It is a mistake, committed by many, to equate a substantial SNP vote with an alleged rise in nationalism or nationalist sentiment in Scotland, argues Jan Eichhorn. The evidence indicates the contrary: data from the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey suggests that fewer people emphasise their Scottish national identity distinctively.

It is a mistake, committed by many, to equate a substantial SNP vote with an alleged rise in nationalism or nationalist sentiment in Scotland, argues Jan Eichhorn. The evidence indicates the contrary: data from the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey suggests that fewer people emphasise their Scottish national identity distinctively.

The 2015 general election will be memorable for many reasons, a key one being the remarkable victory of the SNP gaining 56 of 59 seats in Scotland (increasing their share dramatically from just 6 seats in 2010). Naturally, such a landslide attracts the focus of journalists, commentators and politicians who aim to assess the outcome of the election. Since the exit polls closed a lot of people have tried to make sense of what happened in Scotland. Unfortunately a lot of them made statements that have to be rejected as simply inaccurate.

It is a mistake, committed by many, to equate a substantial SNP vote with an alleged rise in nationalism or nationalist sentiment in Scotland. It may seem a plausible assumption to engage with (if you do not understand the attitudes of the Scottish electorate), but it cannot be supported by any empirical evidence. To the contrary: the best evidence we have to give us a long term perspective, data from the high-quality, face-to-face Scottish Social Attitudes Survey (SSA) suggests that, if anything, fewer people than before emphasise their Scottish national identity distinctively.

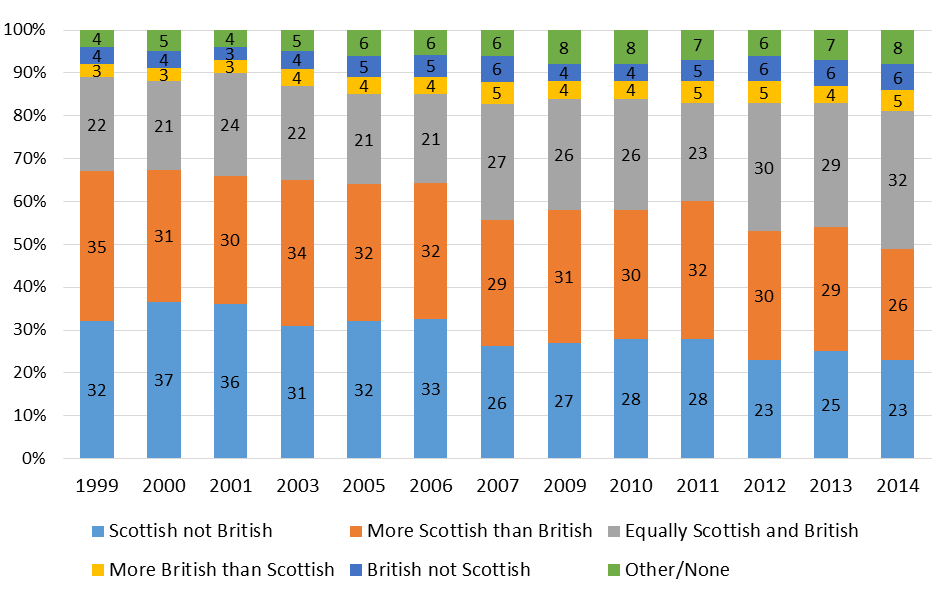

The figure below summarises how people in Scotland weigh their Scottish identity in comparison to their British identity. They have not become un-Scottish since the opening of the Scottish Parliament in 1999: The proportion of people in Scotland that says they identify as more British than Scottish or British only remains small at just over 10 per cent. However, at the other end of spectrum we have seen some quite substantial change.

Figure 1: Scottish and British National Identity in Scotland, SSA 1999-2014

Until 2006 each year around two thirds of respondents said that they felt more Scottish than British or Scottish and not British at all. At the same time, only just over one in five rated their Scottishness equally to their Britishness. This has changed with the numbers of those not favouring one identity over the other increasing since the SNP began to form the government in Scotland following the Scottish Parliament elections of 2007. In the year of the independence referendum, nearly one third of respondents fell into this middle group, while those singularly identifying as Scottish only had dropped from over a third in the early years of devolution to just under a quarter.

To just make the point absolutely clear: Scottish identity or sentiment has not been increasing, but decreasing gradually since the advent of devolution. There has not been a higher relative level of emphasising Britishness in Scotland than in the year when the referendum on its independence was held.

To those who study Scottish political attitudes that is not a surprise. In 2011, when the Scottish Parliament elections saw the SNP get an absolute majority of seats (with around 45 per cent of the vote), support for independence was at the lowest level recorded by the SSA with just one in four Scots supporting it. Amongst those who voted SNP, over 40 per cent were not in favour of independence at the time. While support for independence has grown of course since (and reached 45 per cent in last year’s referendum), this tells us an important message about SNP support: The SNP has not gained voters because it could increase the feeling of national identity, but has done so for other reasons. And in this general election they were able to translate the 2011 support from Scotland to the UK level (and gain some additional votes).

Crucially, commentators need to stop painting a picture in which the majority of Scotland predominantly base their political decision making mostly on their national identity. There has been no rise in nationalistic sentiment in Scotland. As we (amongst others) have repeatedly shown in our research, the strongest determinants of both independence and SNP support were pragmatic evaluations about economic prospects, trustworthiness and political personnel. For most people in Scotland the SNP is a normal party, that they like, hate or are indifferent to, but those evaluations for most are based on whether people agree with their policies and how they evaluate their representation.

