Is contact with other ethnic groups itself enough to foster integration? James Laurence explores the attitudes of those who have had such contact in their neighbourhood and workplace. He explains that, although mostly positive, social mixing can also be negative for some, leading to more polarisation. But the negative impact is much weaker in workplaces than in neighbourhoods. He argues that with this knowledge, policies that encourage a diverse workforce could play a vital role in fostering positive relations across society.

Is contact with other ethnic groups itself enough to foster integration? James Laurence explores the attitudes of those who have had such contact in their neighbourhood and workplace. He explains that, although mostly positive, social mixing can also be negative for some, leading to more polarisation. But the negative impact is much weaker in workplaces than in neighbourhoods. He argues that with this knowledge, policies that encourage a diverse workforce could play a vital role in fostering positive relations across society.

As the UK becomes more ethnically diverse, how we build positive relations between ethnic groups is a crucial question for society. More social mixing is held as a key means to this end. The recent governmental Casey Review on integration, for example, stresses how a lack of social mixing acts as a critical barrier to integration.

But, although most people’s contact with other ethnic groups is positive, a small number have negative experiences; and while the former become warmer towards other ethnic groups, the latter become much colder. The result is that as society becomes more diverse, some people become increasingly hostile towards other ethnic groups as a result of, and not due to a lack of, contact.

Mixing between ethnic groups is a key method of reducing prejudice. This puts increasing ethnic diversity in a unique position: while it can foster feelings of threat towards other groups, it also increases opportunities for contact. The same phenomenon potentially driving tensions thus brings its own opportunities to resolve them. A common view therefore is that to cultivate better relations in diverse societies we just need to encourage greater mixing. However, this rests on the assumption that all mixing is positive. What has been overlooked is that contact can also be negative and that the more negative contact one has the worse one’s views of other groups become.

If increasing diversity leads to more mixing but mixing can also harm relations between ethnic groups, what are the implications of this for building integration through social mixing in diverse societies? This is what our study set out to explore.

Neighbourhood ethnic diversity, prejudice and the roles of positive and negative social contact

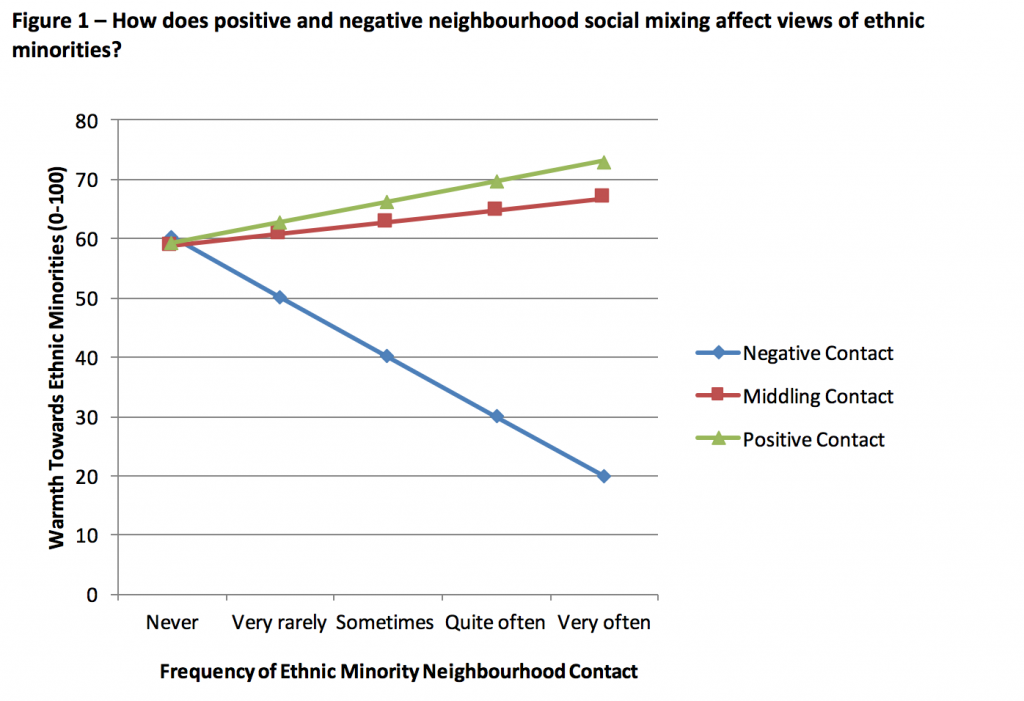

Figure 1 shows the reported warmth towards ‘ethnic minorities’ (on a scale of 0-100) among a nationally representative sample of White British individuals surveyed in England in 2008. Respondents were first asked how much social mixing they had with ethnic minorities in their neighbourhood.

However, in a rare occurrence for such studies, they were then asked how much they enjoyed this contact. Those who said ‘I enjoy it a great deal’ were classed as experiencing positive contact, those saying ‘I enjoy it quite a bit’ and ‘I enjoy it a little’ as experiencing middling contact, and those who said ‘I don’t enjoy it very much’ and ‘I don’t enjoy it at all’ as experiencing negative contact. How these different types of contact affect warmth towards minorities is striking.

More frequent neighbourhood contact does lead to warmer attitudes towards minority groups: both positive and middling contact have positive effects. However, when individuals reported they didn’t enjoy this contact, frequent mixing led to much colder feelings towards minorities. Furthermore, this negative effect is far stronger than the warming effects of positive/middling contact. Negative contact therefore actually leads to worse outcomes than if someone had no contact with ethnic minority groups at all.

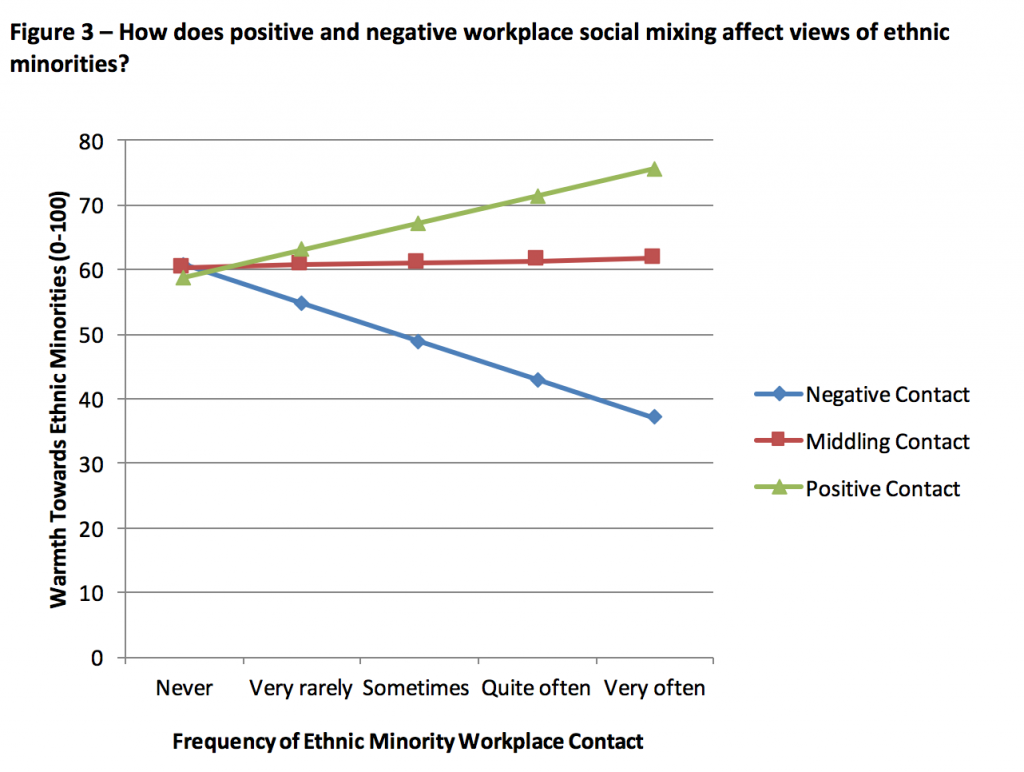

This could lead to a key problem: as diversity increases, it might not only provide more opportunities for positive contact but also opportunities for negative contact. Using the same sample of White British individuals we looked at this. Figure 2 shows how much positive, middling, and negative contact is experienced as neighbourhood diversity increases. On the whole, positive and middling contact is much more common than negative contact at higher diversity. However, all types of contact become more frequent in more diverse neighbourhoods. In other words, diversity leads to both more positive and more negative contact.

Let’s pull these findings together. The good news is that the net-effect of ethnic diversity on people’s views via mixing is positive. In more diverse neighbourhoods, most people experience more frequent positive or middling contact, and those do report more positive attitudes than if they had no contact at all. The bad news is that, as diversity increases, a small number of people experience more negative contact and (although far fewer in number) those who do report much more negative views of ethnic minorities.

Let’s pull these findings together. The good news is that the net-effect of ethnic diversity on people’s views via mixing is positive. In more diverse neighbourhoods, most people experience more frequent positive or middling contact, and those do report more positive attitudes than if they had no contact at all. The bad news is that, as diversity increases, a small number of people experience more negative contact and (although far fewer in number) those who do report much more negative views of ethnic minorities.

As neighbourhood diversity increases a segment of communities therefore become much colder towards ethnic minority groups as a result of contact. In fact, diversity can polarise attitudes towards ethnic minorities via more frequent mixing. This has critical implications for efforts to build positive relations through greater mixing.

Workplaces as Sites of Integration

Policies have largely focused on building integration through residential communities. As we see, this can have negative unintended consequences. Yet, encounters with ethnic difference also occur across our workplaces. In fact, people in England self-report that their workplaces are more diverse than their neighbourhoods – 33% report their workplaces being ‘about half’ or more non-White British while 24% report their neighbourhoods are ‘about half’ or more. Yet there is little focus on how diverse workplaces may foster integration.

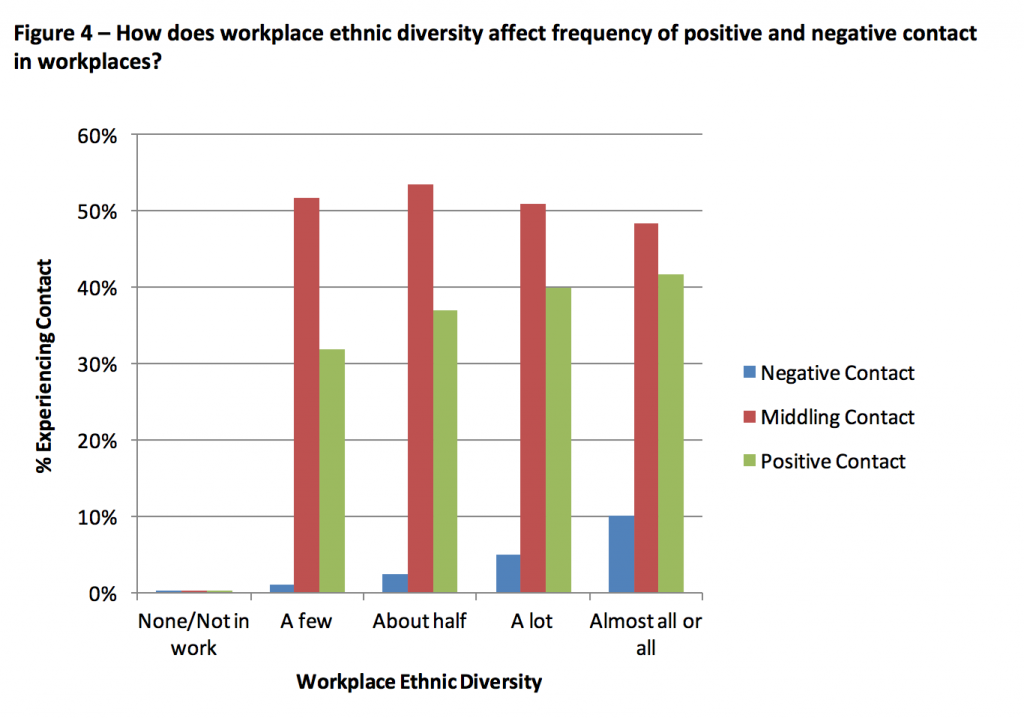

Let’s look again at how different types of contact affect warmth, but this time in workplaces. Using the same sample of White British individuals Figure 3 shows that having more frequent positive workplace contact with ethnic minorities has a similarly warming effect as across neighbourhoods. More middling workplace contact tends to have no effect on attitudes. Yet crucially, negative workplace contact has a much weaker cooling effect than negative contact in neighbourhoods.

