LGBTQ+ drug users lie at the intersection of (at least) two structurally marginalised communities. To ensure the provision of the most effective information, interventions and services for LGBTQ+ people who use drugs, argues Jay Jackson, we urgently need to improve our understanding of drug use among this group.

February is LGBT+ History Month, and the histories of modern drug use and of queerness are woven intimately together. LGBTQ+ people have historically been “early adopters” of “club drugs” such as MDMA and legal highs like mephedrone, with gay men and trans women in particular pioneering the development of dance music and nightlife in cities like New York, San Francisco and London during the social and political turbulence of the 1970s and ‘80s.

It is, however, crucial to avoid using discussions of LGBTQ+ drug use to stigmatise, stereotype or pathologise people from this community, or to sensationalise or fetishise the issue. While rates of drug use among LGBTQ+ people appear to be significantly higher than they are in the general population, the majority do not use illicit substances. Among those who do, the vast majority do so in ways which are not associated with significant harms. LGBTQ+ drug use is more likely to be a response to trauma and harms, than the cause of them.

It is crucial to avoid using discussions of LGBTQ+ drug use to stigmatise, stereotype or pathologise people from this community.

What we know

From the limited data available, we can be pretty confident that LGBTQ+ people use drugs at higher rates than straight people – even when controlling for gender and age – but the data on specific groups within the community is either patchy or non-existent.

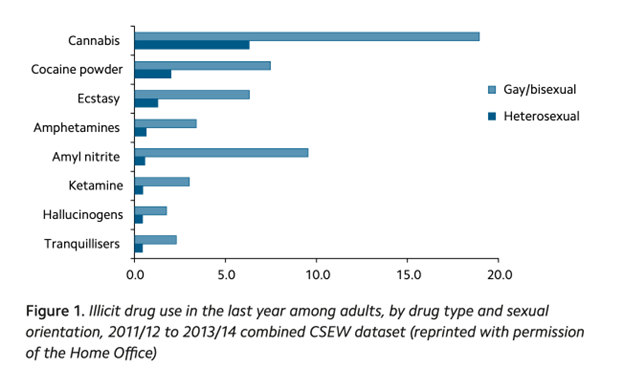

Within the LGBTQ+ community, rates of drug use are highest among men who have sex with men (MSM), whilst women who have sex with women have also been shown to have higher levels of drug use than their heterosexual counterparts. Gay men report higher overall rates of drug use than lesbian women, largely due to higher rates of stimulant use, particularly amyl nitrites – better known as “poppers”. The vast majority of studies conducted to date focus on MSM, so research on lesbian and bisexual women is very limited, and almost nothing has been written about trans people.

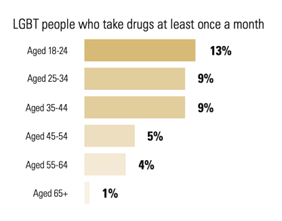

The latest available data suggests that 2.6 per cent of all adults aged 16 to 59 years in England and Wales have taken any drug once a month or more in the last year. The equivalent figure for LGBT people in a 2018 Stonewall report was 9 per cent – over three times as many.

Existing research also indicates that the rate of substance abuse disorders among LGBTQ+ individuals – while not precisely known – may be as high as 20 to 30 per cent, which is significantly more common than in the general population (9 per cent). This was attributed to factors such as the ubiquitous availability of substances within LGBTQ+ social settings, internalised stigma and expectations of rejection, and use as a way of coping with interpersonal and structural discrimination.

What we don’t know

Fundamentally, we are yet to gain a full understanding of the reasons why LGBTQ+ people use drugs at elevated rates compared to the general population. Clearly, there will not be any single cause, a myriad of factors will inform these trends, likely including but certainly not limited to: coping mechanisms, sexual enhancement and experimentation, self-actualisation, identity formation, community bonding and, simply, indulgence and enjoyment.

Research that recognises, respects and accounts for different LGBTQ+ identities and pursues lines of enquiry based on the lived experience of queer people would greatly enhance our understanding of intra-community differences in drug use, and provide a more authentic, useful picture.

One example of the variety of reasons behind drug use across the LGBTQ+ spectrum is the very specific use of hallucinogens and/or ecstasy by trans people for gender-affirming sexual experiences. More research needs to be devoted to trans drug use in particular to help support and affirm trans people, in light of the attacks on their rights that they currently face.

Effective policies for better outcomes require meaningful engagement

Better understanding of the extent and nature of LGBTQ+ drug use would present health bodies, local authorities and drug policy campaigners with more effective opportunities to tailor interventions to the community. Ensuring all national datasets on illegal substance use include analysis by sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as accounting for people with multiple protected characteristics (such as LGBTQ+, disabled or BAME people) would be a useful start.

The commissioning and accessible provision of specific services for LGBTQ+ people based on needs and issues identified is also crucial. These should be situated in convenient places – such as Birmingham’s LGBT Centre which is just on the edge of the Gay Village – and offer a variety of services under one roof (eg, sexual health services, counselling, hate crime reporting and domestic violence refuge as well as drugs/alcohol harm reduction information, equipment and support).

More fundamentally, a total reassessment of our approach to drug laws is required. Recent decades have seen a sharp rise in the number of new drugs that are controlled through the Misuse of Drugs Act (culminating in the 2016 Novel Psychoactive Substances Act which criminalises all existing and yet to be invented psychoactive substances not already controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act). This has the potential to disproportionately criminalise and thus further stigmatise LGBTQ+ people because of their greater use and early adoption of new substances.

Add to this recent failed attempts to outlaw poppers and the reclassification of GHB and its related substances – popular in MSM chemsex communities and likely used almost exclusively by queer people – and it is clear that gay people are at significant risk of overcriminalisation, particularly given the continued presence of homophobia in the police.

Drug policy reform and the LGBTQ+ liberation go hand in hand

Other policy interventions that could and should be carried out within the current legal framework to ensure that LGBTQ+ people who use drugs aren’t being put at unnecessary risk include better dissemination of harm reduction information in gay night-time economy venues, festivals and Pride events to ensure that people who do choose to take drugs are doing so as safely as possible.

Additionally, health and social care professionals should be better trained to identify and care for the wellbeing and mental health needs of LGBTQ+ people, who are often made to feel invisible within national health systems. Recent government pushback on the implementation of exactly such measures does not bode well.

The drug policy reform movement and the LGBTQ+ liberation movement are both natural allies and necessary companions.

There is still much to learn about LGBTQ+ drug use, and it’s imperative that we fill the gaps. The higher numbers related to drug use and abuse “indicate a need that hasn’t yet been met”. The drug policy reform movement and the LGBTQ+ liberation movement are both natural allies and necessary companions. Given the outsized impact of our “war on drugs” on LGBTQ+ people, it’s vital that we shift to an approach based on knowledge, understanding and listening. The only way to better understand queer drug use is by listening to the voices of queer people themselves.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Photo by Alexander Grey via Pexels.