The government’s three month consultation on plans for English schools is now coming to a close. While the Green Paper contains a variety of policies, the most high-profile proposal has been that of restarting the expansion of grammar schools. Carl Cullinane explains why, despite the attention, expanding selection will not lead to more good school places.

The government’s three month consultation on plans for English schools is now coming to a close. While the Green Paper contains a variety of policies, the most high-profile proposal has been that of restarting the expansion of grammar schools. Carl Cullinane explains why, despite the attention, expanding selection will not lead to more good school places.

The months since Theresa May first announced her plans to scrap the 1998 legislation banning the establishment of new grammar schools have seen a renewed and impassioned debate on academic selection in England. The government has indicated that new grammar schools are at the centre of their drive for more ‘good school places’ and greater social mobility. However, whether an expansion of selection is likely to lead to either of those goals is more questionable, given the evidence.

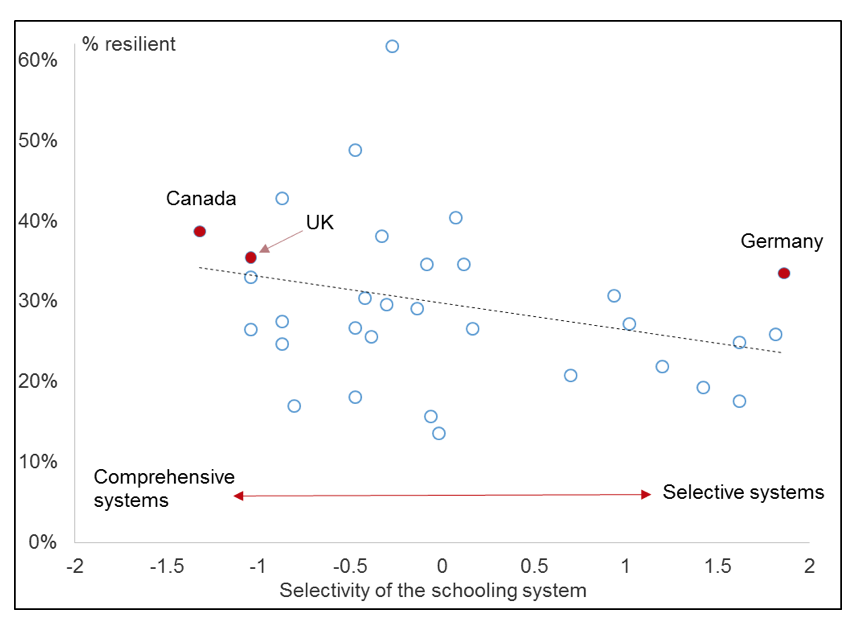

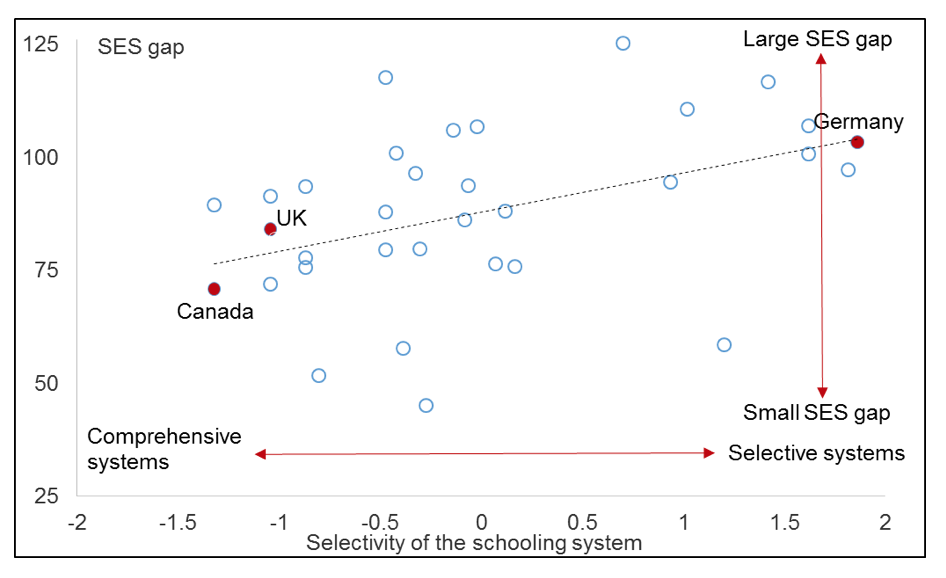

Just last week, the OECD launched their latest Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) report comparing 15-year-old pupils across 75 countries. Ministers have argued that the PISA results show evidence in favour of selection, yet the report itself shows that not only is academic selection not associated with higher performance by disadvantaged pupils, the opposite may be true. As figure 2 demonstrates, selective systems are also shown to have bigger gaps between rich and poor pupils and thus greater inequality. The overall report concludes that all types of pupils benefit from less selection, not more.