If commentators want to understand why the SNP is successful, they need to make a greater effort at properly understanding how public attitudes are formed in Scotland. Suggesting that it is down to sentiment is lazy at best, but actually misrepresenting the majority of Scottish voters. For political parties trying to challenge the SNP, first and foremost Scottish Labour, a similar message applies: to have a chance of engaging them successfully, they need to stop focusing mostly on high-level questions about different types of nationality. Instead they need to challenge the SNP on concrete policy debates around issues that affect people’s lives and which voters in Scotland are much more likely to base their votes on than identity-driven arguments.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Jan Eichhorn is Chancellor’s Fellow (Social Policy) at the University of Edinburgh. He tweets from @eichhorn_jan.

Jan Eichhorn is Chancellor’s Fellow (Social Policy) at the University of Edinburgh. He tweets from @eichhorn_jan.

During the years of conventional Westminster government, Scotland lost railway lines and got secondary infrastructure, such as Scottish Motorways, to the former Scottish Development Department specification, basically dual carriageways with blue signage.

There can be no doubt that since devolution and especially since the SNP took office, that there is now a renewed positivism towards meaningful development.

The unionist politicians can be ethnicity Scottish but unless they actively pursue the Scottish narrative, then they will be seen by an increasingly well informed electorate as Westminster tools.

The process under way is not about having Scottish grannies. It is about the enrichment and reconstruction of Scotland, for all who live there.

From the 2011 census:

62 per cent of the total population stated their identity was ‘Scottish only’. That proportion varied from 71 per cent for 10 to 14 year olds to 57 per cent for 30 to 34 year olds.

The second most common response was ‘Scottish and British identities only’, at 18 per cent. This was highest in the 65 to 74 age group, at 25 per cent.

‘British identity only’ was chosen by 8 per cent of the population. The highest proportion stating this identity was the 50 to 64 age group (10 per cent).

‘Other identity only’ represented 4 per cent of the population. The proportion was highest in the 20 to 24 (11 per cent), 25 to 29 (13 per cent) and 30 to 34 (11 per cent) age groups.

This article seems to be more wishful thinking that factual. For several decades support for Scots independence stood at 33-35 per cent, a subject I studied deeply. The British establishment preferred to concentrate on one poll that showed only 29%. In the referendum 45% of folk voted for independence (the biggest attitude survey ever held in Scotland)

Of course, about 10% of the population of Scotland have come from south of the border. Most of them are “British not Scottish.” Many support Scottish self-determination and some campaign for it, which is this article’s main mistake. Self-determination doesn’t entirely equate to national identity.

Add to that the increased immigration to Scotland from particularly Eastern Europe in recent years. Of course they are neither Scottish nor British. No great surprise there. Brits living on the Costas’ aren’t Spanish or Catalan!

The fact is that not only has support for the SNP substantially increased in recent years but support for self determination has as well.

I do welcome such complacency though!

An interesting article and it echoes my own thoughts around the SNP Westminster landslide not necessarily reflecting a massive increase in separatist sentiment.

However in all this talk of nationalism, there is another, equally potent one, which is never discussed. British nationalism. Most readers of this post and btl commenters are British nationalists. People are so marinaded in British nationalist propaganda from birth they don’t even realis. the fact. But ask yourself this. If nationalism is defined as opposition to or hatred of something, do you oppose or hate independence or the SNP? Welcome to the world of nationalism – British style.

“If nationalism is defined as opposition to or hatred of something”

It isn’t.

With regard to another referendum, we don’t need one – we just had one. The result was a clear win for the no camp. We are a unionist country. The SNP will have to find some way to fit in with that scenario – it isn’t their place to demand that Scotland fit in with them.

Interestingly enough, the Quebec indyref that failed by a whisker in ’95 had polling companies showing a 6 point Yes lead on the eve of polling day. A 6 point lead and it still fell. Current polling for a hypothetical Scottish indyref #2 shows a No lead of 5 points – and that was conducted after the tory outright win last month. Nicola Sturgeon will want to wait until Yes is decisively ahead in these polls before calling another referendum – perhaps a ten point lead or more (as to lose twice would leave them in an untenable position). My personal take on this is that the SNP will begin to lose popularity long before they can ratchet up Yes leads of 10% or more in the polls. Education, health, policing, crumbling infrastructure – several chickens are on their way home to roost.

We have a conservative MP, David Mundell, who serves in the government as Scottish sec. We also have a labour MP from Edinburgh who will serve in the main opposition as Mundell’s shadow. These two men are both Scottish – every bit as Scottish as the SNP members of parliament – and they have power and influence by virtue of the fact they belong to national, non-separatist parties who have a great deal of clout. It’s not Scotland that’s powerless – it’s the SNP.

Now just imagine how much more power Scotland would’ve enjoyed had it returned more tory or labour MPs? More tories would’ve meant more Scots in the cabinet. More labour MPs would’ve meant a smaller SNP surge in the run in, which could have changed the dynamic of the election in England and Wales also – delivering a labour government. Just think about that – a labour government, with its heartland in Scotland and the North, packed with ministers and cabinet members from Scotland.

Instead we have the feeble 56 – most of whom don’t understand or particularly care for parliamentary conventions and tradition.

Imagine the power we would have if we had elected more tory or labour MPs. The fact we didnt elect them means we do not like their policies and do not want them imposed on Scotland. Any unionist MP elected in Scotland would just do as instructed from their head office in England whether that be good or bad for Scotland. This has been tha case for many many years and Scotland has declined because of it. Scotland is not powerless. It is slowly building its power and that is thanks mainly to the SNP. Scots now tend to think for themselves and have flushed out these Unionist pocket lining career politicians. Its time you did the same.

Aldero – the fact that 53 SNP mps are powerless amongst 600 English, for the most part, MPs is the best argument for independence there is.

The Tory vote in Scotland went down. The SNP made unprecedented gains. Ignore that at your peril.

The SNP held an independence referendum. They lost.

They ran in the 2015 election and, despite sweeping gains, are still completely useless in the face of a healthy tory / right wing / unionist majority.

