The number of UK firms at risk of bankruptcy has more than halved in the last six months, while only 6% of all registered businesses say they are at risk – the lowest since September 2020. However, Peter Lambert, Apolline Marion, and John Van Reenen write that the removal of government support, possible new variants, and the ever-present risk of localised spikes in infections could make the rest of 2021 a quite volatile period.

In the six months to July 2021, we have seen a significant improvement in business confidence across the UK in the Business Impact of COVID-19 Survey (BICS) run by the Office of National Statistics (ONS). The number of businesses that reported being at risk of failure in July was fewer than half of those in January 2021. The drop was primarily due to improvements in the outlook of smaller enterprises (those with fewer than 50 employees). The improvement is a cause for cautious optimism, although we also see that businesses are still susceptible to possible disruptions due to new variants or snap policy changes.

To study business confidence, we focus on the question in the BICS that is collected roughly every two weeks. It asks: ‘How much confidence does your business have that it will survive the next three months?’ We classify the proportion of businesses who respond with ‘low’ or ‘no’ chance of survival as being at risk of closing permanently.

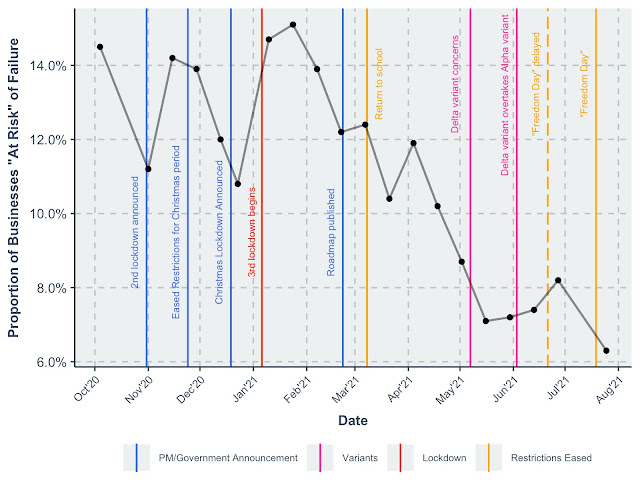

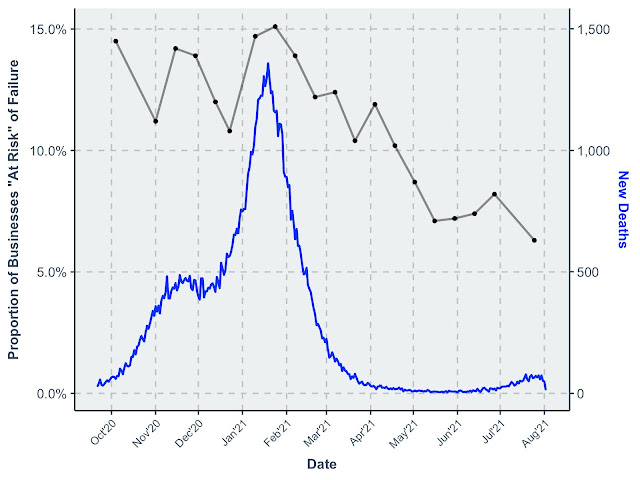

Figure 1 shows how the proportion of at-risk businesses has evolved since the beginning of the BICS survey. The peak in the proportion of firms at risk came from data collected from late December 2020 to early January 2021. This peak coincided with a largely unanticipated lockdown imposed weeks before Christmas. Since this peak, there has been a steady decline in the expected exit rate.

Figure 1. Percentage of businesses at risk of exit over next three months

Note: Data comes from BICS. Our measure of ‘at-risk’ firms is defined as those businesses answering that they had ‘low’ or ‘no confidence’ to the question ‘How much confidence does your business have that it will survive the next three months?’. The BICS survey samples roughly 10,000 businesses every two weeks. We take the closing date of the survey sample window as the date. This question was included in the survey from wave 14 (21 September 2020 – 4 October 2020) to the most recent wave 35 (22 March 2021 – 29 July 2021), excluding wave 15, 34 and 35, where this question was not asked. The responses are weighted by firm size to make them representative. This weighting is done based on the firm employment size distribution from the Inter-Departmental Business Register – which is also the sampling frame for the BICS. Key dates come from a variety of sources, listed at the end of this piece.

The survey question we study has been asked since mid-October 2020, with the first results published in September 2020. We began reporting on these data in January 2021. At that time, things looked very bleak: more than 15% of businesses (one in seven) were on the brink of exit, covering more than 2.5 million jobs. Our follow-up piece in April 2021 showed a mild improvement when nearly 12% firms (one in eight), or 1.9 million jobs, were at risk of being destroyed due to COVID-19.

