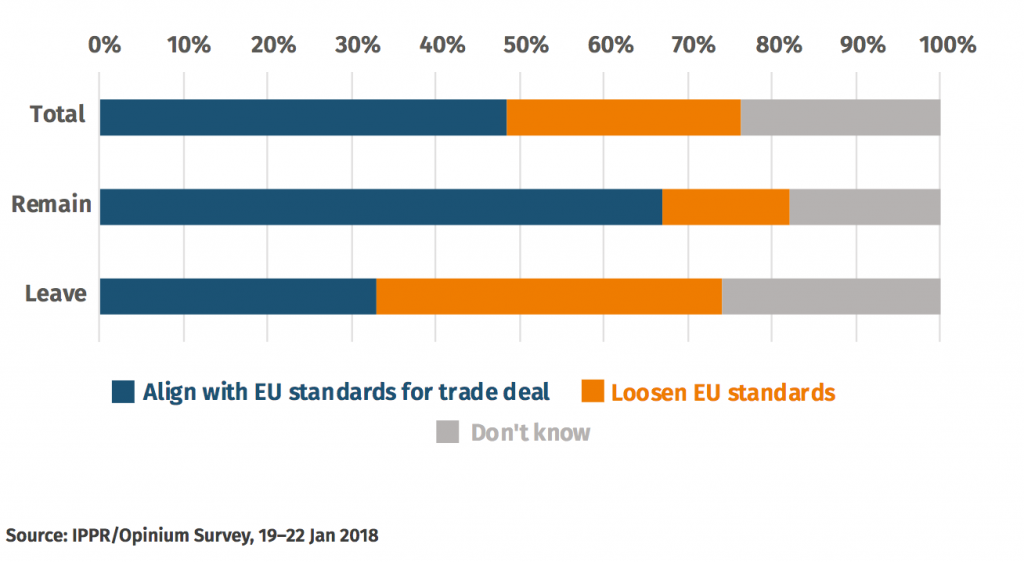

Figure 1: the public favour continued alignment with EU standards over deregulation

We also asked the public about the EU’s call for there to be a ‘level playing field’ between the UK and the EU post-Brexit, which includes requirements on aligning regulation and state aid rules. When asked whether they would prefer to align with EU consumer, environmental and employment rules to secure a far-reaching UK-EU trade agreement or instead lower standards, the public backed alignment (49%) over deregulation (28%).

On the other hand, the public showed considerably greater interest in a more activist state aid policy: when asked whether they would prefer to have greater flexibility on state aid to protect particular industries or to keep state aid limits for a far-reaching EU trade deal, 53% favoured greater state aid flexibility over EU state aid limits. On free movement, too, when asked to choose between imposing controls on EU citizens or maintaining free trade in services, our respondents showed a stronger preference for restricting immigration than for protecting services trade. The public seem more interested in using Brexit to enhance the power of the state than to roll it back.

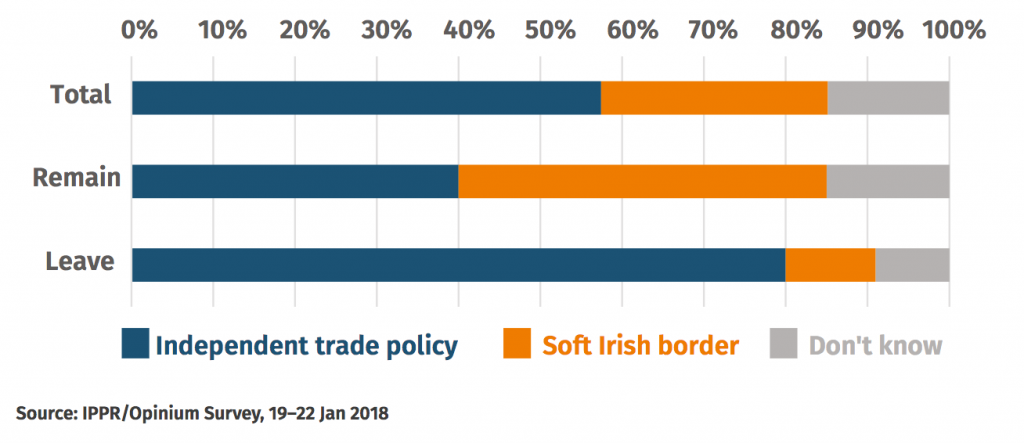

Even on future trade deals, the public are not instinctive free-trading libertarians. While in principle the public have a clear preference for an independent trade policy – more people favour this than favour maintaining a soft Irish border – in practice there is strong opposition to any free trade agreements that lead to a race to the bottom.