Figure 1. % of resilient (low socioeconomic background students achieving highly) pupils by selectivity of education system)

(Data available here)

(Data available here)

Figure 2. Socioeconomic status attainment gap in PISA by selectivity of education system

(Data available here)

(Data available here)

In England, the question of whether grammars facilitate social mobility is threefold: how many disadvantaged pupils get in to grammars, how do they fare when they do get in, and what effect does this have on children in non-selective schools.

Access to Grammar Schools

Studies consistently show that grammar schools are not taking their fair share of disadvantaged pupils. Just 2.5 per cent of grammar school pupils are eligible for Free School Meals, compared to around 14 per cent in all secondary schools, and close to 20 per cent in grammar school catchment areas. The government however has suggested they wish to expand the focus from disadvantaged children, to include ‘just about managing’ families (the now ubiquitous JAMs), who, despite largely being in work, find themselves squeezed by increased housing costs, bills, and stagnating wages.

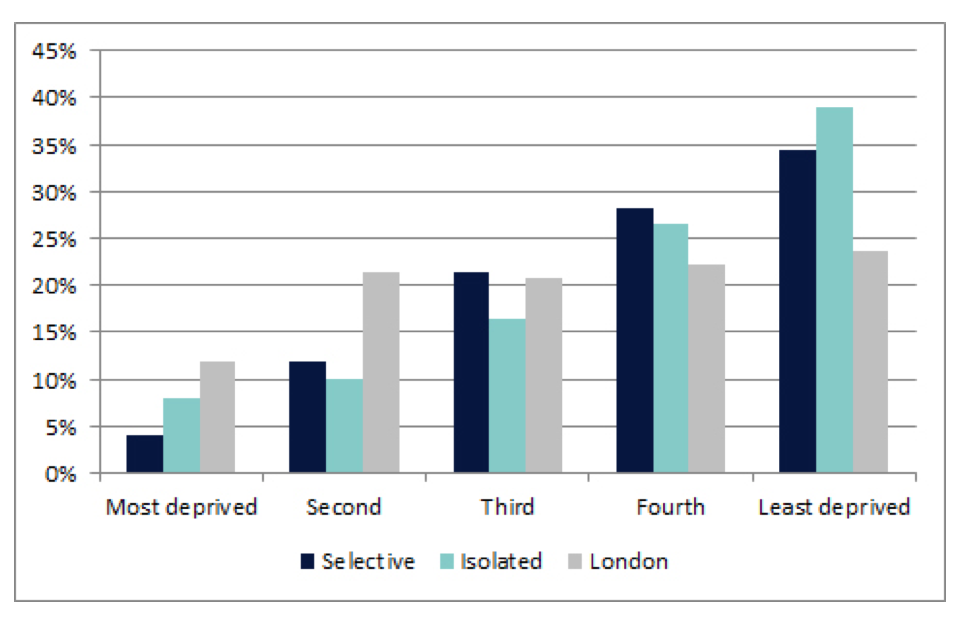

Grammar schools are framed as particularly helpful for the children of such groups. However, new Sutton Trust research indicates that the ‘just about managing’ also struggle to get into grammar schools, and are, in fact, not much more likely to attend grammar schools than the poorest families. Research combining Resolution Foundation work on JAMs and the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index, shows that ‘just managing’ families tend to live in neighbourhoods in the bottom two categories in figure 3 below, which, outside London, shows a steep gradient in access to grammars across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Figure 3. Proportion of Year 7 pupils in grammar schools by deprivation quintile

Living in a neighbourhood in the bottom two quintiles means pupils are substantially less likely to attend a grammar school. Importantly, multivariate analysis shows that this relationship holds even for non-disadvantaged pupils in those areas, and also controlling for prior attainment. This gives a strong indication that England’s grammars are not catering for JAMs.

While the King Edward VI schools in Birmingham have shown it’s possible to admit high proportions of disadvantaged pupils (up to 20 per cent) and Kent County Council has announced a willingness to move in that direction, other grammars have a long way to go in improving their intake of pupils from less advantaged backgrounds.

