Looking at how they came to power, their subsequent electoral fortunes, their Cabinet divisions, and their attitudes towards the EU, Ben Williams identifies key similarities between the Major and May governments.

Looking at how they came to power, their subsequent electoral fortunes, their Cabinet divisions, and their attitudes towards the EU, Ben Williams identifies key similarities between the Major and May governments.

The Conservative administrations of John Major (1990-97) and Theresa May (2016-19) are two decades apart, yet incorporate similar overlapping themes and issues which interlink them. Indeed, it can be argued that the high-profile Brexit policy administered by May’s government primarily evolved during the Major era. Both leaders have subsequently become associated with the image of an embattled Prime Minister grappling with high-profile constitutional issues with the potential to damage not only their own party’s fortunes, but also their personal reputations and legacies.

Dramatic rise to power

John Major became Prime Minister in 1990 following Margaret Thatcher’s reluctant departure from Downing Street. Tensions subsequently developed between them, with Thatcher increasingly viewing him as disloyal, and such circumstances undermined Major’s desire to cultivate his own leadership approach. Nevertheless, Major determinedly adopted a more pragmatic and consensual style, while reviving collective Cabinet governance.

In a similarly dramatic scenario, Theresa May succeeded David Cameron in the aftermath of the EU referendum, a gamble that destroyed Cameron’s political capital generated by his 2015 general election victory, when he achieved the first Conservative parliamentary majority since 1992. May was consequently faced with a deeply fragmented party, which evoked parallels to Major’s accession to the premiership over a quarter of a century earlier. In both cases the unexpected departure of a predecessor and EU-infused divisions were certainly in evidence. Yet in contrast to Thatcher’s attitude towards Major (and to May’s relative advantage), Cameron maintained a low profile after leaving Downing Street, acknowledging that he ‘didn’t want to be a distraction for Theresa May’.

Lack of majority

A deep-rooted weakness of both administrations was the fundamental fact that neither enjoyed a significant parliamentary majority. Major’s relatively narrow Commons majority of 21 was gradually eroded by by-election losses, defections, and the suspension of the party whip for several MPs. The ultimate consequence was that by the end of 1996 Major headed a minority government that struggled to get legislation through Parliament.

In also seeking a personal mandate, Theresa May risked the small majority she’d inherited from David Cameron when she called the 2017 general election. She did so in the expectation that she would strengthen her parliamentary position for impending Brexit negotiations, even though in constitutional terms she wasn’t required to for three more years. Yet the volatile result saw her reduced to leading a minority government, and within a considerably quicker timescale than Major did after becoming Prime Minister.

The fact that both Major and May’s administrations existed within the context of small to non-existent parliamentary majorities for the bulk of their premierships has been a principal similarity between them. Consequently, both leaders defeated votes of no confidence in the Commons, and such evident weakness adversely impacted on the capacity of both administrations to control and impose the political narrative of their choosing. This culminated in a precarious situation, whereby each leader became reliant on smaller unionist parties from Northern Ireland to stay in power. Due to such evident fragilities, both Major and May have become associated with a weaker image of leadership compared to more dominant figures like Thatcher and Blair.

Cabinet splits

This sense of ongoing crisis relating to European policymaking not only created parliamentary disunity, but high-profile Cabinet splits also. For John Major, several Thatcherite loyalists remained within Cabinet throughout his premiership, which indicated pragmatic management of senior colleagues on his part. Yet simmering tensions between the old and new regimes spilled into the public domain in mid-1993, when Major (apparently unaware he was being recorded) declared to a journalist of several so-called ‘bastards’ within his Cabinet. The supposed disloyalty of such figures was linked to their relative Euroscepticism and ongoing associations with Thatcher. While there was speculation about who he was referring to, Cabinet divisions peaked in 1995, when Major challenged internal party critics to ‘put up or shut up’, then promptly resigned as party leader, before seeing off the formal challenge from ex-Cabinet member John Redwood. Nevertheless, just over 100 Conservative MPs out of 327 failed to support Major (including abstentions and spoiled ballots), although Major later claimed the process ‘was beneficial in helping to clear the air….. (and) probably decisive in saving my leadership’.

For Theresa May, similar dynamics also prevailed, as she too experienced Cabinet ‘brinkmanship’, with the unprecedented Brexit situation imposing relentless pressure on the country’s political and bureaucratic institutions. May’s unexpected electoral setback of 2017 was influenced by both internal Conservative differences and wider public disagreement regarding her Brexit strategy. Yet the election outcome significantly undermined her previously high degree of authority and legitimacy over her MPs and Cabinet.

By mid-2018, and in a similarly divisive situation faced by Major in the mid-1990s, May’s painstaking efforts to hold her finely balanced Cabinet of ‘Brexiteers’ and ‘Remainers’ together threatened to disintegrate at the height of prolonged Brexit diplomacy. The high-profile sequential resignations of David Davis and Boris Johnson in July 2018 publicly exposed Cabinet unrest, clearly illustrating her declining control over such so-called ‘big beasts’ of government. This highlighted the ever-present danger to her position from potential alternative party leaders. However, May (like Major) also benefited from divided internal opponents, and while the Eurosceptic European Reform Group eventually instigated a leadership contest in late 2018, it failed to oust her at this point. Yet over 100 of 317 Conservative MPs voted against her continued leadership (a similar figure to Major in 1995). Both Major and May were therefore evidently hampered by a divided party and persistent Cabinet splits, largely stemming from the polarising European policy issue.