Figure 2: there is a public preference for having an independent trade policy over protecting the soft Irish border.

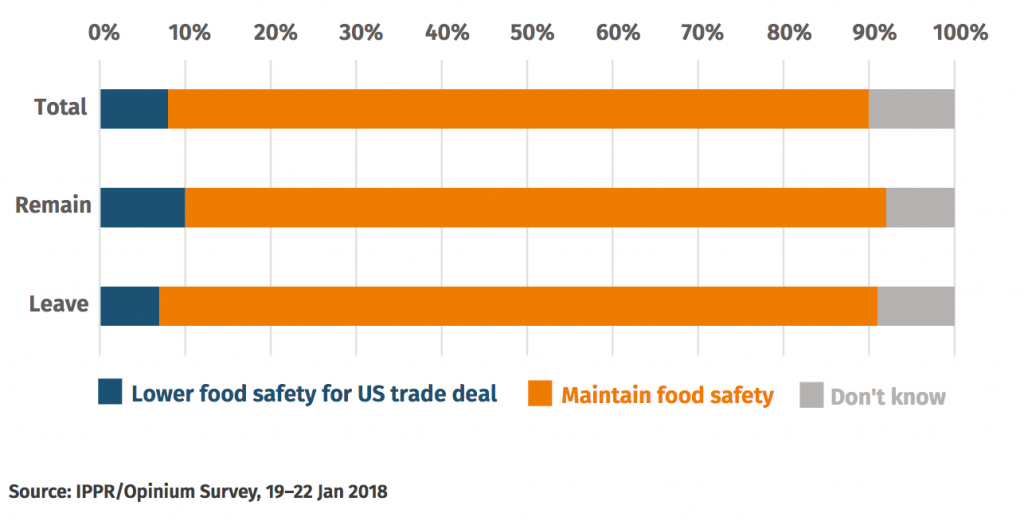

US commerce secretary Wilbur Ross has suggested that alignment on food safety standards would be central to any future UK-US trade deal, but our survey found that only 8% of the public supported deregulating food safety standards in return for a trade deal with the US, compared to 82% who supported maintaining current food safety standards. Negotiating trade deals around the world may well turn out to be even more politically controversial than our membership of the EU.

Figure 3: the vast majority of the public are unwilling to sacrifice maintaining food safety standards for a trade deal with the US.

The vote to leave the EU was therefore far from a call for the UK to become a buccaneering, deregulated Singapore-on-Thames; instead the public appear to expect a larger state post-Brexit, with tougher regulations on everything from environmental protections to financial policy, additional controls on immigration, and more opportunities to use state aid. The referendum was more a vote for re-regulation than for de-regulation.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that all hope is lost in the negotiations. There are models that can address the public’s priorities while protecting our economy – for instance, IPPR’s ‘shared market’ approach, which prioritises continued alignment with EU rules while allowing for the option to diverge over time.

But it does mean there is no public appetite for a rupture from the European economic and social model after Brexit. There are signs that some parts of the government recognise this: Brexit Secretary David Davis has dismissed suggestions that withdrawal will be a means of cutting loose EU regulations, while DEFRA Secretary Michael Gove has pursued a high-standards agenda in environmental policy. Yet this will mean nothing without the right deal. As the next stage of talks with the EU begin, if the government wants public support for its negotiating position it must put its money where its mouth is, and negotiate a deal that keeps the European model close – and rejects the deregulation agenda outright.

_________

Note: the above draws on an IPPR briefing, available here.

Marley Morris is Senior Research Fellow at IPPR.

