The announcement of a new visa for young, professional Indians to work in the UK could prove popular – but an eye needs to be kept on how it ends up being used in practice, writes Alan Manning.

The announcement of a new visa for young, professional Indians to work in the UK could prove popular – but an eye needs to be kept on how it ends up being used in practice, writes Alan Manning.

As part of a wider agreement to foster links between their countries, the UK and India have announced a Young Professionals Scheme (YPS). This will be open to a maximum of 3,000 18-30-year-olds from each of India and the UK per year, although the two governments can decide to raise or lower this limit. Those taking part must have graduate-level training relevant to their work and be able to express themselves in the language(s) of the host country. They will not be allowed to bring any dependents.

Youth mobility schemes

The proposed YPS is outwardly quite similar to existing Youth Mobility Schemes that the UK has with Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Japan, Monaco, New Zealand, South Korea and San Marino. Youth Mobility Schemes have traditionally been thought of as part of cultural exchange, giving young people the opportunity to live in another country for two years and to earn enough money to be able to support themselves without restriction on the type of work they do. The traditional image in the UK is of an Aussie wanting to see a bit of Europe or a Brit wanting a bit of Aussie sunshine.

But a Youth Mobility Scheme (YMS) visa can also be attractive to some as a form of work visa. And because these visas are not tied to a particular employer or type of job, those on these schemes end up in all types of work. In the UK, we don’t know what type of work is done on the YMS because it is not a requirement of the visa to keep such records.

The existing YMS are all between high-income countries which have been perceived as low risk (e.g. of participants over-staying). So the agreement with India is an interesting innovation – the country has many very highly skilled workers but still has many very poor people. There are many lower-skilled Indian workers in places like the Gulf who would be interested in spending two years working in the UK where they would earn much more. The provision that the YPS is only open to professionals is to make sure that this route is not open to that group of workers. Nonetheless, I suspect that the route will be heavily over-subscribed. On other YMS schemes, this is handled through a lottery; the Memorandum of Understanding in the case of the YPS is silent on the matter. On the face of it, this new agreement is about people, not businesses. But one thing to keep an eye on is how this works out in practice.

For people or businesses?

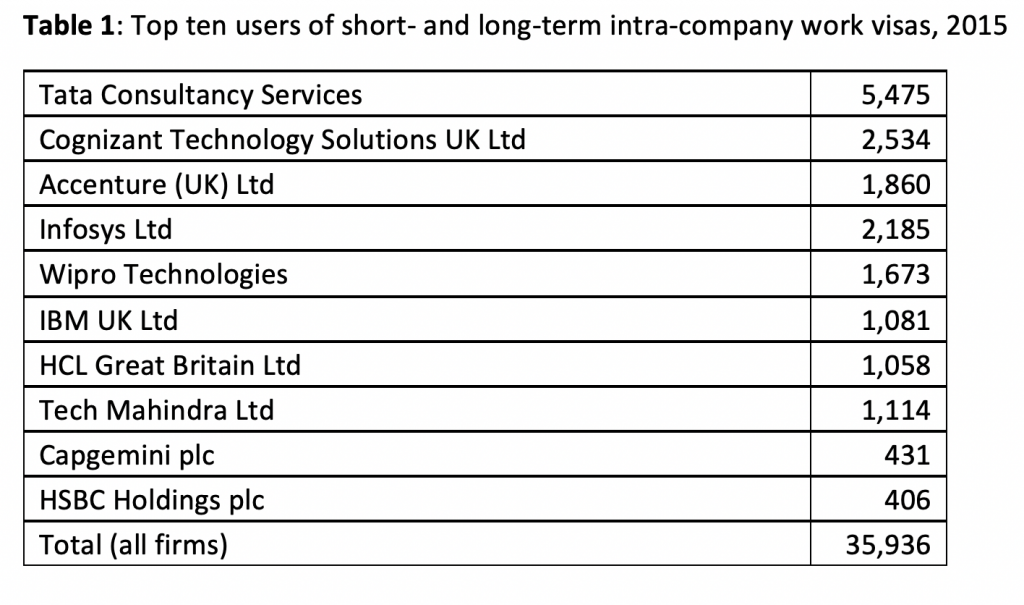

Some of the biggest users of the Intra-Company Work Visas in the UK have been the big Indian IT out-sourcing companies. The latest figures I can find are for 2015:

