With a new government on the cards by this weekend, Anne White and Patrick Dunleavy consider what might change in Whitehall and the civil service

With a new government on the cards by this weekend, Anne White and Patrick Dunleavy consider what might change in Whitehall and the civil service

Reorganizing the structure of civil service departments is one of the easiest and most powerful tools at the disposal of UK Prime Ministers – and one they have rarely been able to resist using as soon as they come into office. New departments are a great way to signal political priorities to the electorate. They can refocus departments on new or emerging policy and administrative challenges, and look like they are fulfilling manifesto promises. They are a key way in which a PM can reorder the Cabinet, reward allies and favourites with bigger briefs. And, Prime Ministers in the UK can make these changes literally overnight, with little or no opportunity for parliamentary scrutiny either before the change happens, and not much more afterwards.

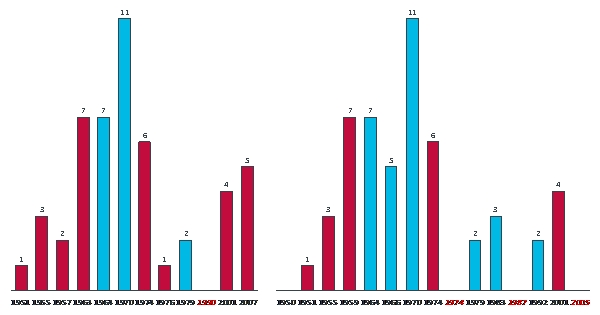

So it is not surprising that the vast majority of new Prime Ministers change the structure of Whitehall (Figure 1). In fact, only one new premier refrained from changing department configurations since 1950, and that was John Major in 1990 when he suddenly succeeded Margaret Thatcher at 10 Downing Street. Even Major later succumbed to the temptation to make his mark on the map of Whitehall after winning the 1992 election, when he created the Department of National Heritage and abolished the Department for Energy, merging it into the Department for Trade and Industry.

Figure 1: Number of Department Reconfigurations Post-Appointment and Post-Election (respectively) since 1950

Looking forward to this weekend, after the general election, we can be pretty sure that changes will be made with any new government. The Conservatives have been clear on multiple occasions that they would prefer not to tinker with the machinery of government: “There can and must be no distractions. Re-shuffling the administrative deckchairs would be a waste of time and energy” according to Oliver Letwin. Yet, oppositions often are more pious than they prove in government.

We expect to see at least one department level change – and possibly four in the first year, if a Conservative government is elected with a working majority, shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Possible Department Reconfigurations under a Conservative Administration

Department and Expected Change Type of change Scale of Change

Current Department of Health becomes Department of Public Health This is mostly a sub-departmental change involving the governance structure of the NHS, which will be further removed from political control by ministers. A Board of Governors for the NHS will handle most administrative issues, leaving the Whitehall department to follow the United States model and focus mainly on Public Health issues. Low in political terms, but huge in management terms

Current Department of Children, Schools and families becomes an integrated Department of Education once again, and loses responsibility for children’s services Universities and further education are taken out of BIS (Business, Innovation and Skills) and reintegrated with schools. Childrens’ services move out from DCSF to the new Department of Social Justice (see below) Low

Scottish Office, Welsh Office and Northern Ireland Office (NIO) are merged into one new department Currently the Scottish and Welsh Office roles have been getting thinner and thinner, and they are held by ministers with other departmental responsibilities. Merging them with NIO saves costs for two small departmental centres and may help the Conservatives look as if they are devolving power. Medium

A new Department of Social Justice is set up Intended as a vehicle for Ian Duncan-Smith the new department would take over childrens services, early years and family issues, perhaps drugs policy from the Home Office, and the voluntary sector and ‘Big Society’ briefs. This looks like a ministry that would not last long in Whitehall. Large

The most significant change which has been rumoured to occur would be the creation of a Department of Social Justice (or Department of Children and Social Justice). It is unclear at this time what shape such a department might take or whether a Council for Social Justice would suffice to generate more joined-up policy for welfare, family, early years, drugs and the voluntary sector. What is clear, though, is that bringing Ian Duncan Smith into Cabinet would be desirable for Cameron and a new department would seem to be the easiest way to accomplish this.

In forthcoming research to be published in the coming days by the Institute for Government, called Making or Breaking Whitehall Departments, we found that senior civil servants strongly feel that politically motivated changes of this type are the least likely to deliver concrete benefits in the short to medium term. New departments are also amongst the most disruptive changes to Whitehall. Our research shows that they inevitably create new costs of at least £15million a year. Usually civil service transition teams are forced to create a new department with little to no preparation time, in many cases having to function without proper accommodation, resources or support, while they bring the department together – all whilst continuing to deliver the existing services that the department has taken over. A Department for Social Justice would likely strongly experience all of these challenges, since the taks it would take over are currently located in many different silos and run by completely separate organixations at the local level.

The other parties have fewer rumoured changes. If Gordon Brown stays as PM, he has been in power for some time and we would expect department structures to stay pretty much the same – although he too might seek to consolidate the Scottish and Welsh briefs into one department centre. The real problems for Brown’s Whitehall concern the operations of Cabinet committees, which have multiplied and become more numerous and more complex than at any time in recent British history.

If Nick Clegg becomes involved in a coalition government – rather than shying nervously away as he seems all to likely to do – it seems that the Liberal Democrats might consider consolidating departments in Whitehall. This move would help create the appearance of savings and dramatize a resolve to push through public sector efficiencies.

However, any coalition government could produce new pressures on Whitehall organization – specifically to keep a relatively large Cabinet, so as to make room for 6 to 8 Liberal Democrat ministers while also minimizing the number of leading Labour or Conservative politicians who would have to move down a peg to make way for them.

The full report by Anne White and Patrick Dunleavy on Making and Breaking Whitehall Departments: A Guide to Machinery of Government Changes will be published by the Institute for Government in the next few days. To find out more about the ongoing LSE and IfG research go to: http://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/content/135/mergers-and-demergers-of-whitehall-departments

A very timely and interesting report. Shame that the new government appears to have followed precisely none of the sensible recommendations contained within!

I refer to the dismantling of the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) and the creation of a new Department for Education (DfE). By the end of the first day of the new government, signs had already been changed at HQ and even the website had a new DfE header.

Michael Gove, the new Education Secretary, has said that he wants to ‘refocus the Department on its core purpose of supporting teaching and learning’. So, families are out. Given that the current lot of Tories appear to be big fans of families, surely they will not want this policy area to fall by the wayside. So, should we expect a new Department for Families to re-refocus this policy priority?

The fact that the country had little idea which parties would even be in power up to the morning of this new departmental creation gives an idea of the level of preparation. Any sign of a 4-week preparation period? Apparently not. Any affirmative parliamentary resolution? Ugh…no. Any detailed assessment by parliamentary committees? Not likely. Any cost-benefit analysis? Yeah…right.

Maybe this kind of sweeping change is a reasonable prerogative for a new government. And the Tories have, after all, talked about the need to re-emphasize some basic objectives, like education, and move away from perhaps some of the more hyperactive reforms in the latter years under Labour. (What the hell happened to DBERR?)

Your report raises interesting questions around about how joined-up Departments actually need to be in order to achieve joined-up and integrated public service outcomes. You are right to point to more standardised approaches to reform. But should we also be moving to more ‘modularized’ approaches? Under such arrangements, core chunks of administration would be allowed continuity and stability over time, but would be much more ‘loosely coupled’ in such a way that they can be systematically moved around in order to encourage new synergies and innovation.