I’d say that’s 2-0 to unionism.

Time and events will do the rest.

I wonder if the 49% shown in the poll above were the 49% that voted SNP in the 2015 General Election. The key group is probably those who feel equally British and Scottish. That describes where I was until 1997; then I became more British than Scottish. Now, I am just embarrassed about being Scottish and have moved into the British not Scottish camp. The Nats have crushed out of me all the pride I once had in being Scottish. I suspect that many more will fell like this as time wears on – the only thing that will disillusion those who have been infected by the plague of Nationalism is when the bills come in and living standards fall dramatically. However by then it will be too late

Are you completely blind to the fact that UK nationalism exists and that Britishness was a modern created identity of a brutal empire….originally Britishness meant a Welsh or Cornish speaker……it was a Celtic term used disparagingly by English elites! Grassroots self rule for all humans in a connected world!

“Now, I am just embarrassed about being Scottish and have moved into the British not Scottish camp, I suspect that many more will fell like this as time wears on”

I suspect not everyone is as stupid as you Iain?

Sorry, but I’m basing this entirely on personal experience rather than any proper research. Like the Sun. 😉

I voted for independence. I’ve never been an SNP supporter. The majority of my friends and family didn’t. Mainly through pragmatism rather than ideology. Some believed in the last minute promises of Gordon Brown, for example.

I reckon that one of the main reasons for Labour’s collapse in Scotland is that they had a binary approach to the referendum. If you supported Labour then you were must be against independence. That alienated a lot of people and also meant that the only manifesto for an independent Scotland was the SNP white paper. It probably won the referendum. I would have preferred to have multiple plans had the referendum gone the YES direction. Had it been YES then labour would have condemned Scotland to 4-5 years of SNP rule without opposition.

A lot of the people who voted NO in the referendum voted for the SNP in the GE. This was not ideological. It’s just that it seemed to be quite clear in the immediate aftermath of the referendum that Scotland would be punished (a feeling which has been cemented by the english press). LIke them or not, the SNP are a Scottish party who are never going to be overruled by the Westminster party. Labour and Lib Dem MPs in the last session have shown that they will toe the party line. 56 MPs who will uniformly oppose anything to the country’s detriment makes sense – a single, reliably bloc. Even those opposed to independence know that at most they can call another referendum. It can still be defeated, if that’s the will of the people.

I’m pretty sure if an independence referendum had been called on the 8th of May it would have voted YES though. 😉

i think the article is pretty much right in its conclusions. My impression is that there is a core vote which one might describe as nationalist, in the sense of my country right or wrong. But I think it’s a pretty small core. For everyone else who has voted Yes or for the SNP, it’s a pragmatic decision based on a desire for a fairer and more democratic society; and it’s based, too, on the fact that the SNP has been a reasonably competent party of government. I doubt if identity per se has very much to do with any of this. It’s not as if we lack an identity.or need to confirm it. From bagpipes to deep-fried Mars bars, from Burns to the Proclaimers, we have miore identity than we know what to do with.

Am hearing at the moment, the BBC catching up on this piece. A few days late, as per.

Agree that the SNP vote wasn’t a pure ‘nationalist’ one though it’s fair to say that most, if not nearly all, of those voters are pro-independence.

I don’t agree with the identity part though. The census was very clear – 63% of us see ourselves as Scottish only. Even those of us with grandparents who many have originated elsewhere in the world.

In all honesty, I know very few people who regard themselves at ‘British’ and most of them are over 60.

Much as I would like him to be right, and think some of the conclusions in his final paragraph likely are, I find Jan Eichhorn’s tone and admonitions in this article to be almost jaw droppingly overconfident. He seems to deliver preemptive and general smackdowns to all and sundry who may disagree with the view he puts forward, at the same time as failing to acknowledge the inherent and well known weaknesses in the procedural foundations of his very view. His unequivocal pronouncements are seemingly made on the basis of a single study series, the SSA. Apart from anyhing else, this should ring alarm bells: the data comes from what he promotes as: “… the high-quality, face-to-face Scottish Social Attitudes Survey (SSA)…”. He doesn’t seem to indicate why this study is so paticularly “high quality”, and one thing that certainly rings alarm bells for me is the “face to face” bit. People are notoriously unlikely to render their true views, particularly to strangers, in a “face to face” interview. What on earth makes him think this feature of the survey would make it more rather than less accurate? Even the fact that the survey is, perforce of “respondents” who would agree to be interviewed “face to face” on this (anecdotally a pretty small cohort of the people I personally know) renders the sample considerably biased from the get go, which is one of the many reasons why these kinds of studies are so fraught with error, and why social science struggles to be a “science”. His tone seems to be one of a series of pretty unequivocal rubbishings of every dissenting opnion or perception, based upon only a single series of data (the SSA) and his words in the third to final paragraph are possibly somewhat telling. He completely fails to acknowledge that in fact, despite his striking confidence, the true interpretation may not be that everyone else is wrong, but that the SSA is not actually giving the clarity of data it should. He asserts that everyone else is misinterpreting reality because the SSA survey says so, without noticing that the SSA survey could just as easily be misinterpreting reality, as so many “well designed” or “high quality” such have done before it! Really, Jan, before you lecture us with such extraordinary and unalloyed (dare I say fresh faced?) overconfidence, can we also have figures 2 and 3, at least?

The article neglects to tell us whether the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey data for 2014 was gathered before or after the independence referendum. I suspect before. The debate around the referendum was so polarising that that a post-referendum survey would likely show a rise in nationalism in the last quarter of 2014 and the lead in to this year’s general election.

Without telling us when the 2014 survey was taken, it’s hard to draw any meaningful conclusions from that year’s data.

