Canada has had three general elections in a row since 2004 where no party gained an overall majority, and no coalition government has emerged, as the Ottawa politicians have repeatedly failed to adapt their behaviours to changed voting patterns. Anne White considers the lesson for the UK.

Canada has had three general elections in a row since 2004 where no party gained an overall majority, and no coalition government has emerged, as the Ottawa politicians have repeatedly failed to adapt their behaviours to changed voting patterns. Anne White considers the lesson for the UK.

Like the UK, Canada has a first-past-the-post system electoral system, a Westminster-style parliamentary system, two top parties alternating in government (the Liberals and the Conservatives) and a strong Parliamentary majoritarian culture which has dominated government formation since the Confederation was first established in 1867. Of the forty federal general elections, thirteen have returned minority governments but these have tended to be short-lived, lasting an average of only 18 months.

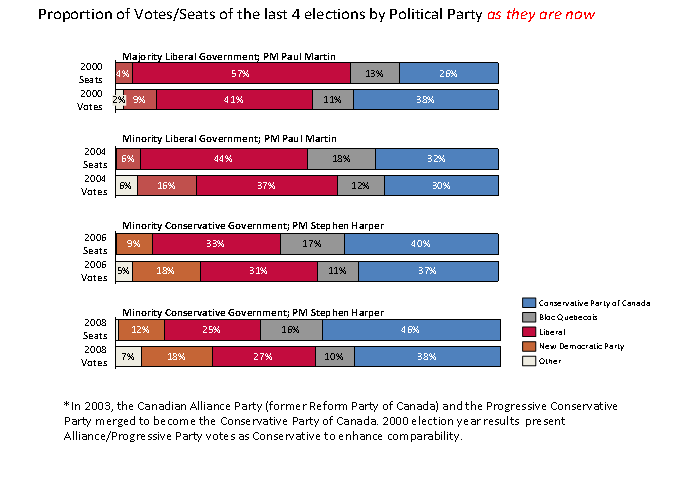

However, the most recent period of minority government began six years ago now and continues with the current Conservative government under PM Stephen Harper. This change may reflect the relatively recent presence of the separatist Bloc Quebecois in the federal parliament and their ability to capture the Quebec vote. It is now an entire decade since Canada last elected a majority government, as our Table shows. A Liberal minority government operated from 2004 to 2006, and a Conservative minority government since 2006.

Table 1: Election results of past four Canadian General Elections

Whilst some past Canadian minority governments are remembered as successes, the current period of minority government appears to have been largely seen as a failure by the media and voters. Canadians have grown weary of what they see as an uncooperative parliament and opinion polls now show a growing impatience with minority administrations amongst a majority of respondents.

Whilst some past Canadian minority governments are remembered as successes, the current period of minority government appears to have been largely seen as a failure by the media and voters. Canadians have grown weary of what they see as an uncooperative parliament and opinion polls now show a growing impatience with minority administrations amongst a majority of respondents.

However, this current reaction may have just as much to do with Prime Minister Harper’s characteristically high-handed approach to government than with his slight numerical advantage. Harper formed his first minority government on the cuff of a scandal about Federal Sponsorship, not unlike the UK’s recent expenses scandal, which saw the long-standing Liberal Party drop precipitously in the polls. With the main opposition party in disarray and looking for a new leader, the Harper government became emboldened and began to challenge Parliament to defeat it, at times passing controversial bills as confidence motions – knowing that the unpopular Liberals would choose to abstain rather than bring down the government.

In Canada, cooperation between the main parties has largely been a tool of last resort. Indeed, in December 2008, the Harper administration pushed the opposition parties so far on a vote of confidence that it faced certain defeat. However, the Canadian Governor-General (the Queen’s representative) made a controversial decision to prorogue Parliament for two months – providing a “cooling off” period for the opposition parties and the Conservatives to make the necessary concessions to achieve a more stable style of governance, None the less the episode left many Canadians disillusioned about elite manoeuvres and concerned about their ability to voice concerns in Parliament. More recently, Harper again prorogued Parliament in what appeared to be a move to prepare the Speech from the Throne (the Queen’s Speech) without interference.

The Harper government’s use of such strong-armed tactics to govern, and Canada’s weariness with the current administration, may both have more to do with the obsession amongst the media and leaders in both the Opposition and Government alike about the prospect of someone once again getting to win a parliamentary majority. Canadian politicians still see minority governments as a short-term and temporary inconvenience – even though the current situation has strong roots in modern voting patterns. The recently merged and reconstructed Conservative Party of Canada and the arrival of the separatist Bloc Quebecois on the federal scene are widely seen by analysts as shifting Canadian politics into a new pattern likely to endure for the foreseeable future.

The Parliamentary culture and media commentary continues to be more about an ongoing battle to “win” a coveted majority rather than a focus on achieving stable governance and policy – an experience that may soon be replicated in the UK. But, after six years of turf battles and the ever-present threat of the Prime Minister calling a new election to exploit some temporary polls advantage, evidence is now just beginning to emerge that Canadian voters would increasingly prefer a formal coalition to minority governance after the next general election.

Anne, there is no doubt that many politicians in Canada remain in denial about minority government despite increasingly diversified and volatile voting patterns. This came across loud and clear at a conference on minority government a few months ago at the Canadian High Commission in London where former politicians on the panel argued strongly against. Check my own comment on the subject on Matthew Shugart’s blog http://fruitsandvotes.com/?p=3928

Hello Anne,

I’m the UK reporter for Canada’s Global News. We are looking for someone who can comment on the British election and lessons from Canada’s minority governments.

Would you be available for an interview either today Tuesday, Wednesday or early Thursday?

Best Regards,

Stuart Greer

07765-871-770

Hi Anne, I enjoyed reading your article.

I’m worried that with five political parties (Liberals, Conservatives, NDP, BLOC, and the Green Party) operating at the Federal level we in Canada will not soon experience a majority government. Although, I feel a movement to unity the “left” would overcome this obstacle.

Minority governments (hung Parliament) make interesting news, while majority governments are just “snooze-fests.”