With record numbers of young people not gaining university places, the viability of apprenticeships could make a huge difference in preventing a ‘lost generation’ out of touch with the labour market. Dr Hilary Steedman of the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance compares UK provision to our European neighbours, and finds that not enough employers are offering them, and schools should do far more to promote them.

With record numbers of young people not gaining university places, the viability of apprenticeships could make a huge difference in preventing a ‘lost generation’ out of touch with the labour market. Dr Hilary Steedman of the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance compares UK provision to our European neighbours, and finds that not enough employers are offering them, and schools should do far more to promote them.

At the end of 2009 the then Department for Children, Schools and Families estimated that there were up to 900,000 so-called NEETs (that is, young people Not in Employment, Education or Training) in England. This number is likely to have increased since this summer’s university clearing, which saw as many as 28 per cent of applicants still seeking university places only a few weeks ago. Over 16 per cent of 18 year olds fall in the NEET group, while less than 7 per cent of people this age are engaged in some kind of work-based learning, which includes apprenticeships. So there is clearly room for NEETs to move into work-based training such as apprenticeships.

Apprenticeships have historically been an alternative to university education for those leaving school at 16. Measures aimed at encouraging participation in full-time education saw the number of apprenticeships drop from a high of 240,000 in the 1960s to 50,000 by the early 1990s. Largely through the intervention of the last Labour government, these numbers have risen back to nearly 300,000 in the intervening years, with an ambitious target of 500,000 apprenticeships by 2020.

The coalition government however aims to do better; in June, Business Secretary Vince Cable said that it was ‘shocking’ that there were only 250,000 apprenticeships in place. While support for apprenticeships is a part of the coalition’s agreement, they have not as yet laid out their plans for apprenticeships which would succeed Labour’s pledge.

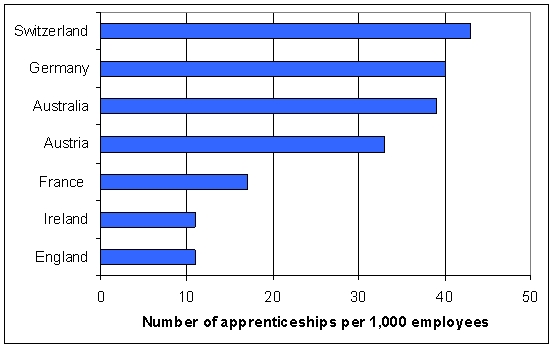

Apprenticeships in England have never been more highly valued by employers and young people, with numbers and completion rates both at an all time high. But many comparable countries are doing as well or better and we need to see what their criteria for success are and what lessons can be learned. My chart below shows key European comparators and shows that despite recent growth, the UK has a significantly lower proportion of apprentices in the labour force than elsewhere.

Apprenticeships in Europe by country

Source: CEP Report: The State of Apprenticeships in 2010

At the same time, fewer than one in ten employers in England offered apprenticeships in 2009, compared with a third of employers in Australia and a quarter in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. And in Germany, almost all the very large firms (those with over 500 employees) took on apprentices in 2005, compared with under a third in England.

Key barriers to the growth of apprenticeships

Schools play an important part in encouraging students to pursue apprenticeships as part of their career path. But in England schools are often hostile to work-based learning and provide little or no assistance. It is often difficult for pupils to access information on apprenticeships. In 2005, two thirds of school students aged 14 to 15 had never heard of apprenticeships. Careers guidance professionals and teachers also often have a relatively low awareness of apprenticeships. More effective careers advice would enable young people to better understand what apprenticeships involve and to fare more successfully in the application process.

Amongst employers in England awareness of apprenticeship is high (90 per cent or more). But this does not translate into high employer participation in apprenticeship. Out of more than a million firms, only some 130,000 currently offer apprenticeships. Small companies are more likely to offer apprenticeships than larger companies. Of the largest companies (500+ employees), under a third (30 per cent) offer apprenticeships.

