What do gender gaps in voting behaviour in recent elections look like? Rosie Campbell, Rosalind Shorrocks, Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow and Roosmarijn de Geus find that gender gaps exist in support for both large and small parties, but that they vary over time. The political, institutional, and electoral context shapes gender vote gaps in UK elections.

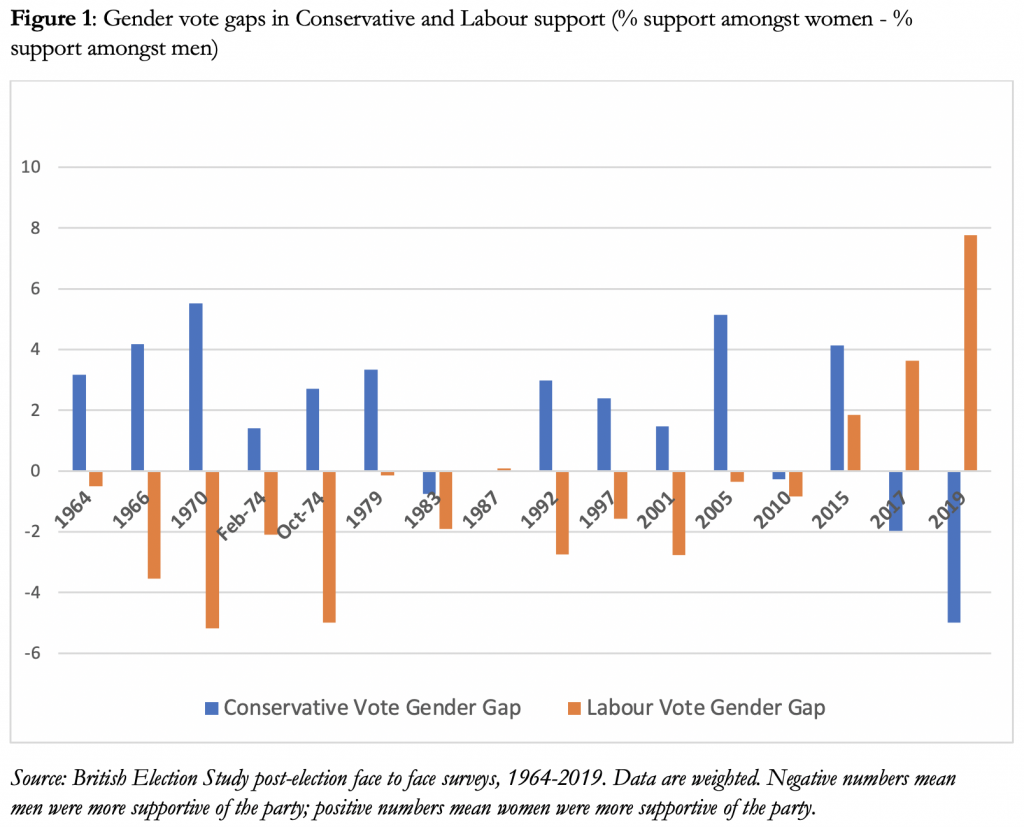

The British election of 2019 saw the largest difference in men’s and women’s average levels of support for Labour and the Conservatives since the early 1970s. The Conservatives had an 18-percentage point lead over Labour amongst men, but this lead was just 5 percentage points amongst women. Even more strikingly, 2019 was only the second election where men were more supportive of the Conservatives than women. Prior to 2017, men supported the Conservative Party at lower or equal rates to their female counterparts. Similarly, prior to 2015 women were never more supportive of Labour than men – but in the last three elections the gap between men and women’s Labour support has widened, and women are now around 8 percentage points more supportive of Labour than men are.

These shifts bring Britain, belatedly, into line with other European countries which have seen growing support for left-wing parties amongst women for decades. This transition has been linked to slow-moving sociological trends such as women’s rising labour force participation and education rates.

In a recent special issue of The Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, we focus on the role of gender in British elections, including the emergence of this gender vote gap. Our analysis suggests that the reasons for its emergence is instead rooted in the specifics of British electoral competition in recent years. It is particularly young women who are supportive of the Labour Party, and this was linked in 2015 and 2017 to their concerns over their financial situation and the provision of services such as the NHS.