The SNP voters aren’t nationalists, and Yes voters weren’t nationalist at all – and it’s frustrating for anyone south of the border to think we are proponents of such an ideology. That is clear with most voters here in Scotland.

But the party itself is still fundamentally nationalist – such an ideology is to cause divisions where arguably there aren’t. There is always an enemy with nationalism, and Westminster is that enemy. And any party within the Westminster bubble is an enemy – even Labour as we saw in this election.

I say there’s not much of a chasm between the SNP and Westminster parties because their policies aren’t actually that radical – apart from independence of course, Take a closer look, and the SNP are a hodge pudge of ideologies, with left wing members and centrist ‘Tartan Tory’ members. There’s actually also some policies that seem quite Conservative – advocating lower corporation taxes, supporting Murdoch, and austerity programmes such as slashing education.

As a Scot myself, I don’t see any of the jingoistic intimidating behaviour that Fleet Street seems to think is the norm north of the border. It’s very sane and rational minded. But I do feel the arguments have been distorted by the nationalistic propaganda from the SNP.

Feel free to cite some examples of this “nationalistic propaganda” of which you speak.

And while you’re struggling with that task, learn that nationalism is not an ideology in itself. It is a component of many political ideologies. There is no single thing called “nationalism”. There are as many forms of nationalism as there are different political ideologies and variations thereon.

The notion that nationalism equals bad is simplistic nonsense. Nationalism can be entirely positive, inclusive and out-going.

In the case of Scotland, though, it clearly does equal bad. It is divisive without bringing any tangible advantages.

Perhaps I can help with some examples of nationalist propaganda? How about “team Scotland vs team Westminster”? “Wastemonster”? Also, “a stronger voice for Scotland”, “bairns not bombs”, “it’s Scotland’s oil”, “once in a generation opportunity”, “it’s as much our pound as it is theirs”, any cover story on The National and much of the content, ” the democratic deficit”, “civic nationalism”, “those people have nothing to do with the SNP”, “the GE isn’t about independence”, “MSM” and “we accept the result of the referendum”. I could go on. A facet of effective propaganda is that it is not recognised as such. Certainly it seems to have taken you in.

My personal favourite was “Scotland is only united if WE vote SNP.” Logically true for any of the parties, no? Although I did like “a stronger/louder voice for Scotland in/at Westminster.” (Oh aye because the number of seats increased proportionally for Scotland if it voted SNP. Nope still 59) Love the sublimanal conflict based position inherent in that argument. i.e. Scotland and by extension it’s MP’s don’t actually comprise the object “Westminster.” (we are in it not of it) Qudos too for the NLP technique of interchanging SNP and Scotland so that they seemed to be the same thing. Also worked when establishing “Westminster” to mean house of commons, the establishment, “them” (as opposed to “us”) and most diabolical of all England/English. A very useful abstract identification label of varying and subjective bias expressions. No matter what your grievances are, It’s “Westminster” to blame and we are anti-“Westminster.” Yep, the SNP have finally grown up into a real political party. Congratulations. ps. There are no “types” of Nationalism. It always boils down to “us” and “them.”

During the referendum, the English revealed that they think they own Britishness.

Today’s Scots seem to have learned to stand up for themselves, and feel easy with the idea that both the pound sterling and Britishness belong as much to them as to anyone else, while the English seem to feel increasingly threatened by this new confidence, seeing it as a threat to their monopoly.

Maybe that’s what this article doesn’t quite convey.

If this article is correct (notwithstanding the valid geographical objections above), people who aren’t nationalists would be wise to stop giving the nationalist cause the oxygen of support. While people may vote for the SNP for a variety of reasons, the party exists for only one reason. Giving them your vote can only strengthen their cause.

Anyone who still imagines that the SNP “exists for only one reason” really wasn’t paying attention to the recent election campaign. Or, for that matter, the last decade of Scottish politics.

Anybody who thinks otherwise had been utterly taken in by them.

Now you’re just being argumentative for the sake of it

Or perhaps you’ve been utterly taken in by them. Their every action is taken to further the cause of independence. They have no other purpose.

That’s the second time you’ve come away with that statement Trevor, by that logic [and I use the word loosely] anything whatsoever the SNP suggest, whether a good idea or a bad one, is perceived by you as ‘they’vs all been utterly taken in’,…Do you not see the irony in your statement?…#gullibleBritnats

There is no irony in my statement. Put simply (for it seems to be required) anything the SNP suggests, whether a good idea or a bad one, is designed to further the cause of independence. This regardless of whether or not the people of Scotland would benefit from independence. Thus anybody who thinks they have any other goal and thinks they exist to benefit the public as a whole, as other political parties aim to do, believes their false rhetoric and has been utterly taken in by them (allow me to save you getting the calculator out: that’s a third time). If you are a nationalist and think a country’s status is more important than the wellbeing of the people who live in it, then by all means support them. If not, and you still do, you are gullible in the extreme.

Jan,

This piece is based on data that is poorly placed to tell you if there had been a rise in nationalism in Scotland recently.

A central tenet of the thinking underlying the article is that any observations regarding the rise of nationalism (or not) should be evidence/empirically based rather than predicated, for example, on anecdote, suspicion or the views of political commentators. However the evidence you use to support your view has a massive flaw. It uses data from BEFORE the main referendum campaign period and the important political events that have taken place since, e.g. the rise in SNP membership to 100,000+.

I notice other research from the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey, when outlining its methodology, states “our 2014 data come from 1,339 interviews that were conducted face to face to a probability sample of adults aged 18 plus living in Scotland between 12 May and 17 July”. (http://www.natcen.ac.uk/media/563071/ssa-2014-has-the-referendun-campaign-made-a-difference.pdf)

Whilst I acknowledge that some debate regarding the referendum took place before this period clearly not only the bulk of it didn’t, but the vast majority of media coverage was also heavily weighted towards the end of the campaign in August and September. This means that any “rise in nationalism” over this period would have been missed by fieldwork taking place for the SSA between the 12th of May and the 17th of July. This is notwithstanding is the fact that of course the Yes and No campaigns officially began a full 18 days after the start of the SSA fieldwork.

Put simply, the collection of the SSA’s 2014 wave data and the referendum campaign were misaligned to the extent that any attempt to infer whether the latter should induce a rise in nationalism (as captured by the former) is deeply flawed. You should have waited for the 2015 data. This mistake is made doubly frustrating as you criticise others for making judgments on this topic that are not evidence/data based while yourself using evidence/data that isn’t fit for purpose.

You use this out of date evidence to inform your opinions and go on to state “crucially, commentators need to stop painting a picture in which the majority of Scotland predominantly base their political decision making mostly on their national identity”. I am not saying a “majority” base their decisions on national identity but I would contend that you are downplaying its importance. I find this stance rather bizarre given that the academic institution you work for produced compelling evidence that indicates otherwise. Prof. Ailsa Henderson’s study of March this year found that:

52.7% of people born in Scotland voted Yes while 47.3% voted No.

27.9% of people living in Scotland but from the rest of the UK voted Yes while 72.1% voted No.

42.9% of people living in Scotland originally from outside of the UK voted Yes while 57.1% voted No.

That same study also found that 90% of Scots that say they are “British not Scottish” voted No, 88% of Scots that say they are “more British than Scottish” voted No and 81% of Scots that say they are “equally Scottish and British” voted No. However, for those identifying themselves as either “more Scottish than British” or “Scottish not British” the figures are only 40% and 11% respectively.

If we were to take an evidence based approach, as you recommend, to judging whether the political decision making of Scots is influenced by their national identity the views of Prof. Henderson’s team are clearly at odds with yours. Given that, obviously, her data was collected subsequent to the referendum I know what evidence is more robust. Her sample size also has the considerable advantage of being much larger than that of the SSA: 4,849 and 3,719 for its two waves vs. 1,339 for the SSA.

Whilst I do accept that there is more to SNP support and/or membership than national identity alone I don’t accept that “there was no rise in Scottish nationalism” or that national identity does not influence one’s political decisions. Sorry, but your conclusions are based on data which is outdated and isn’t fit for purpose, and other work, based on data not suffering from the same flaws points to rather different conclusions. All-in-all, this is a poor article.

There are British Nationalists, typified by their interest in a recently formed Glasgow football team and who support the wearing of the bowler hat alongside items of hi-viz clothing, whose language consists of “staunch” and “no surrender”. Oh, they have such colourful songs too…I could go on.

The point is that the hardcore BritNats serve a purpose in that they unquestioningly support the British Establishment and show little interest in the furtherance of fellow humanity. I am scunnered by some comments which are distinctly colonial towards Scotland!

The SNP/Yes Movement is open and international, not harking on about defending the faith / White Cliffs of Dover from Johnny Foreigner etc.

Could we support some exposure of the BritNat, please?

I know it is a bit late to comment on this but I have just had reason to think about the claim that 52.7% of the voters born in Scotland voted ‘Yes’. If I have my sums right (and I am very happy to be corrected if I don’t) then I think this figure must be wrong.

The problem is we know that the final ‘Yes’ vote was 44.7% and I think we can assume that the bulk of the voters were born in Scotland. If 52.7% of the bulk of the voters voted ‘Yes’ then there don’t seem to be enough voters left over to bring the final percentage down to 44.7%

In essence, there are three variables:

1. The percentage of those born [in/outwith] scotland

2. The percentage of those born in Scotland who voted [yes/no]

3. The percentage of those born outwith Scotland who voted [yes/no]

Once you have chosen numbers for any two of these variables the third one has to be calculated to give the actual result of 44.7%. If you decide that variable 2 is going to be fixed at 52.7% and decide that 85% of the voters were born in Scotland then you have to assume that there was a 100% ‘No’ vote from those born outwith Scotland. This seems unlikely. If you want a more reasonable vote of just over 70% ‘No’ votes from those born outwith Scotland then you have to assume that only two thirds of the voters were born in Scotland. This also seems unlikely.

My reasoning, therefore, is that if fixing variable two at 52.7% makes it impossible to have plausible numbers for variables one and two at the same time there must be something wrong with that figure of 52.7%

What do you think?

You don’t address why identifying as “British” is not nationalist, but identifying as Scottish IS nationalist. I defy you to support this. It is simply a different form of nationalism.

Perhaps it was the author’s intention to deal specifically with national identity but really this is irrelevant to Scottish politics and the civic nationalism which is behind the rise in support for independence and the SNP. Scottish nationalism isn’t some kind of narrow-minded exceptionalism or outright racism it’s really just a desire for a real, bottom-up democracy and good government neither of which seem to be available within the UK.

“british identity” was the wrong question. All who live on this island are British. The question should have read “do you feel more Scottish or part of the UK?”.

“british dentity” was the wrong question. All who live on this island are British. The question should have read “do you feel more Scottish or part of the UK?”.

Many SNP voters aren’t nationalists, and many more Yes supporters aren’t nationalist.

But that doesn’t mean nationalism isn’t evident here in Scotland. The divisory rhetoric that the SNP have spouted has its traces in nationalism (remember the intolerant view that only Yes supporters were part of ‘Team Scotland’ according to the SNP…), creating divisions that aren’t there – and this has all been disguised in the name of ‘social justice’. There is always an enemy to fight against in ANY nationalism – and Westminster – and the Tories in particular – bears the brunt of this strategy.