While desire amongst young people to enter into apprenticeships is generally low, there is evidence that the supply of young people exceeds demand from firms. In 2007-8 a pilot of the Apprenticeship Vacancy Matching Service in Hampshire resulted in 17,000 registered applications for 6,000 apprenticeship places offered. The Apprenticeship, Skills, Children and Learning Act (2009) provides an undertaking that an offer of apprenticeship should be made to all those who want one and who achieve the prior qualification requirement. A National Apprenticeship Service has now been established with responsibility for ensuring that the offer of a place is met.

How apprenticeships work

To gain a full apprenticeship qualification a young person must complete all elements of the appropriate Apprenticeship Framework to the standard specified. These elements must include an occupational qualification, related technical knowledge, and components on functional skills, employee rights and responsibilities, and personal learning and thinking skills.

Apprenticeship Frameworks are available at Level 2 (equivalent to five good GCSE passes) in all sectors and at Levels 3 (equivalent to two A-level passes), and 4 in most sectors. There is no minimum time for the completion of an apprenticeship, but most Level 2 apprenticeships take between 9 months and a year to complete and the longer Level 3 takes between 18 months and two years to complete. Some apprenticeships in engineering and other technically complex occupations will take longer. Apprentices must receive a minimum of 280 Guided Learning Hours per year, of which a minimum of 100 hours (approximately one day a month) must be off-the-job.

In the other countries, longer periods of training (3 to 4 years) help to offset the costs of such training for employers. Other countries also have a higher proportion of apprentices training to the longer level three. Australia, England and France all offer apprenticeships at more than one level of skill: most frequently Certificate 2 and Certificate 3 in Australia, Levels 2 and 3 in England and a range of qualifications in France which start at Level 2 and continue to degree level. Of these, England is the only country where shorter apprenticeships at Level 2 far outnumber those offered at Level 3. In Australia most apprenticeships are at the longer Certificate 3 level and in France just under half are at Level 2. In the dual system (which involves work-based apprenticeships and vocational schooling) countries and in Ireland almost all apprenticeships are at Level 3.

England currently has the highest average apprenticeship wages and shortest duration of training. The minimum wage for apprentices is currently £23.50 an hour for those aged 16-18, and for 19+ apprentices in their first year. As my table below shows, the pay for apprentices generally remains significantly below the level of skilled adult pay:

How much apprentices are paid as a percentage of skilled adult pay, by sector, 2005

| Sector | Per cent |

|---|---|

| Customer Service | 70 |

| Hospitality | 66 |

| Retail | 60 |

| Health | 57 |

| Engineering | 57 |

| Electro-technical | 55 |

| Business Admin | 50 |

| Construction | 48 |

| Motor Industry | 46 |

| Early Years | 44 |

| Hairdressing | 45 |

Source: SSDA Catalyst No. 5 (2008) ‘Time to Look Again at Apprentice Pay?’ Table 4

Funding

For apprenticeships to flourish, paperwork and bureaucracy must be kept to a minimum, which is easier to achieve with simplified funding arrangements – but these are currently rare in England. At present employers pay wages to an apprentice, but the actual training is done by a government-funded training provider (in England, funded by the Learning and Skills Council). Only in large firms with more than 5,000 or more employees, does the government pay apprentice costs directly. Apprentice funding is also stepped – those aged 16 to 18 are fully funded, but for young people aged 19 or more the government only meets half the training cost, which may well act as a disincentive to firms to offer apprenticeships at these later ages. Increasing funding for apprenticeships at these ages might see more 19 year olds and older studying at Level 3, and could raise the total number of apprentices at this level to match more closely with Europe.

In 2009 the Labour government announced that businesses with a proven track record in offering high-quality apprenticeships would be able to access additional funds to train extra apprentices – over and above those they already employ. There are also additional financial incentives (wage subsidies) available to small businesses which employ 16 to18 year old apprentices through one of the newly-established Apprentice Training Agencies. These are positive steps, and it would be good to see these incentives extended to smaller businesses, which now comprise the vast majority of firms in England.

Click here to read the full report “The State of Apprenticeships in 2010”.

Click here to comment on this article.

2 Comments