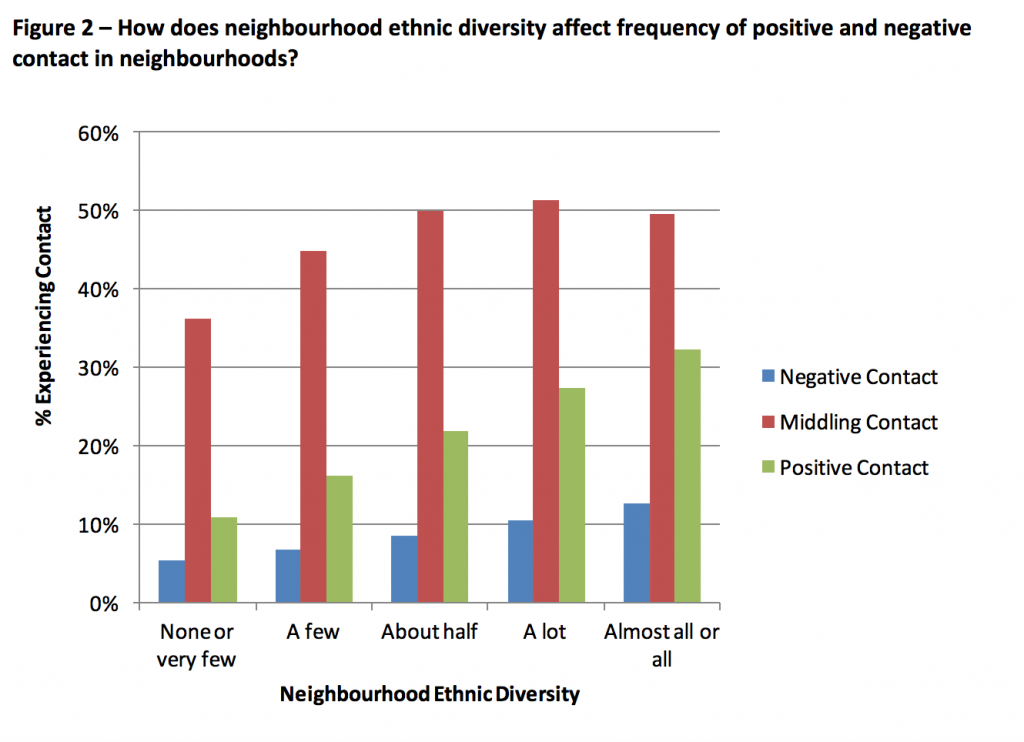

How does workplace diversity affect different types of contact compared to neighbourhoods? Figure 4 shows that being in a more diverse workplace similarly leads to more frequent positive and negative contact. However, compared to neighbourhoods, positive and middling contact experiences are more common and negative contact less so.

Again, let’s draw these findings together. On one hand, diversity in workplaces can also polarise attitudes towards ethnic minorities via more mixing. On the other hand, with more positive and less negative experiences, and negative experiences having a weaker effect, workplace diversity looks better at cultivating positive relations between ethnic groups.

Implications

As diversity in the UK increases, a lack of mixing between ethnic groups is frequently cited as biggest barrier to integration. The good news is that the net-effect of mixing in diverse environments is positive. Encouraging more mixing will, generally speaking, improve relations between groups. However, careful attention has to be paid to maximising positive experiences and minimising negative ones. Without this, not only are the benefits of mixing not realised but, at worst, more mixing may drive a growing polarisation in people’s views towards other ethnic groups, and create an increasingly hostile segment of society.

In lieu of this, workplaces offer a key context, outside of communities alone, for driving integration. Policies should be further encouraged that limit employment discrimination, encourage diverse workforces, as well as eliminate ethnic and socio-economic inequalities in access to, and participation in, all levels of the workforce. As UK diversity increases, workplaces could, more and more, play a vital role in fostering positive relations across society as a whole.

_____

Note: the above article draws on the author’s co-authored work in Social Indicators Research.

James Laurence is an ESRC Future Research Leaders Fellow at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research and Department of Sociology at the University of Manchester. His current project, the ‘Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Ethnic Diversity, Socio-Economic Inequality and Social Cohesion’, explores the role of ethnic diversity, immigration and inequality in the creation and dissolution of social capital, cohesion and inter-group relations. His other research interests include the impact of micro- and macro-scale economic hardships for social, civic and political attitudes and behaviours, and ethnic-inequalities in violent crime.

James Laurence is an ESRC Future Research Leaders Fellow at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research and Department of Sociology at the University of Manchester. His current project, the ‘Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Ethnic Diversity, Socio-Economic Inequality and Social Cohesion’, explores the role of ethnic diversity, immigration and inequality in the creation and dissolution of social capital, cohesion and inter-group relations. His other research interests include the impact of micro- and macro-scale economic hardships for social, civic and political attitudes and behaviours, and ethnic-inequalities in violent crime.