In 2019, an election fought even more along Brexit divisions, younger women’s greater anxieties about Brexit, opposition to no deal/’hard’ Brexit options, and support for a second referendum drew them to Labour. Older men and women differed much less in their EU opinions, leading to almost no difference in their vote choice in 2019. The emergence of a persistent gender gap in 2017 and 2019 is thus related to electoral competition over economic support from the state and Brexit. We cannot therefore expect this gender vote gap to persist if political debate moves on in a different direction.

A comparison with the European elections in 2019 highlights the conditional nature of gender differences in party support. In that election, neither Labour nor the Conservatives saw substantial gender differences in support. Women under 35 were more likely to support the Greens than any other party, whilst men under 35 were most likely to vote for the Liberal Democrats.

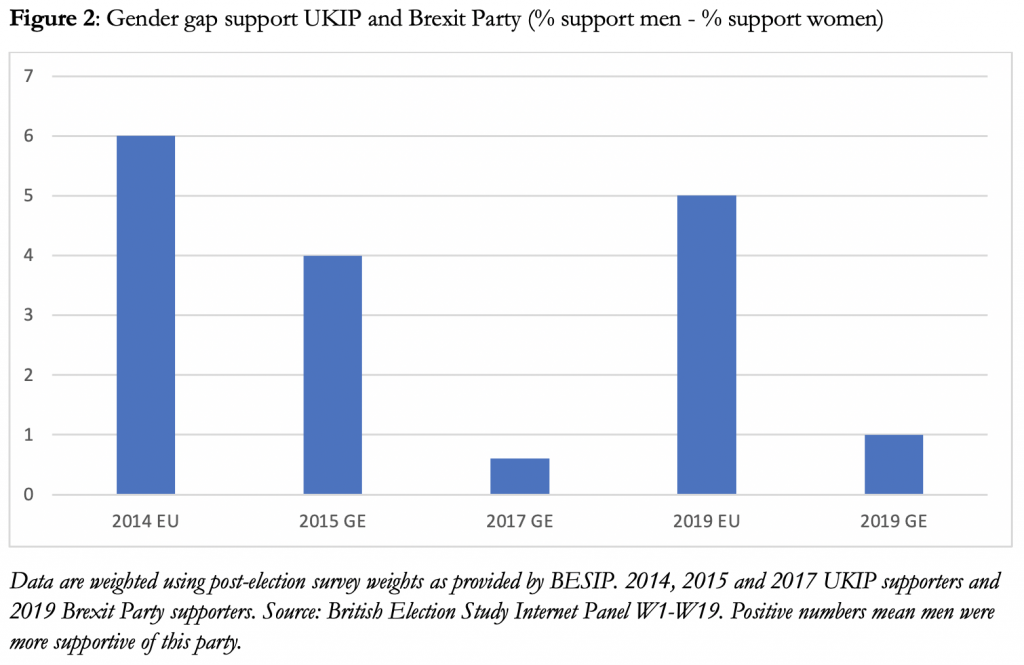

Our analysis of the General and European Elections from 2014-2019 also uncovered gender gaps in the votes for Britain’s most successful populist radical right parties: UKIP and the Brexit Party. Although support for these parties is predominantly male, there is some variation over time; although 6% more men than women voted for UKIP at the 2014 European Election, this number drops to just 0.6% at the 2017 General Election.

Previous scholars have suggested that sociodemographic and attitudinal differences fuel the radical right gender gap. However, our analysis finds that men and women UKIP/Brexit Party supporters have much in common. There are no significant differences in the proportion of men and women supporters with a university degree, and the occupational composition of UKIP/Brexit Party voters generally mirrors that of the population at large. British women are as likely as their male counterparts to endorse authoritarianism, and somewhat more strongly identify as English than men.