Electoral fortunes

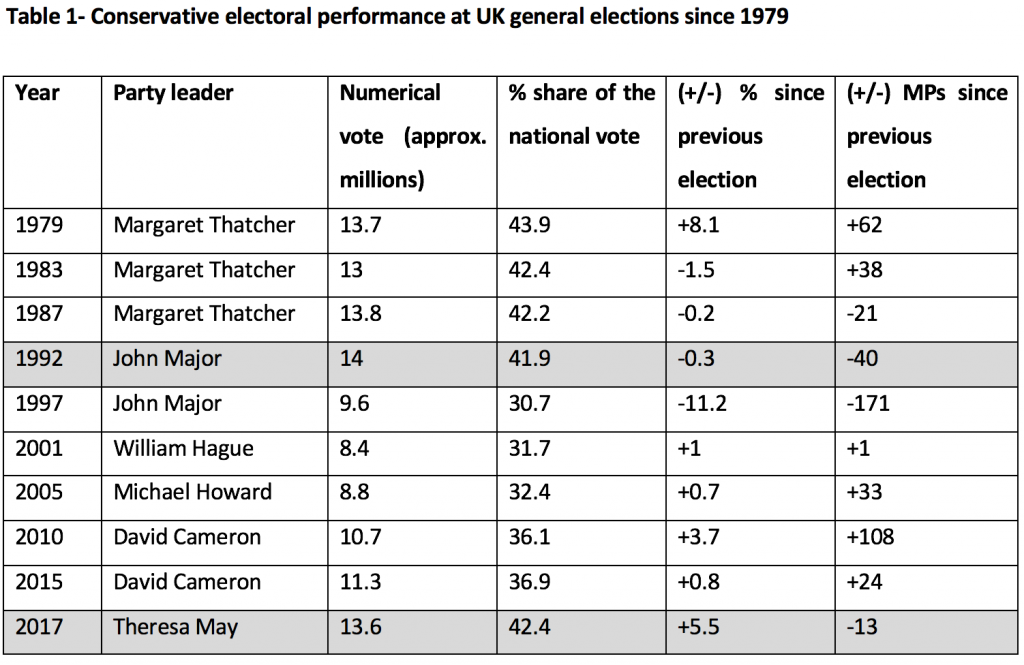

A further feature linking the Major and May administrations is that both leaders secured a similar general election vote while pursuing their own mandate after taking office in the middle of a parliamentary term. In a result which defied opinion polls, Major achieved the highest ever popular vote in British electoral history of just over 14 million (41.9%) in 1992, although this equated to a net loss of 40 MPs. In comparison, May achieved a slightly higher national percentage in 2017 (42.4%) although fewer votes numerically (13.6 million) due to a lower turnout, while also suffering a net loss of 13 MPs.

Unlike Major who waited until the last moment in constitutional terms before calling an election, May operated from a position of relative strength when she chose to prematurely ‘go to the country’ in 2017. Opinion polls had consistently predicted a comfortable electoral victory for the Conservatives, and the election result did constitute an impressive 5.5% increase in the national vote from Cameron’s victorious 2015 performance, reflecting the largest increase in support enjoyed by an incumbent government since 1832. May’s 2017 result was also notable in representing the highest percentage vote for her party in a general election since 1983; and on most comparable occasions it would have equated to an improved parliamentary position.

It can therefore be observed that both Major and May generated a share of the popular vote that no other Conservative leader since the Thatcher era had achieved, yet the often unpredictable quirks of the first-past-the-post electoral system failed to translate into a significant margin of victory for either.

EU policy

The Major and May administrations represent troubled periods of Conservative governance that inter-connect political events across a quarter of a century. Britain’s often tortuous relationship with the EU is pivotal to this comparative analysis, with Europe being the defining political issue of the day under both governments. Both regimes struggled to achieve governing competence while seeking to manage such a contentious political matter with wide-ranging constitutional implications. On this premise, May’s administration appears to have parallels with Major’s in various ways; specifically due to the turbulence of taking office mid-term, the frustrated pursuit of party unity amidst severe political conditions, difficulties formulating a distinctive identity and coherent policy agenda, and an evident parliamentary fragility. All these factors seriously impeded both administrations’ capacity to provide consistent levels of party management and governing competence.

Theresa May’s precarious political position since her election setback of mid-2017 ultimately curtailed any chance of emulating John Major’s six and a half years in Downing Street. This electoral shock hastened her departure, yet she prioritised Conservative Party unity over Europe as much as practically possible, although struggling to achieve this. Her awareness of Major’s political annihilation at the 1997 general election, which heralded an unprecedented 13 years in opposition, would have been a recurring consideration. May therefore sought to protect her party’s longer-term fortunes, arguably at the expense of both her personal reputation and the national interest.

Whether the intensity of the Brexit debate fatally harms Conservative prospects in the longer term remains to be seen, although the party has a fairly durable reputation and has recovered to varying degrees from notable splits in the past. In practical terms, May (like Major) confronted formidable policy challenges, in particular the management of a volatile and high-stakes Brexit process, while also seeking to instil some degree of party unity and governing competence (yet with limited success). This comparative analysis therefore concludes that the inexorable issue of Europe and how to manage it was fundamental to moulding the fortunes of both leaders, and it explicitly destabilised the unerringly similar Conservative premierships of John Major and Theresa May.

_______________

Ben Williams is Tutor in Politics and Political Theory at the University of Salford.

Ben Williams is Tutor in Politics and Political Theory at the University of Salford.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

So the last time the Conservatives had a thumping majority in the House of Commons was 32 years ago?