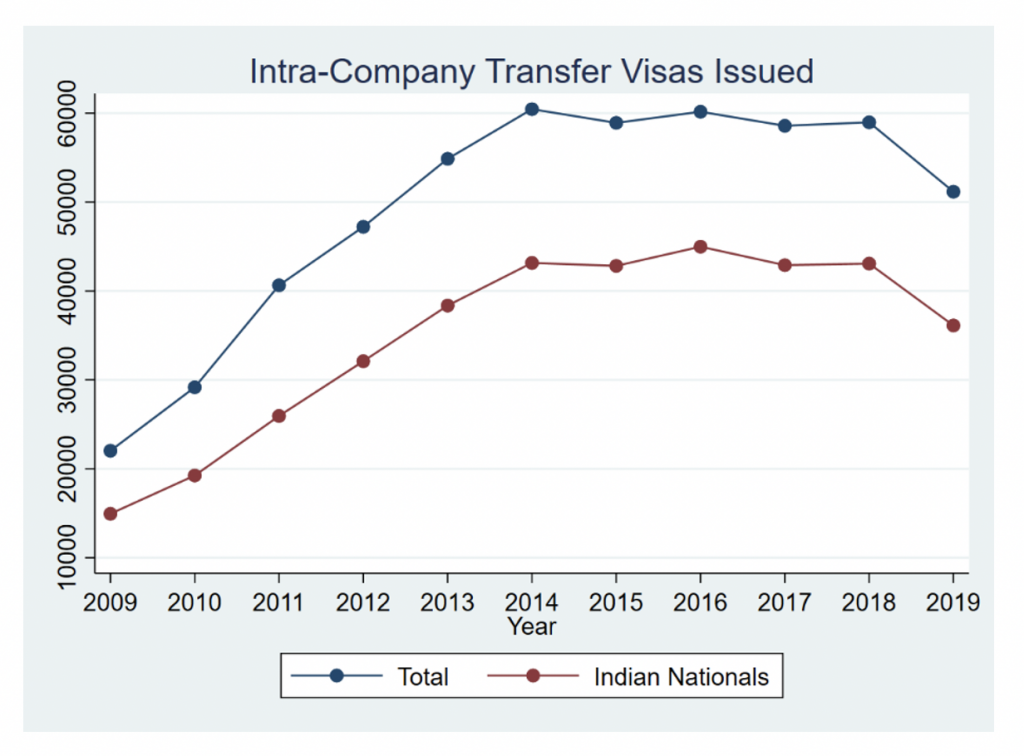

I suspect more recent figures would show something similar. Many of these companies are Indian or have strong links to India. The vast majority of workers on these visas have always been Indian nationals as the figure shows: 70% in 2019.

I suspect more recent figures would show something similar. Many of these companies are Indian or have strong links to India. The vast majority of workers on these visas have always been Indian nationals as the figure shows: 70% in 2019.

Use of the Intra-Company Work visa has been controversial. The visa was designed to be used by multinationals for short-term postings of senior workers for delivery of one-off contracts. But some of the biggest users have been accused in the past of using this route to staff permanent roles with a revolving set of personnel. In other words, they are accused of outsourcing British jobs. According to a 2015 Migration Advisory Committee report into the route: ‘Some partners (usually individuals rather than employers) submitted evidence claiming that undercutting and displacement was taking place. We also received evidence making allegations of abuse of this route specifically in relation to IT occupations.’ Partly as a result of this concern, the minimum salary threshold is currently set at £41,500 (though there is a current Migration Advisory Committee commission looking at it).

Although there are criticisms of the use of the Intra-Company transfer route, there also arguments for the way the current scheme works. A wide range of British companies are able to obtain high-quality IT services at a good price and this helps a wide range of industries in the UK. The Indian IT companies also want to be able to bring workers to the UK under less restrictive conditions. There is an enormous supply of highly-skilled IT workers in India where salaries, though rising, remain below UK levels. These companies have made a lot of money by offering high-quality services at a price that allows them to benefit from the differences in salary levels. These companies would love to be users of the new YPS as, unlike the existing Intra-Company Transfer route, there seems to be no minimum salary thresholds, maybe not even any monitoring of the jobs being done. But how could these firms use the YPS if it is an individual scheme, probably over-subscribed, in which places are allocated by lottery?