Yet look closer into the SNP policies and there’s much to suggest deceipt in terms of cuts (they slashed education budgets), corporation taxes (they want it LOWER than the Tories), privatising a section of the NHS to Weightwatchers in a hospital in west Glasgow, constantly sucking up to Murdoch and bowing to his pressure, and also destroying an Aberdeenshire community by letting uber-capitalist Donald Trump build a golf course. The term ‘tartan Tories’ couldn’t be more accurate here – yet nationalism has deluded many SNP supporters in believing their party is radically opposed to anything associated with the Conservatives.

The ‘left’ have been deluded into thinking the SNP are the party of social democracy – but it is one big massive lie that the nationalist agenda coming from within the party has propogated, a successful propaganda machine which has created a massive but false division in Scotland thanks to deceit and lie.

These findings aren’t surprising, but I think the conclusion drawn is wrong. There is a rise of Scottish nationalism, but it is a nationalism that has co-opted the progressive language of the left as a tactic to meet its political nationalist strategic aims (but of course it hasn’t actually adopted the policies of the left – high tax and spend – in order to retain the support of the middle classes – brilliant triangulation!). It’s been so successful at this that it has managed to convince many people to support an explicitly nationalist cause while feeling that they are not supporting nationalism at all.

Another way of putting this is that Scottish nationalism is a civic nationalist movement and not an ethnic nationalist one, and only with the latter would you expect the rise in the movement to correlate with a rise in Scottish identity. But civic nationalism is still nationalism, based on the politics of exclusion and exclusivity, and exceptionalism – certainly in the context of an established liberal democracy.

There is another point worth making. Although this survey doesn’t show a rise in Scottish identity, other surveys have demonstrated the particularity of passion the SNP manages to ferment in its members. I can’t find the link but there was a recent survey which asked the question: Do you feel that an attack on your party is an attack on you? or something like that. For all the UK mainstream parties around 15% to 20% respondents said yes; for UKIP it was up around-odd 30%, but for the SNP uniquely it was over 50%. This kind of fervency is classically symptomatic of nationalism.

So it may be a civic nationalism that many who are not identity politics types are backing, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a nationalist cause. It is a nationalist cause, but just one that’s very clever at winning over parts of the mainstream.

What a load of specious drivel! Who are these “many people” supposedly claiming that the election result proves anything at all about people’s sense of identity? If there are so many people committing this error then how come not a single authoritative voice is cited? And if there are no authoritative voices then what the hell is the point of this exercise?

The election result does not and cannot tell us anything about the personal motivations of voters. It can only tell us about their expressed electoral preferences in relation to candidates and/or political parties. In those term – the only terms that are relevant and meaningful – the conclusion to be drawn from the result is perfectly clear. On an exceptionally high turn-out, half the people of Scotland declared their trust in the SNP to represent them at Westminster. That is more than double the next two preferences combined. More people voted for the SNP than have ever voted for any party in Scotland.

Rarely has there been a more emphatic election result than that. Seldom has there been a more pathetically puerile effort to undermine an election result than this.

The most recent SSA survey took place in early summer 2014, before polls tightened on the referendum and long before the SNP’s post-referendum surge. So it is unsurprising to see attitudes to nationalism appearing unchanged at that point.

Surely the test of this hypothesis can only come from the 2015 SSA, which will judge attitudes after the late referendum swing and after the SNP’s surge. Only then can we establish whether attitudes to nationalism have changed in step.

This article seems, on that basis, significantly premature in its conclusion.

Duncan, you’ve got a cheek calling anything premature.

Remember when you tweeted about how great a speech Gordon Brown had just given, before he had even spoken?

It takes a unique form of delusion to produce such a piece

OR

It is unionist spin (I should have said more unionist spin)

I have been working non stop for several years through the various elections and the YES campaign.

Believe me when I tell you that civic nationalism is on the rise. The problem is that those within the London bubble do not understand the drive to build a fairer society.

56 out of 59 seats and you compile drivel such as this – amazing.

“Civic nationalisms”? You’re not still trying to peddle that notion, are you? Given the Labour and Conservative parties are both practitioners of civic nationalism, it has been established for quite some time. What the SNP offer is a far more divisive brand of nationalism than that.

Only more ‘divisive’ in the sense that it’s ‘Scottish’ civic nationalism as opposed to ‘British’ civic Nationalism. Stop trying to kid yourself one is better than the other

More divisive in the sense that it isn’t civic nationalism at all. Civic nationalist’s do not routinely engage in ludicrous flag waving rallies, for a start.

One thing that the SNP has been pushing is that independence is not incompatible with a British identity as well as a Scottish identity.

So it would be incorrect to assume that those who are equally comfortable with a British identity are against more powers for Scotland or independence.

Britishness and the political union of the UK are not the same thing. Britain relates just as much to culture and geography.

Exactly. The recent success of the SNP has been due to them expanding support beyond the narrow(ing) basis of Scottish-exclusive identification. It’s hard to avoid people who say something along the lines of “I’m not a nationalist, but I’m voting SNP because ….”.

This presents opportunity and danger to the other parties. Opportunity, in that a large part of the SNP vote is not on a purely nationalistic (or even ethnic) basis, which means that they may be open to other offers. Danger, in that it means that the remaining “unionist” vote may also be open to persuasion.

How dare you call freedom , nationalism, how dare you equate nationalistic with independence, how dare you suggest that the Scottish people are stupid, the lies, the scare mongering, the fraud, the cheating , the totally bias and controlled media, do you really think the Scottish people missed all that, because apparently you did, you can directly the rise in the SNP vote to the desire for independence and if you believe otherwise you are either a liar, a politically controlled liar, or a complete idiot, you choose

Did you read the article? Your irate criticism of it has almost nothing to do with what the author has actually said.

..in your opinion. I think it does

From a Scottish population approaching 5.5m – only 1.5m voted SNP in a general election! . . . It somehow gave them 56 seats and good luck to them . . . The silent majority won’t stir until they need to.

