While politicians of all stripes talk about the need to build more homes, very little detail has been unveiled for how they will actually be built, writes Andrew Carter. A new report by the Centre for Cities details three necessary components: the density of housing within existing city boundaries needs to be increased; some parts of greenbelts need to be built on; and neighbouring authorities surrounding the nation’s most high-demand cities need to coordinate better in order to develop sites.

While politicians of all stripes talk about the need to build more homes, very little detail has been unveiled for how they will actually be built, writes Andrew Carter. A new report by the Centre for Cities details three necessary components: the density of housing within existing city boundaries needs to be increased; some parts of greenbelts need to be built on; and neighbouring authorities surrounding the nation’s most high-demand cities need to coordinate better in order to develop sites.

It is encouraging that there is now broad agreement amongst politicians, academics and policy commentators that the UK needs to build more homes. But unless we see dramatic changes to housing policy, the minimum target of building 200,000 new homes per year is unlikely to be achieved. This is because, while national politicians play the numbers game vying for larger targets or more dramatic rhetoric, there remains little detail as to where these homes will actually be built. Moreover, the fact remains that we simply will never solve the housing crisis while some of the most sensible solutions from both a policy-making or economic perspective have been taken entirely off the table.

Looking at the UK’s housing market, it’s clear that demand for new homes is much greater where the economy is strongest, and that at the same time, our most successful cities tend to be least affordable. For example, housing in Oxford is around fifteen times local incomes, whereas in Stoke it’s more like five times the value of incomes. That’s because new house building has failed to match either the scale or the geography of this demand. For example, between 2008 and 2013 there were relatively more homes built in Barnsley – the second most affordable city in Britain in which to buy a house given local incomes – than in London or Oxford, the least affordable cities.

But failing to build the homes that the most successful cities need risks significantly constraining their growth, as well as that of the national economy. In too many of these cities, residents are being priced out of labour markets, meaning businesses are struggling to attract the right talent and experiencing lower consumer demand. While there is no silver bullet solution to meeting the demand for new houses, at the heart of any response needs to be the issue of land supply, as the only way to build more homes in the country’s most successful cities is to increase the amount of land allocated for housing.

Centre for Cities’ latest report sets out the three necessary components of an effective policy response to this challenge:

The first step is to increase the density of housing within existing city boundaries, through identifying and developing brownfield land. In the UK’s ten least affordable cities alone, there is the capacity for around 425,000 extra houses on brownfield land. In Reading, for example, there is the capacity for around 8,440 more homes. Given the complexities of developing many of these sites, however, the report calls on national Government to support and enable cities to capitalise on these opportunities. The reality is that this will require significant investment which, in the current political climate, may be difficult to secure.