The US experience with the H1B Lottery

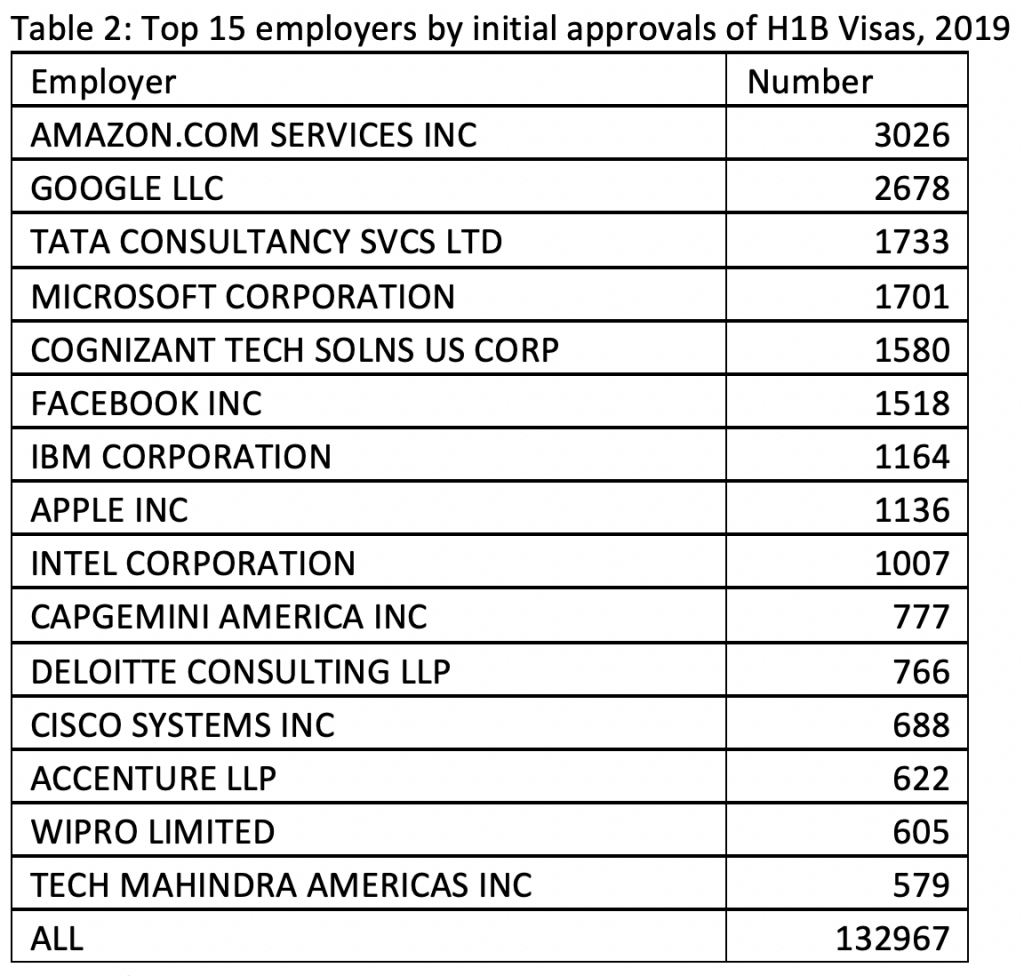

The companies probably have a way of handling the lottery part. The US runs a temporary work visa, the H1B, which has a cap, is heavily over-subscribed, and is allocated by lottery. Nonetheless, a relatively small number of employers come to dominate the approvals – as Table 2 shows.

Source here.

Source here.

There is considerable overlap with the top users of the above and the Intra-Company Transfer route in the UK, while over 50% of the migrants using the H1B visa are from India. The use of this visa has also been controversial in the US for many of the same issues as have arisen in the UK: under-cutting American workers and outsourcing American jobs.

The H1B programme is an employer-led visa where it is hard for workers to change employers. In contrast, the YMS (and probably the YPS) is an individual-led visa where the successful applicants are free to change employers. There is nothing, however, to stop applicants being current employees of companies and working for those companies in the UK. These applicants would be unlikely to change employer once in the UK when they have a permanent job back in India. And the reported eligibility conditions seem designed to suit the employees of the big IT companies. The restriction to Indian nationals will give Indian companies an advantage over other heavy users of the Intra-Company Transfer route. The proposals lack some detail: how are visas to be allocated if they are over-subscribed and what is the exact link to work, which is not in the YMS but seems more prominent in the YPS? As is often the case, the devil will be in the detail.

Conclusion

The bottom line is that an eye needs to be kept on how the new YPS visa is used in practice. If it is used by a wide range of young Indians doing a wide range of jobs to foster greater links between the two countries, that would be a great thing. But there is a risk it ends up primarily benefitting a handful of companies and becomes something more like the Intra-Company transfer route but without the protections against under-cutting and outsourcing that route currently contains. That would be a bad outcome.

___________________

Alan Manning is Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics and co-director of the Community Wellbeing Programme at the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics.

Photo by Onkarphoto on Unsplash.

Dear Alan,

Thank you for your views on this scheme. I recently completed my Master’s from Sheffield University and in my field of interest and working, I can count about 7 companies who are the Sponsor License holder. I was sort of fuming that if I might have joined my Master’s course in 2020 instead of 2019, I might have had got the benefit of 2 year PSW and returning back to India in March 2021 was such a weird and unhappy moment for me because I didn’t get any job opportunity due to the fact that companies weren’t having sponsorship provision or the ones who had (7 of ’em) were either reluctant to offer me the CoS or didn’t reply until yet.

So a guy like me who wish to live in Britain for sometime and work in my own field (a naive for now), this is a fabulous opportunity for someone like me. Hoping the scheme doesn’t gets overtaken by what you have mentioned above. I’d love to also hear your views for such people like me who studied there and had to come back due to unemployment.

Cheers!

Dear Alan,

I fully agree with you on, the devil is in the detail. Many U.K.SME businesses are applying to Tier2 sponsorship and then selling Tier2 jobs to international students.

These students then earn their own salaries by working cash in hand jobs and depositing it to its Tier2 employer.

Young Professional Scheme over subscription will lead to a huge collection of administrative fee of £244 which I guess is non Expression.

I wish YPS is by invitation on basis of an Expression of Interest to chose the best 3000.