Dinglebert. The SNP got 49.97% of the Scottish votes in the General Election. The reason they got 95% of the seats is simple – the first-past-the-post system of voting. The total electorate was 4 million or so, and 71% voted – 5% more than in England.

The 2011 census with 62% stating “Scottish only” and 18% “Scottiah and British” is probably a more accurate indication of how Scots feel about their nationality.

Your silent majority is probably a silent minority by now. Only they’re not so silent. To judge by the Scotsman newspaper’s online comments section many of them are vituperative and ill-informed.

I doubt if this LSE blog has much predictive value, but time will tell however.

You know they cant and will never be able to count Dinglebert, just like they cannot and will not accept a democratic result until it is in their favour. But well said anyway.

Freedom? From what?

Not “from what”, but FOR what. Independence is the ability to freely negotiate the terms on which we associate with other nation. It is the ability to implement policies that address the needs and priorities of the people within a particular polity.

There can now be no question that the political culture in Scotland has developed, and continues to develop, in ways which make it quite distinct from the rest of the UK (rUK). Independence is for recognising that distinctiveness and removing undemocratic constraints on its development. It is for allowing two distinct political entities to each follow the path determined by their electorates.

Always nice to see an abusive, incoherent rant about other people’s biases oblivious to its own. Sums up much of the debate.

Yes. Many of my Scottish friends say they are British! 🙂

…many of my Swedish friends are Scandanavian!

It does not mean that they wish to surrender their status as a nation.

This entire article is based upon a very wrong simple fact. I’m as British as Her Majesty, Elizabeth, Queen of Scots and first started supporting Scottish independence around 1946 as a schoolboy. The author, who is not by any means alone in his mistake, confuses, ” British”, with, “The United Kingdom”.

While, “The United Kingdom”, is indeed, “British”, (it belongs to the geographic archipelago of Britain), it is not Britain. Its title is, “The United Kingdom of Great Britain & Northern Ireland”, and that is but a portion of Britain. There are another four non-UK parts of Britain that are every bit as British as the UK. These are the non-UK Republic of Ireland, the non-UK Bailiwick of Jersey, The non-UK Bailiwick of Guernsey and the non-UK Isle of Man.

The United Kingdom Parliament is NOT the Parliament of Britain, (though since devolution it has become the de facto parliament of the country of England), only now nominally, “The Parliament of the United Kingdom”.

Mr Cameron is NOT, as he so often describes himself, The Prime Minister of Britain and in fact his proper title is, “Her Majesty’s Prime Minister of Her Majesty’s Government of Her Majesty’s United Kingdom. (Her United KINGDOM is actually a bipartite union of her two realms of Scotland & England).

Mr Cameron does NOT have control of the British Armed Forces – only those of Her Majesty’s Armed Forces. Finally Mr Cameron is NOT running, “A”, Country he is now running a quadratic form of countries which are in fact the Master Race of the De Facto Parliament of England at Westminster devolving England’s Powers to three subservient devolved country parliaments. (and he wonders why he will go down in history as the PM who destroyed the United Kingdom of Great Britain & Northern Ireland.

One thing we do know for certain is the growth of anti-Scottish sentiment being expressed by English Tories and the London media in response to the SNP over the past few years. There is no ducking that ugly fact.

Yet its Scots who are tarred as Anglophobes.

The reality is that the SNP have supplanted Labour in Scotland by offering the type of social democratic platform that New Labour explicitly abandoned. Blair’s view that they could afford to chase the middle class Tory vote because the left had nowhere else to go was always short sighted. It has had its answer in Scotland with the SNP at this election. Their success has been built on social democracy rather than nationalism which is why they have proved so attractive to so many ex-Labour members. The same outcome in the rest of the UK in the future is entirely possible but, as with the SNP, will probably have to come from an unexpected source.

Personally, I find it completely implausible that merely “the SNP being more left-wing” could result in the kind of massive swings we saw in the general election in such a short period of time (Labour were leading several general election polls in Scotland shortly before the referendum and the two parties were separated by only 3% in the European elections last year). The weakening of Labour’s hold over Scotland under New Labour perhaps created fertile ground for the SNP to move into that territory, but explaining the entire success in left/right terms is wide of the mark in my view (in fact there was barely much distinction between the two parties in policy terms with the SNP actually planning to spend less in the next parliament than Labour were).

The only sensible comment on the page. I agree with you wholeheartedly.

The fact that a NO voter finds the article so balanced and sensible tells you all you need to know.

If one person finds an article balanced, is that evidence that it is biased in their favour?

How can we tell that an article is truly balanced?

Is it only balanced if “Yes” supporters think it is balanced?

Yep, means we were right all along. We voted NO. !

Whilst I’m surprised at the findings (and note they were undertaken last year when the No campaign was at its most vitriolic) I agree with Peter that the rise in the SNP is not about ‘nationalism’ as understood by the metropolitan chattering classes but about self-determination and a generally left-leaning politics not achievable otherwise in the UK.

So why does the Census – pretty comphrehensive, you’d have to admit – put ‘Scottish only’ at 63%?

I have to agree here: In the 2011 census, 62% of Scots stated they were “Scottish only,” only 18% said “Scottish and British,” while 8% said “British only.”

http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/news/census-2011-detailed-characteristics-ethnicity-identity-language-and-religion-scotland-%E2%80%93

Different questions/categories to choose from and the census is filled in an sort of anonymous whilst the SAS is face to face in your home and people might be less forthright/more socially conformist in that situation.

So the two measures are not directly comparable.

That’s broadly the same figure as shown in the charts – around two thirds of people say they’re “Scottish only”, and a similar portion say “Scottish only” or “More Scottish than British”.

Anyway, the question on national identity was only added in 2011, so a single question from a cross-sectional survey wouldn’t really have any bearing on the argument that there’s no rise in Scottish nationalism.

Interesting evidence of what we have known intuitively for along time: the Scottish independence movement is a social movement not a nationalist one.

I think that’s an over-simplification. Any party that receives 50% of the vote in an election is taking support from a broad range of citizens who all have different reasons for backing it. In the SNP’s case I don’t think there’s any question that at least some of the support comes from a form of nationalism. Part of the SNP’s platform is essentially a kind of nationalist blame politics that seeks to pin every ill in society on to a group of politicians in London who don’t belong to “our group”, who are stealing all of our resources, who marginalise Scottish interests (and so on). Those are all the key elements of nationalist politics, whether it’s defined as civic or ethnic nationalism.

However what’s true to say is that not everyone who votes for the SNP buys into that narrative. The party has managed to broaden its appeal through a mix of anti-establishment politics (positing that independence is the solution to the fallout of the economic crisis) and anti-austerity rhetoric (even though the party’s policies aren’t any more to the left of Labour in many cases and certainly to the right of the Greens). It’s that combination that’s made them so successful, so while nationalism is part of their appeal they’ve managed to attract people who aren’t nationalists to support them.

“Part of the SNP’s platform is essentially a kind of nationalist blame politics that seeks to pin every ill in society on to a group of politicians in London who don’t belong to “our group”, who are stealing all of our resources, who marginalise Scottish interests (and so on).”

It is hardly “blame politics” to note that the politicians in London who have control over Scotland’s foreign policy, budget, trade, defense, immigration and so on enact policy that is not in line with the wishes of the people of Scotland. Westminster is in charge of all those things; the governing party of Westminster was rejected by almost 85% of all Scottish voters, and the largest opposing party in Westminster rejected by 75%.

“The party has managed to broaden its appeal through a mix of anti-establishment politics (positing that independence is the solution to the fallout of the economic crisis)”

No, they posit that independence would allow the people of Scotland to decide how to deal with the fallout of the economic crisis as opposed to politicians who have doubled the national debt in 5 years and presided over some of the most shocking inequality in decades. Nobody is calling independence a magical panacea to cure all ills – simply that we would have some measure of control over what we do about it.

“anti-austerity rhetoric (even though the party’s policies aren’t any more to the left of Labour in many cases and certainly to the right of the Greens)”

And the BNP are further to left on several issues than the Tories: isolated examples are meaningless compared to the whole. It’s not difficult to be to the right of the Greens, for example.

“However what’s true to say is that not everyone who votes for the SNP buys into that narrative.”

Mostly because it’s a narrative entirely invented by opponents of independence who wish to portray the thing 196 countries already do as some sort of crazy notion – or, alternatively, that the UK is a country, and Scotland a region, rather than a coutnry in itself.

Dave Branyan – by your definition, then all of the parties that participated in the GE2015 displayed key elements of “nationalist politics”. Aside from the overt anti-European policies and the usual (falsely important) immigration issues of Ukip and the main two parties, the LibDems say that Britain needs to be closed to “crooks and cheats”, and the Greens mention the “Westminster Establishment” building an “unfair economy” in their manifesto.

One references the tabloid Other of “overseas criminals and benefit tourists”, while the second references a socio-economic Other that is apparent if you substitute “Green” for “Scottish”.

The introduction / abstract states that “It is a mistake, committed by many, *to equate a substantial SNP vote with an **alleged rise in nationalism or nationalist sentiment** in Scotland*”. There has demonstrably been no increase in nationalism, and yet the SNP have increased their vote share.

The article is on the nose: the over-simplification appears to actually be yours, in your assessment of a) what constitutes “nationalist politics” and b) how that nationalist politics are associated with “nationalism”.

@Greg The phrase I used was “nationalist blame politics”. What you’re describing are different variants of blame politics, but not different types of nationalism. Blame has always been one of the most effective ways of mobilising political support, but what separates the SNP and UKIP from other parties is that their “solution” to society’s problems is to get rid of a group of people who don’t belong to “our group” but who are claimed to have a damaging influence over our lives. In the SNP’s case that harmful influence is London/Westminster; in UKIP’s case it’s Brussels/immigrants.

You’ve claimed I’m using an oversimplified definition of nationalism (which is actually a fairly standard definition from nationalist theory) but you’ve offered no definition of your own. In fact in these discussions what tends to happen is people operate from the standpoint that “nationalism” simply means bashing foreigners – and that the mere fact the SNP aren’t anti-immigration means they aren’t a nationalist party. That’s a definition even the SNP themselves reject as they’ve repeatedly defined themselves as “civic nationalists” in the past. The idea that the SNP aren’t a nationalist party is a relatively recent invention that has far more to do with party PR than it does with a change in their platform.

Assuming that’s true, it would be (equally?) true of voters for Unionist parties, not least because they stand for Trident and a united Britain with ‘a strong voice in the world’. Prior to emergence of the SNP in Scotland at least, there was no need to consciously identify this as a reason to vote Tory, for example. However, as a reaction to a party who would seemingly sell out Britain’s international military power and allow more immigration and weaken the UK’s voice in the EU and elsewhere, this form of nationalism is part of Unionist parties’ appeal too. Certainly the rhetoric of unionist parties would suggest this for a start (and considering how many strategists they have nowadays, why would they bother with the rhetoric if it didn’t have appeal).

Are they going to change their name then to SIP?

How dare you use empirical evidence to disagree with what the entire British media and Political Establishment know to be the case without thinking about it?

cummon, dont talk rot, you surely cant believe anything else? Its all a flash in the pan. SNP never have any plans, had no idea what to do. They lost the indy vote, whereas the unionists just pick up the NO result. Pity cos it was all done by the wrong person for purely selfish and egotistical reasons. ( if had not been it could easy have gone the other way) Indy is not a bad thing, being a lemming is though.