Cause for optimism

The latest findings show that 6.3% of firms (one in 16) are at risk of failure, covering just over 1 million jobs. This is the lowest level since the beginning of the BICS survey, which began collecting data in September 2020. (The number of jobs covered by this fraction of firms is based on the latest Business Population Estimates, from January 2020. For an outline of the methodology applied, see Appendix A in our earlier report.)

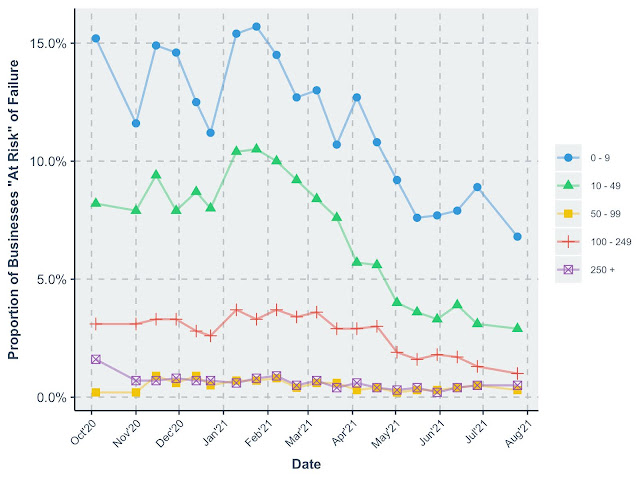

Figure 2 below shows that the most significant improvement in confidence came from micro-enterprises (0-9 employees) and small enterprises (10-49 employees). These were also the most severely hit groups earlier in the pandemic, so it is encouraging that they have responded strongest to the improved business landscape.

Figure 2. Proportion of business at risk of exit by firm size group

Note: See Figure 1 note. The responses within each size band are weighted to make the responses representative, based on the Inter-Departmental Business Register.

What led to the improvement in expected survival? We cannot know for sure what caused the improvement in confidence. Still, we focus on three possible causes: the easing of lockdown restrictions, the significant uptake of vaccinations, and the (related) reduction in deaths from COVID-19.

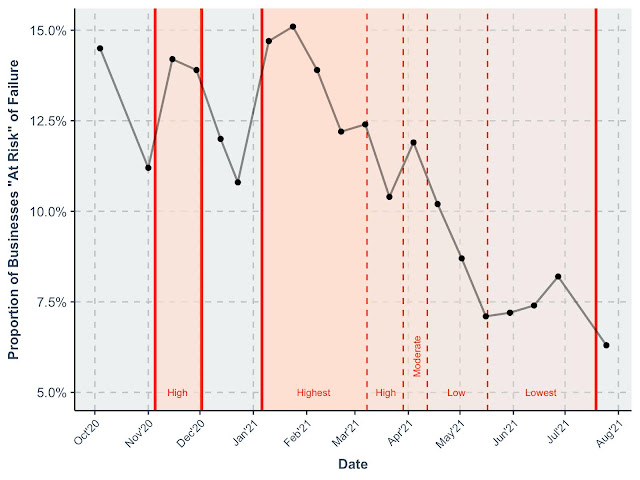

Unlike the many snap changes to policy in 2020 (most notably the strict and sudden imposing of local lockdowns just before Christmas), 2021 has been more stable with a gradual easing of restrictions implemented. The government’s ‘roadmap’, released in late February 2021, planned for a stepped decline in the stringency of measures imposed on businesses and households. Moreover, this forward guidance of the easing of restrictions was mostly rolled out as planned.

Figure 3 below shows how the subsequent transitions from the beginning of a third national lockdown on 6 January through to so-called ‘Freedom Day’ on 19 July, parallel the decline in the number of ‘at-risk’ businesses.

Figure 3. Easing of restrictions

Note: The timing of restrictions data was sourced from various online sources.

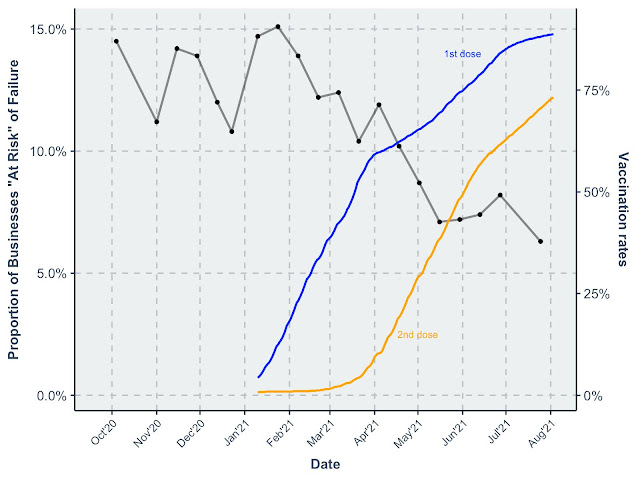

The second notable trend that coincides with the decline in business’ self-reported risk of failure is the uptake of COVID vaccines in the UK. Figure 4 below shows how the proportion of vaccinated people grew strongly (first and second doses) during the period when businesses at risk of exit fell steadily.

Figure 4. Vaccine rollout

Note: See Figure 1 note for discussion of the number of ‘at-risk’ businesses. The vaccination rate refers to the proportion of vaccinated UK citizens aged 18 or above. Single-dose vaccines were counted as both first and second dose for consistency. Data sourced from gov.uk.

Finally, we show how the reduced number of COVID-related deaths tracks the improvement in business confidence. Thus, the reduction in fatalities was both a consequence and a cause of reduced policy stringency and correlated with vaccine uptake.

Figure 5. Declining COVID deaths

Note: See Figure 1 note for discussion of the number of “at-risk” businesses. The number of new deaths was compiled on 04/08/2021, sourced from here. This includes deaths up to 28 days after a new infection is recorded.

Are we out of the woods? The significant decline in business vulnerability is very welcome news. But these data also show that when changes to COVID policies are made abruptly, or threats arise such as new variants, things can quickly reverse. For example, Figure 1 shows an uptick in self-reported risk of failure during May and June. This coincided with the increasing concerns about the Delta variant as well as the announced delays in so-called ‘Freedom Day’.

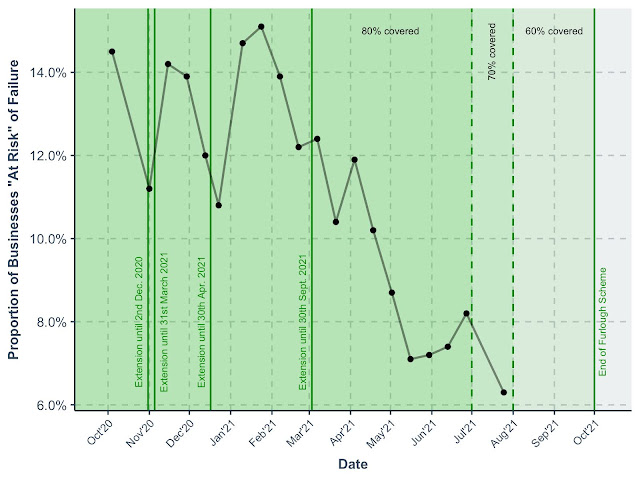

Looking forward, the tapering down of government support for furloughed workers and subsidised loan schemes may give rise to additional volatility in the number of firms at risk of failure. Figure 6 shows the recent history of policy changes, extensions, and current plans to end worker support entirely by 1 October 2021.

Figure 6. Changes to government support for furloughed workers

Note: See Figure 1 note for discussion of the number of ‘at-risk’ businesses. The green lines represent changes (announced or actual) to the Coronavirus Jobs Retention Scheme.

The latest official numbers from HMRC showed that 1.9 million jobs remained on full or partial furlough at the end of June 2021. Even more recent survey data suggests a 31% decline in the number of furloughed workers since these HMRC numbers were released. The ONS BICS survey data asks businesses ‘In the last two weeks, roughly what proportion of your enterprise’s workforce were partially or fully furloughed?’. Responses collected up to 27 June reported that 5.4% of workers were furloughed. Responses collected 25 July 2021 reported that 3.7% of workers were furloughed. The percentage change in these numbers is how we calculate that the number of furloughed workers has fallen by 31% in July. While the end of the furlough scheme will have an impact on employment and business closures, this is likely to slow rather than reverse the recovery in business confidence.

The removal of government support, possible new variants, and the ever-present risk of localised spikes in infections could make the rest of 2021 a quite volatile period. Nonetheless, the UK is in a much stronger place both economically and epidemiologically today than just six months earlier.

_____________________

Note: the above was first published on the Programme on Innovation and Diffusion blog.

Peter Lambert is completing his PhD in economics at LSE, funded by the 2018 Commonwealth Scholarship Award. He also works in the Centre for Economic Performance – Growth Research Programme – as well as for the Programme on Innovation and Diffusion (POID).

Apolline Marion has completed her MSc in Economics at the LSE, and currently works as a researcher for the Programme on Innovation and Diffusion (POID) and the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP).

John Van Reenen is the Ronald Coase School Professor at LSE and the Gordon Y. Billiard Professor of Management and Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he is jointly appointed in the department of economics and the MIT Sloan School of Management. He is also an associate in the Growth Research Programme at the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) and received the Yrjö Jahnsson Award.

Photo by Kai Gradert on Unsplash.