Residents of left-behind areas are often portrayed as part of a working class that views multiculturalism and liberal social attitudes as ‘alien and threatening’. However, in his research, James Morrison found that it was the economistic (underinvestment in schools, housing, the NHS, public transport, and jobs), rather than culturalist, diagnosis of ‘left-behind’ discontent that shaped the narrative adopted by newspapers and politicians.

Residents of left-behind areas are often portrayed as part of a working class that views multiculturalism and liberal social attitudes as ‘alien and threatening’. However, in his research, James Morrison found that it was the economistic (underinvestment in schools, housing, the NHS, public transport, and jobs), rather than culturalist, diagnosis of ‘left-behind’ discontent that shaped the narrative adopted by newspapers and politicians.

We’re all familiar with the stereotype of the ‘left-behind’ place: a post-industrial backwater marginalised as much by its cultural disconnection from ‘cosmopolitan and globally integrated Britain’ as political inattention or material disadvantage. In a slew of influential books, from Ford and Goodwin’s Revolt on the Right to Deborah Mattinson’s Beyond the Red Wall, the ‘typical’ denizens of left-behind areas are portrayed as an ‘older, less educated, disadvantaged and economically insecure’ traditional working class who regard both multiculturalism and latter-day liberal social attitudes as ‘alien and threatening’.

However, the framing analysis of press coverage and parliamentary debates I carried out for my new book on the discourse of ‘the left behind’ shows that, throughout the three and a half years separating the 2016 Brexit referendum from the 2019 general election, they were overwhelmingly identified as casualties of neoliberal economics – not protagonists in a simmering culture war. For all the Faragist attempts to co-opt hard-pressed working-class communities into a nativist uprising, by scapegoating foreigners for inequalities fuelled by global capitalism, it was the economistic, rather than culturalist, diagnosis of ‘left-behind’ discontent that shaped the narrative adopted by most newspapers and politicians – foreshadowing the ‘Levelling Up’ agenda to come.

Similarly, in interviews I carried out with parish councillors, community activists, and other residents of areas often tagged with the ‘left-behind’ label – from Doncaster to Rhondda – gripes about ‘woke’ liberal causes or immigration barely figured. On the rare occasions that anyone even mentioned the impact of foreign incomers, what worried them wasn’t the drowning out of British values but all-too-mundane pressures they blamed on decades of underinvestment – in schools, housing, the NHS, public transport, and jobs. Put simply, I heard very few moans about migrants but numerous rants about buses!

Press and parliamentary diagnoses: by what or whom are people left behind?

To break down the dominant characteristics ascribed to ‘left-behind’ communities during the life cycle of the Brexit referendum – the period separating the UK’s decision to leave the EU and the 2019 election that ‘delivered’ Brexit – I carried out a framing analysis of portrayals of ‘the left behind’ in press articles and Hansard records clustered around five snapshot periods encompassing key ‘discursive events’. Only the first four of these applied to Parliament, which was dissolved throughout the fifth. The snapshots were:

- 23 June to 22 August 2016 – the two-month period encompassing the referendum, then Prime Minister David Cameron’s resignation and Theresa May’s succession

- 29 March to 28 June 2017 – the three months from the activation of Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty (triggering Britain’s EU withdrawal) to the ‘snap’ general election

- 4 December 2018 to 3 February 2019 – the period during which Mrs May failed to pass her EU Withdrawal Agreement through Parliament; she survived two votes of confidence; and ex-UKIP leader Nigel Farage launched the Brexit Party

- 3 May to 2 June 2019 – the month encapsulating the Brexit Party’s victory and the Conservatives’ defeat in the UK’s final elections to the European Parliament

- 28 October to 27 December 2019 – the two months encompassing the snap election and Boris Johnson’s Queen’s Speech launching his ‘Levelling Up’ agenda