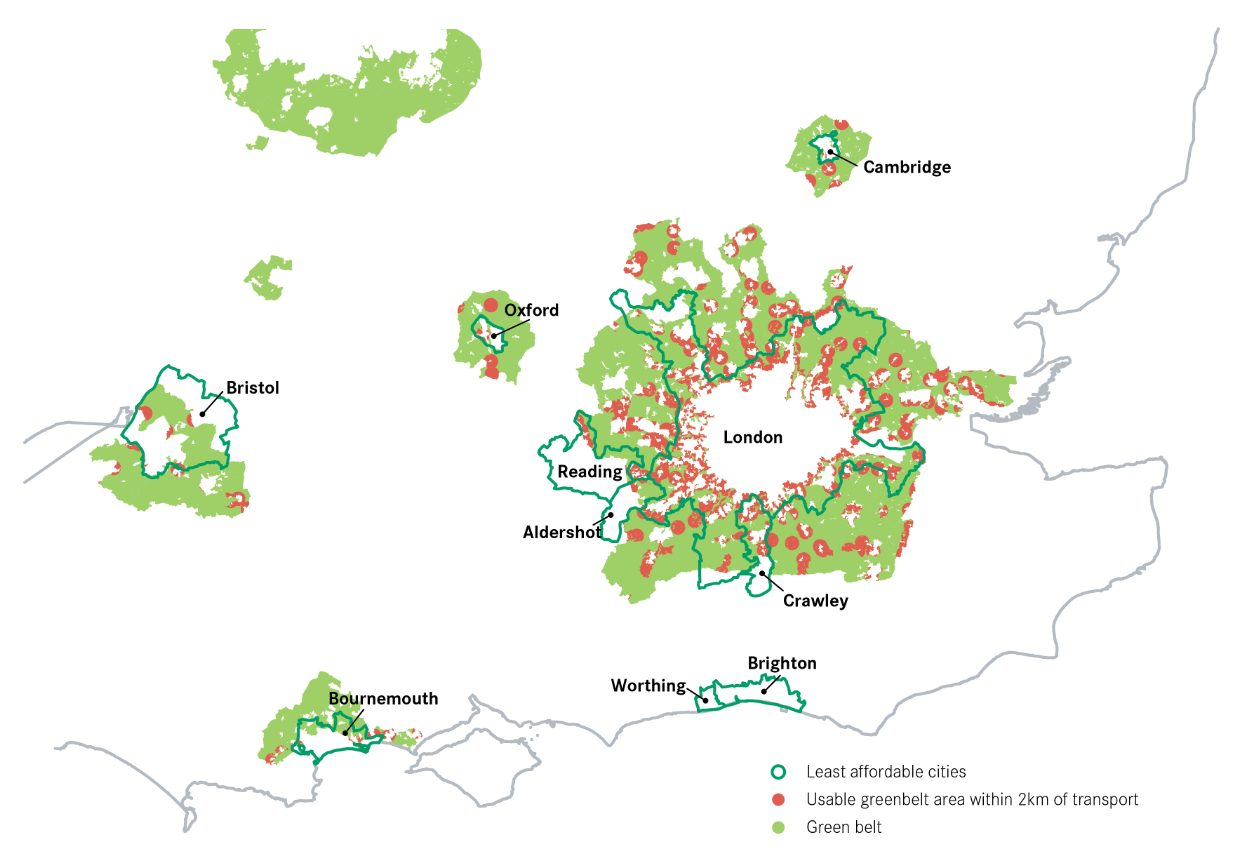

However, brownfield land alone will not meet the housing needs of the UK’s most successful cities, over the long term – indeed, the 425,000 homes it offers could only deliver two years’ national target. This is why the second necessary response to build the homes needed in these cities must involve evaluating land on its merits rather than its existing designation. For example, within a 25 minute walk of a train station there exists land for a potential 1.4 million homes inside the ten least affordable cities’ existing built-up areas – on land currently designated as greenbelt. Contrary to popular belief, doing so would not require cities to “concrete over” their surrounding green spaces – even if all 1.4 million homes were built on these sites, 95% of these cities’ current greenbelt areas would remain intact, and because greenbelt land is so plentiful, only the least attractive sites would need to be prioritised.

Greenbelt areas close to transport

Source: DCLG 2007, Greenbelt geographical extents provided by English Local Authorities. Contains Ordinance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database right 2014 and Environment Agency Data.

Because housing markets for successful cities extend well beyond their own administrative areas, the third essential component to deliver long-term supply in the UK is to encourage cities to work much more closely with their neighbouring authorities. Around half of urban workers live and work in different local authorities – often travelling from homes in surrounding areas to jobs in the city centre, which is why housing and infrastructure provision is most effectively delivered at the true scale of the local economy. If the neighbouring authorities surrounding the nation’s most high-demand cities worked together to develop sites close to train stations, there would be enough land for 3.4 million homes, on just 12.5 per cent of these cities’ greenbelt areas.

Each of these steps require cities to consider where opportunities match with existing infrastructure, and how best to link new homes to the jobs and services that offer people the most opportunities and make these cities successful. But critically, as has so often been the case in political debate, none should be off the table – including the greenbelt. Cities must be bold in identifying accessible land for more homes, and national politicians must support them in doing this. Otherwise, regardless of policy announcements and ambitious targets, the homes these cities, and the national economy, so desperately need, will continue to go unbuilt.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Andrew Carter is Acting Chief Executive of the Centre for Cities. He can be found on Twitter @AndrewCities.

Andrew Carter is Acting Chief Executive of the Centre for Cities. He can be found on Twitter @AndrewCities.

You correctly point out that the UK as a whole isn’t short of homes, it is just that the centres of economic wealth – and in particular London – do not have enough residential properties to match demand.

That is the simple reason why property in London is so much more expensive than the rest of the UK. Fulham estate agent http://lawsonsanddaughters.com/ recently said the average price of a home in Hammersmith has risen above £1m. And it will continue rising until other parts of the UK rival London’s economic dominance.

Planning controls have made development land a scarce resource which in turn has driven up the price of land and ultimately the price of housing. Perhaps we need to look at introducing a system adopted in some parts of europe whereby the price of development land is controlled which is then reflected in the prices/ rental that residents pay for the property. I spent some time working in the German planning system which used a very powerful planning tool, the “Bebauungsplan” – this was effectively a statutory development brief required for most development sites and set out the amount of development which could be built almost to the last sq.m and, by consequence, the value of the land. Interestingly the “Bebauungsplan” also dictates that a green strategy, or Green Plan has to be undertaken for the development site ensuring that the ecological value of each site is retained and improved. I sometimes feel that we should be looking more closely at what some european countries are doing in planning terms to see what lessons can be learnt and what may be tranferable to the UK.

The perceived need for more houses should be considered against the housing and population statistics.

In the UK we have more houses per head of population in 2012 than we did in 2002.

Perhaps we should tackle the geographically skewed nature of our economy rather than trying to make a bad situation more comfortable.

The high salaries paid to top employees and the protection of asset values by the QE policy is distorting the economy, housing demand and house prices in London and the south east.

Family units have got smaller. Perhaps we haven’t faced up to the fact that living alone is more expensive, and we can’t all afford it.

Perhaps ‘need’ has got confused with ‘want’, and the benefits of a short term building boom are driving policy.

Perhaps part of the answer is to reduce the very highest salaries and thus the difference between higher paid employees and the average.

Bring in a Mansion Tax or Higher bands Council Tax.

Distribute the productive economy more widely across the country.

Yes, use brownfield land, and build near train stations. But don’t destroy the green spaces and our ecological, agricultural and landscape assets.

Perhaps it will take more than a three point policy.