Citizens’ concerns about data privacy may reduce adoption of COVID-19 contact tracing apps, making them less effective. Based on a choice experiment (conjoint experiment), Laszlo Horvath, Susan Banducci, and Oliver James find that citizens do not always prioritise privacy and prefer a centralised NHS system. They also find support for a mixture of contact tracing done digitally with limited human involvement. On the basis of these findings, they argue that the potential for the adoption of such apps in the UK appears high.

Citizens’ concerns about data privacy may reduce adoption of COVID-19 contact tracing apps, making them less effective. Based on a choice experiment (conjoint experiment), Laszlo Horvath, Susan Banducci, and Oliver James find that citizens do not always prioritise privacy and prefer a centralised NHS system. They also find support for a mixture of contact tracing done digitally with limited human involvement. On the basis of these findings, they argue that the potential for the adoption of such apps in the UK appears high.

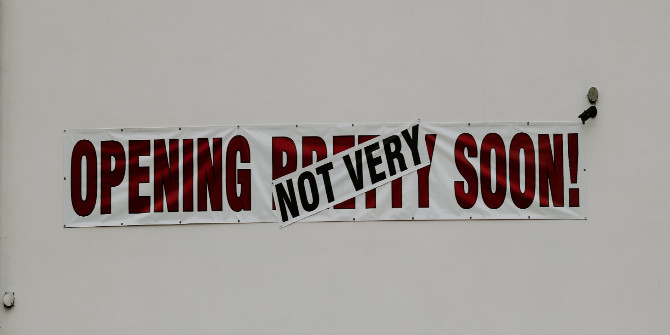

The government recently rolled out its contact tracing app in England and Wales. This launch came about after many stops and starts in developing and trialling an app – six months behind Singapore, the first country to adopt an app, and four months behind the first European apps in Italy and France. An element of a successful test and trace system, digital contact tracing relies on mobile applications and wearable technologies to record when users are in close proximity to one another for an extended period of time, and then notify a user if one of their contacts has tested positive for COVID-19. The app launched in England and Wales, which relies on existing Apple and Google technology to record contacts on the handheld device, also includes features where users can scan a QR code to record their location as well as an isolation counter to keep track of the days spent in isolation if needed.

For effective deployment of the new technology, public trust and confidence is key. Initial interpretations of an Oxford study suggested uptake and use would need to be around 60% for a contact tracing app to be successful, although recent estimates clarify that digital contact tracing is successful at much lower rates as well (at 15%) if combined with other interventions. Yet there is more to confidence-building than those initial adoption rates. In the words of an Isle of Wight GP: “My concern when the public […] will feel ‘what’s in it for me’ and be disincentivised. The truth is very little is in it for them other than the greater good,” the BBC quotes.

Our research was motivated by concerns about privacy as a limit to potential for citizen take-up of apps. In fact, using a conjoint experimental design, we found that citizens do not always prioritise privacy but give high preference to a centralised system led by the NHS over a decentralised system such as the one rolled out. This may be related to the strong support for the NHS during the crisis, one manifestation of this having been the nationwide clap for NHS carers, and the perception that the NHS should be part of the solution for the health crisis. Even when we highlighted a salient threat of unauthorised access or data theft, it did not significantly alter respondents’ preferences. We further find that citizens tend to support a mixture of contact tracing done digitally with limited human involvement. On the basis of these findings, the potential for adoption of apps appears high.

Earlier in the summer, and just weeks after our data collection finished, decisionmakers in the UK abandoned the NHS-led centralised system. According to news reports, this had more to do with technical failure than privacy concerns, though earlier the government insisted that the existence of the centralised NHS server improves the process of contact tracing by making audits and system adaptation possible while also minimising the number of low-risk notifications. While decentralised systems, such as the one being rolled out now, are praised for better overall privacy-preserving features, the lack of central oversight does limit human involvement – in practice, however, this is a legislative feature. After the failure of the first tracking app, it is unclear how meaningfully digital contact tracing will be integrated with the other elements of the test and trace process.

Our findings also highlight additional questions about how citizens’ relationship with their public health authorities affects cooperation with initiatives like digital contact tracing. In the UK, a long history of publicly funded, largely free at point of delivery, high-profile healthcare appears to have created the pre-conditions supportive to cooperate with national public health programmes. This opportunity has not so far been sufficiently exploited but could bode well for adoption of the new app system now that it is finally being rolled out for England and Wales.

The initial uptake of the ‘Protect Scotland’ mobile app launched by NHS Scotland earlier in September is consistent with this view, with over one million downloads within the first week. The challenge will be making sure the government keeps its side of the bargain in rapidly testing, quickly turning around results and then, for those who test positive, tracing contact – providing information quickly enough to those who were potentially exposed to the virus to isolate themselves before individuals transmit the infection to others. The app is only intended to improve the efficiency of the latter stage of an effective test and trace system. As the recent estimates indicate, there are significant issues with the first stages.

It is accepted even among those who are developing and promoting a contact tracing app that it is one tool in a comprehensive test and trace programme. Even if the app is enthusiastically downloaded and used by individual if the rest of the test and trace system, including effective and speedy testing and human contact tracing, is not delivering, the initial enthusiasm on the part of citizens to cooperate may wane.

________________________

Note: the above draws on the authors’ published work in the Journal of Experimental Political Science.

Laszlo Horvath is Research Fellow in the Department of Politics at the University of Exeter.

Laszlo Horvath is Research Fellow in the Department of Politics at the University of Exeter.

Susan Banducci is Professor and Director of the Exeter Q-Step Centre at the University of Exeter.

Susan Banducci is Professor and Director of the Exeter Q-Step Centre at the University of Exeter.

Oliver James is Professor of Political Science in the Department of Politics at the University of Exeter.

Oliver James is Professor of Political Science in the Department of Politics at the University of Exeter.

Photo by Sara Kurfeß on Unsplash.