Marley Morris is Senior Research Fellow at IPPR.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

@Mike, saying “building new standards to secure a trade deal with US” (or Australia just the same) is much more biased than the actual question! You can’t call “building new standards” a replacement of the EU full watch all along the breeding process by a simple chlorine shower at the end of the process, Calling that “loosening EU standards” is already put very mildly. Same for acid-washed/ ractopamine-treated pork, or growth hormone-injected beef. In terms of bias, I find this study very neutral as it sticks to the government’s statements without assuming that a trade deal with the US, especially “comprehensive”, could also have other dire consequences on environmental standards (ex.shale gas fracking in northern England by US companies) or even social standards (NHS hospitals management devolved to US companies). Let alone the expectable pressure put on the UK government to ignore the independance of the BoE and have an hawkish monetary policy, that would make US products much more affordable to British public – but at the full expense of British producers. You’re free to find anti-Brexit bias everywhere and even to throw some dead haddock in the Thames in protest, But this study is not biased against Brexit, indeed it’s a very mild and consensual study if you ask me.

Its unfortunate that any poll on anything brexit related is incapable of asking unbiased questions. “Loosen EU standards” rather than “Create and follow UK standards” and “Lower food safety for US trade deal” instead of “Create own food regulations to improve chances of negotiating trade deal”.

The bias in the questions ensures the response seen. They state to the respondent that they would be choosing lower and less safe standards rather than different ones. This is bread and butter to a polling company so the intended bias is deliberate. Wouldn’t we all be better informed if polling was used to find out public opinion rather than pre arrange a result to assist in a campaign?

You miss the point that the EU is not actually a ‘free market’ but a highly regualted system of controls of innovation, market entry, anti-competition, unfair consumer activities, especially in restrictive choices and over-pricing. The ‘Single Market’ regime is protectionist by these mechanisms and if this does not stop non-EU products entering then the Customs Union CET is there to dissuade sales and feather the Brussels nest of useless expendiures. This is why the UK exports and Imports more goods and services with non-EU members and why the EU itself is a declining portion of the world economy.

But of course the author believes that the Single Market is something like a Super Shopping Mall.

There has always been a lurking disjunction between the promises of the Brexit campaign and the reality of its delivery. The British people did indeed vote for deregulation, but the deregulation they voted for was the bendiness of bananas and the usage of tea bags. The reliance of the Brexit campaign upon a parody of EU regulatory imposition was always going to hit a wall when it came to deregulation itself eating into areas the public would find unacceptable. One of the first areas slated for deregulation was the construction industry, but Grenfell put paid to that.

We’re going to see many such disjunctions now. We’re already seeing several of them in the course of negotiations with the EU. Brexit was always a short-term project. Get the vote in for leave by any means possible, worry about what to do with it later.

Brexiteers must be to blame for everything, but it would make more sense to blame the EU for the Grenfell disaster. After all, Bruxelles is monitoring, controlling and overseeing everything, and, more to the point, there is no limit to its self-instituted remit. Everything is under the watchful eye of the EU Commissariat, except the plebeian EU Claytons citizen people are appraised of the entire program piecemeal, because the plebs would not swallow the whole dictatorship acquis communautaire hogwash all at once.

This is a very eat-your-cake-and-have-it comment. Extending the contention, anything that’s gone wrong in the UK since 1973 is the fault of the European project because it exercised insufficient oversight and control over the British government and British standards. Thus a vote for Brexit is justified on the grounds the EU has permitted us too much independence.

I honestly feel that some Brexiteers get up in the morning, find they forgot to get the milk in for their morning cuppa, and shout ‘Damn those Europeans!’ as a purely instinctive response, continuing to do so for the rest of the day every time something goes wrong. What next? If Brussels only policed us better there’d be fewer murders on London’s streets? We have to leave the EU because our PM is still British and thus bound to screw up?

We must leave the EU because we’re incapable of looking after ourselves without their assistance and they’re not exercising sufficient control has to be the weirdest contention I’ve yet come across and, when it comes to the contentions of Brexiteers, I’ve heard some weird ones.