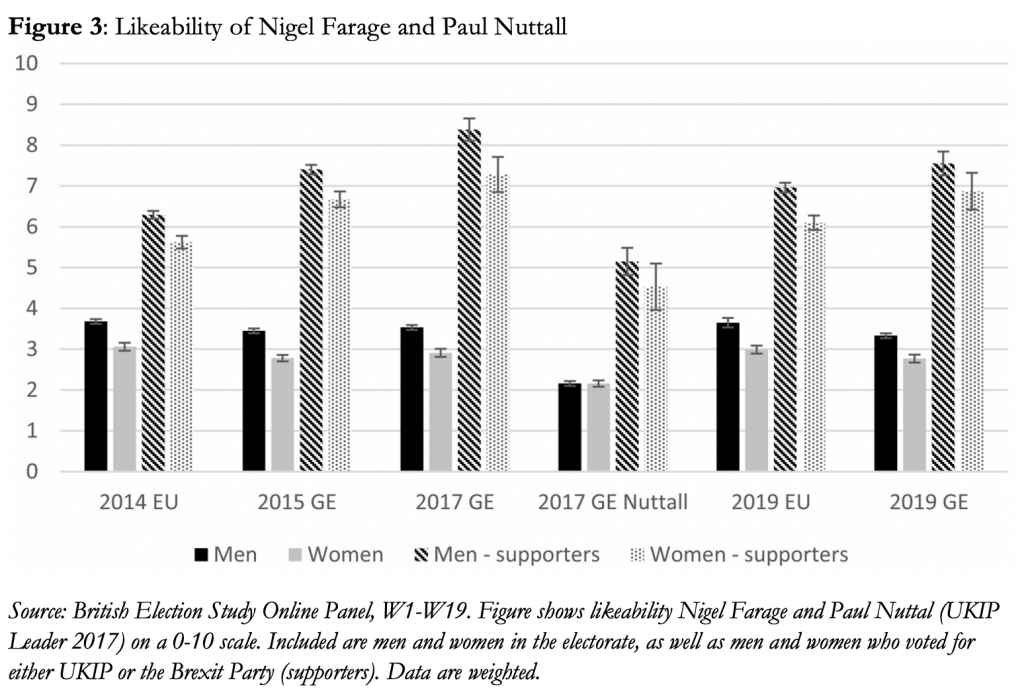

By contrast, men and women hold distinct attitudes about Nigel Farage. Men like Farage at a far greater rate than women; this is the case both amongst the general electorate, and among UKIP and Brexit Party supporters. The differences in Farage’s likeability between men and women are statistically and substantively significant, for instance, just before the general elections in 2019 men gave Farage an average score of 3.3 compared to a 2.8 by women. This difference is similar among those who state they voted for the Brexit Party in 2019, male supporters gave Farage a 7.3, but women supporters gave him only a 6.8 (out of 10). There is reason to think that Farage is a uniquely polarising figure: when we turn to Paul Nuttall, who served as UKIP’s leader during the 2017 General Election, we find that men and women in the general electorate express similar opinions about him.

Attitudes towards Nigel Farage also play a key role in voting for UKIP and the Brexit Party. We find that moving from the lowest to the highest like-score for Farage increased the predicted likelihood of voting for the Brexit Party at the 2019 European Elections by nearly 50 percentage points.

Attitudes towards Nigel Farage also play a key role in voting for UKIP and the Brexit Party. We find that moving from the lowest to the highest like-score for Farage increased the predicted likelihood of voting for the Brexit Party at the 2019 European Elections by nearly 50 percentage points.

It is possible that women may find Farage’s masculine leadership style off-putting, and are then deterred from supporting his parties. Farage is frequently photographed with beer and cigarettes, and commentators have observed that he possesses a ‘man at the pub’ political identity. Additionally, previous research has found that Farage promoted toxically masculine practices during his time as UKIP leader.

That UKIP and the Brexit Party’s success are so connected to Farage raises a potential conflict. Without Farage, his parties may struggle to attract widespread support, but his presence may prevent the party from attracting a greater number of women voters. To further understand this trade-off, future research should consider the extent to which masculine leadership acts as both a draw, and a deterrent, to populist radical right supporters.

Taken together, we suggest that the political, institutional, and electoral context shapes gender vote gaps, even when underlying gender differences in preferences remain similar. Whilst long-term sociological trends create important fundamental conditions for gender vote gaps, political factors have in general been overlooked and need more attention in future research.

_____________________

Rosie Campbell is Professor of Politics and Director of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at King’s College London.

Rosie Campbell is Professor of Politics and Director of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at King’s College London.

Rosalind Shorrocks is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester.

Rosalind Shorrocks is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester.

Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at King’s College London.

Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at King’s College London.

Roosmarijn de Geus isLecturer in Comparative Politics in the Department of Politics & International Relations at the University of Reading.

Roosmarijn de Geus isLecturer in Comparative Politics in the Department of Politics & International Relations at the University of Reading.

Photo by Dainis Graveris on Unsplash.