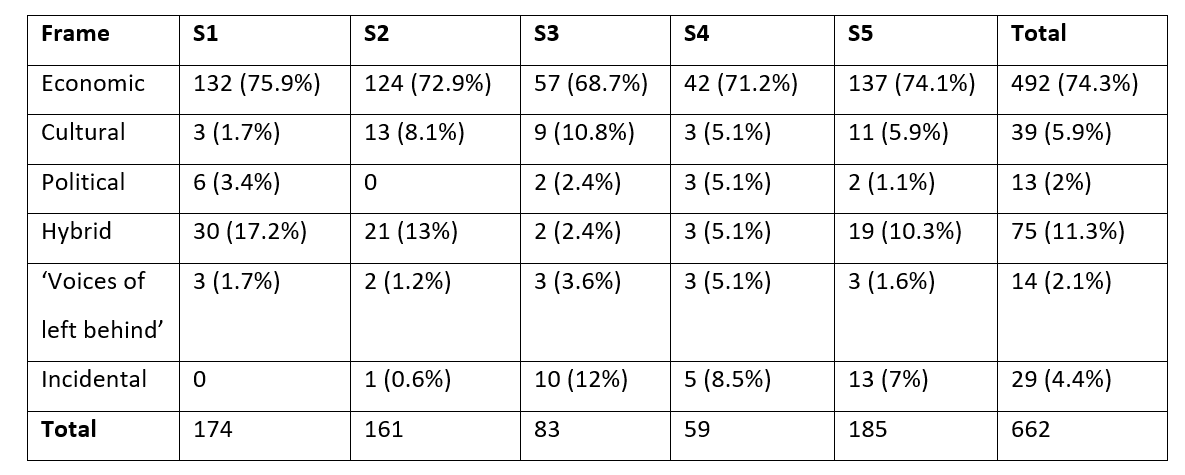

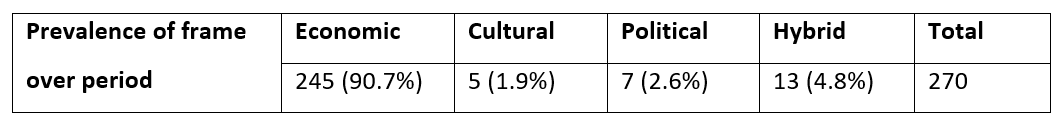

Altogether, I sampled 662 print and online newspaper articles from the Lexis Library database and 270 parliamentary records from online Hansard. Immersion in these datasets identified six newspaper frames of ‘the left behind’: as an economic, cultural, political or hybrid phenomenon; an ‘incidental’ subject mentioned in passing in articles about wider issues; and through vox pop-style pieces foregrounding the ‘voices of the left behind’. Only the first four frames applied to Hansard. As Tables 1 and 2 illustrate, nearly three-quarters of articles (492) and nine out of ten parliamentary mentions (245) framed ‘the left behind’ as economic casualties of globalisation. Although culturalist frames did occupy the second biggest category (after a hybrid one, combining aspects of both), they only accounted for 39 articles and five Hansard records in total. Meanwhile, just 13 articles (two per cent) framed ‘the left behind’ as politically marginalized – though this frame featured slightly more in parliamentary debates, pointing to a degree of concern among MPs and peers themselves about the question of whether such communities had been let down by policy and/or the political process.

Table 1: Breakdown of newspaper frames

Table 2: Breakdown of parliamentary frames

While culturalist framing was relatively muted overall, the trajectory it followed when it did surface was intriguing, as its level of visibility confounded events in the real world as often as reflecting them. It was almost absent during the first snapshot – surprisingly, given the heavily culturalist, anti-immigrant tone of some later pre-referendum campaigning, as symbolised by Nigel Farage’s notorious ‘Breaking Point’ poster. Conversely, the times when it moved the dial significantly were during snapshots 2, 3 and, to a lesser extent, 5 – all clustered around major democratic events that determined the future course of Brexit (the 2017 election, Mrs May’s Withdrawal Agreement defeats and the decisive 2019 ‘Brexit election’). In these latter cases, then, culturalist tropes became discursive touchstones at pinch-points when Brexiteers feared their dreams of leaving the EU might be thwarted.

The ‘left behind’ as culture warriors?

This brings us to the one realm in which culturalist representations of ‘the left behind’ did feature prominently throughout the sample period: social media. Tweets and newspaper comment posts published on the nights of the referendum and 2019 ‘red-wall’ election offered foretastes of sentiments that would underpin Boris Johnson’s ensuing ‘war on woke’ – suggesting that, below the line, culturalist debates were bubbling away, albeit largely among the self-selecting publics of partisan press echo-chambers and Twitter. While posters on The Guardian typically decried Labour for provoking a mass defection by working-class voters exasperated by its middle-class turn, posters on right-wing sites (The Times and The Sun) co-opted ‘the left behind’ as newfound fellow travellers in a backlash by an imagined cross-class ‘silent majority’ – united in its collective desire to liberate Britain from Brussels and other interfering elites. As so often, though, the most divisive debate unfolded on Twitter, with anti-Brexit/Tory posters increasingly castigating Leave-voting ‘red-wallers’ as the years passed. By election-night 2019, this sentiment was encapsulated in this despairingly abusive tirade: ‘I don’t want to hear any more about the “left behind”. You deserve to be left behind. Cretins’.

If there is one abiding lesson to be learned from the way ‘the left behind’ were debated during this uncommonly febrile period, then, perhaps it is this: while the mainstream media-political commentariat largely coalesced around an economistic diagnosis of their position, all labels are mutable and, as such, ripe for redefinition and appropriation. A key argument of my book is that the term ‘left behind’ morphed into a ‘floating signifier’ – allowing politicians and journalists of Right and Left to redefine and repackage it to suit their own ideological ends. Put simply, Conservatives/Leavers often imposed culturalist readings to distract attention from the economic drivers of ‘the left behind’s’ discontent, while some liberal-Left/Remainer actors could be accused of stigmatising them as culturally backward – or, at worst, racist. In the end, maybe terms like ‘left behind’ ultimately do more harm than good when it comes to characterising, let alone assisting, those whose (often legitimate) grievances they are meant to spotlight.

Note: The above draws on findings from the author’s new monograph, The Left Behind: Reimagining Britain’s Socially Excluded.

_____________________

James Morrison is Reader in Journalism at Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen.

James Morrison is Reader in Journalism at Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen.

Photo by jimmy brown, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence