Government plans will leave universities at risk from forced private sector borrowing and even financial takeover. Andrew McGettigan writes that the shift in balance between public and private university finance will spark negative consequences for governance of academic institutions and for public interest.

Government plans will leave universities at risk from forced private sector borrowing and even financial takeover. Andrew McGettigan writes that the shift in balance between public and private university finance will spark negative consequences for governance of academic institutions and for public interest.

The government’s plans for higher education have provoked protest and debate. Criticism have largely focused on the cuts to the grants, higher tuition and increased graduate debt. Party politics is also funnelled through this bottleneck. Labour therefore positions its counter-policy through a lower tuition fee cap of £6,000, while the Liberal Democrats can discuss reversing fee rises or abolishing them altogether, were they somehow to win outright power in a future election.

This aspect of the policy is presented as if reversible, but neglected parts of the white paper and technical consultation, drafted with vague formulations and open-ended questions, intimate more profound, long-term transformations. These clauses relate to privatisation of higher education through new forms of financing, changed legal status and opportunities for investment. From this perspective various think tank reports have been more influential on government policy than the Browne review.

In September, Research Fortnight launched a series, The Third Revolution, to initiate a debate around these potential changes. What are universities, who owns them and how will they differ in future? Beyond higher tuition fees and reduced public funding (revolution 1) and the artificial recruitment mart (revolution 2) something less transparent is in the offing which needs to be extracted and debated if we are not to suffer the erosion of our public higher education system without proper democratic oversight.

Would you welcome legislative change to make the process of changing legal status easier?

That is Question 21 in the BIS Technical Consultation document that was published without fanfare in early August. But why might university management or ‘you’, want to change legal status?

The White Paper had raised the issue but couched it so as to disavow ownership of the idea: “it has been argued that it would be helpful to institutions to ease their ability to convert to a legal status of their choosing”. (§4.35)

But what exactly is at stake here? Universities in England for the most part fall into four general categories:

- Oxbridge and Cambridge, which are civil corporations;

- Pre-1992 universities, numbering around 50, are corporations in receipt of a Royal Charter;

- Companies limited by guarantee, of which there are about 25, mostly the newer, post-2000 universities, but also institutions such as LSE, and the Polytechnics overseen by the Inner London Education Authority;

- Higher education corporations, the other former Polytechnics, formed by the 1988 Education Reform Act, when they were separated from their local education authorities. They still maintain a quasi-public status.

Allowing the established universities to convert to a legal form of their management’s choosing means maximising access to private finance to replace lost public funding. For example, higher education corporations may prefer to convert to companies limited by guarantee, who have the ability to issue bonds and other financial products.

But the government’s consulation indicates a further possibility. We are used to hearing of the creation of a level playing field which will allow alternative education providers to enter the sector. This will create novel conditions of competition between charities, which have certain tax advantages, and potentially profit-making vehicles which have access to equity investment. This competition may not be to the benefit of many established universities and they may prefer to ditch their charitable status and ape the legal form of the new competitors whether a company limited by share or a company floated on the stock exchange.

Glynne Stanfield of Eversheds legal firm argues in a recent report that some universities need new levels of investment simply to remain competitive. Recently we outlined why a university might need to seek such private equity investment. Middlesex University is an example of a corporate plan that has unravelled owing to the collapse of its overseas strategy. The university is now heavily indebted and will have difficulties in reorienting without private investment.

Private finance takeover of established universities may be one effective way for large multinational venture capital firms to enter the sector. Pre-emptive rationalisation for such take-overs is already evident at some institutions, which are turning themselves into cheap degree shops. It stands to reason that we could see private take-overs, management buy-outs or convoluted group structures that include charities formed as subsidiaries of for-profit enterprises.

Stanfield suggests that five private equity companies were looking to take over “all or part of a UK university.” Besides total acquisitions, the cleanest solution according to Eversheds, are partnerships that could involve “research commercialisation projects, revenues from overseas campuses and from selling access to the institution’s degree awarding powers in the private sector.”

Many of these options were set out in a report that Eversheds produced for Universities UK back in 2009. Such private initiatives will reveal Anthony Grayling’s New College for the Humanities to be the sideshow it is: new UKBA regulations make the institution ineligible for ‘Trusted sponsor’ status and therefore unable to secure visas for non-EU students.

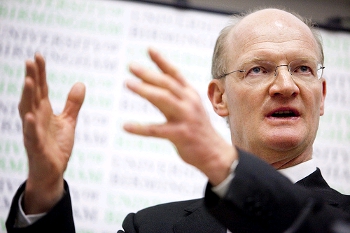

Even without such overt transformations, a shift in the balance of public and private money is not without consequences for institutions. As David Willetts, Minister for Universities & Science, recently confirmed, as state support to universities falls below 50% and since tuition fees count as private investment, EU public procurement rules will no longer apply to most universities as they will be considered to be private companies.

We have looked at the effects of recent bonds issued by the University of California. Maintaining an AA credit rating has led UC to ‘pledge’ its tuition fees to a bank account held by the trustee for its bondholders, Bank of New York Mellon. It has issued nearly $10billion of bonds since 2003 and tuition fees have raced to double what they were. Is this something we will see here as universities move from stable public funding to new private sources?

Willetts recently denied implementing a “scorched earth policy”, but the UK’s experience with privatisation has been very difficult to reverse and, has only been undertaken as a last resort (for example, with the case of the renationalisation of Network Rail).

Our ongoing research is motivated by the sense that the world of university financing is going to become an even more difficult place. Lots of our intellectual habits and our thinking about higher education will no longer be appropriate. This move has profound consequences for governance and democratic oversight.

With major legislation planned for Spring 2012, there is a need to start a debate now. How do we ensure that public interest is served when confronted with these forms of privatisation?

Andrew McGettigan will be speaking at Senate House on Friday, 14th October, at “Financialisation, Monetisation, Privatisation: Creating the New Market in Higher Education.”

Please read our comments policy before posting.

1 Comments