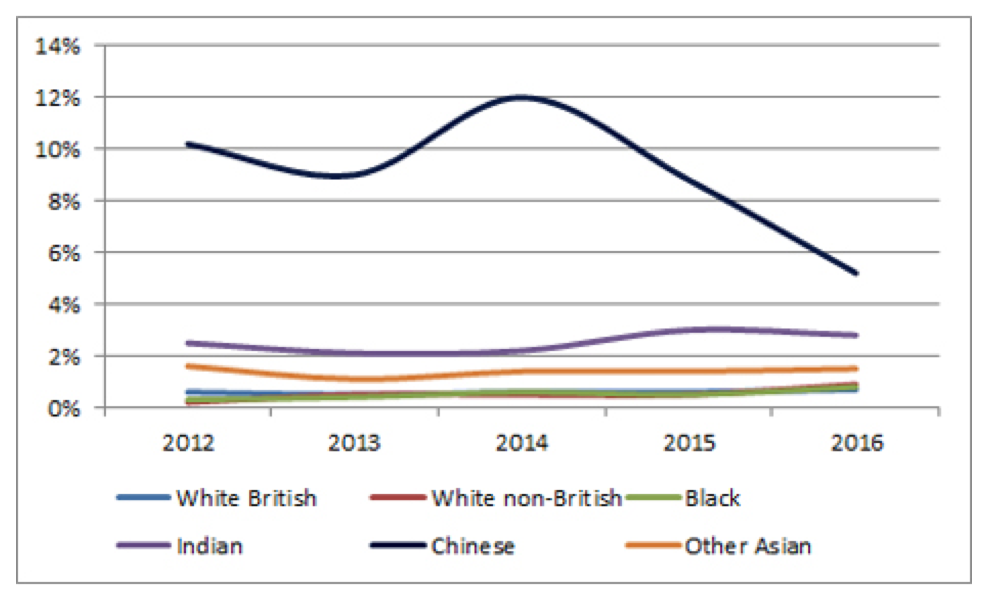

The likelihood of attending grammars also varies substantially by ethnic background. Recent research has demonstrated the poor attainment of white British kids, and similarly, we find that disadvantaged white British children enter grammar school at the lowest rate of any major ethnic group. Disadvantaged Indian pupils are four times more likely to attend a grammar than disadvantaged white British pupils, and disadvantaged Chinese pupils fifteen times more. While there have been modest increases in the rate of grammar entry for disadvantaged black children (from 0.3 to 0.8 per cent) and white non-British (0.2 to 0.9 per cent) over the past five years, the rate of white British entry has remained stagnant.

Figure 4: Proportion of FSM-eligible pupils entering grammars by selected ethnic groups 2012-2016

Attainment

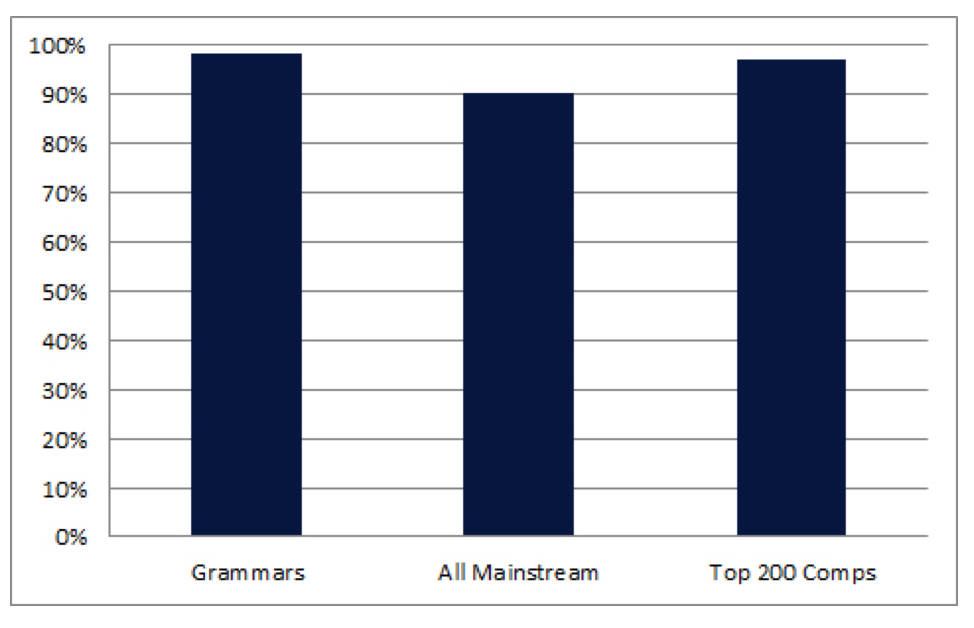

Parents and policymakers alike tend to be attracted to grammar schools because of their unquestionably high results. However, when you look more closely beyond the raw scores, this becomes significantly less clear. A variety of studies have shown that much of the advantage of grammar schools is explainable by the fact they admit pupils who are high achieving in the first place. This is true both for disadvantaged pupils and pupils as a whole. Expanding selection therefore has no guarantee that new grammar pupils will start performing better than they otherwise would. Figure 5 also shows that high attaining pupils do just as well at top comprehensives as they do at grammars, with 97 per cent of high attainers at top comprehensives achieving five good GCSEs, compared to 98 per cent in grammars.

Figure 5. Proportion of high attainers achieving 5 A*-C GCSEs (including English and Maths)

Finally, there is the vexed issue of the effect that grammars have on surrounding schools. The research is mixed on this issue, with a widely cited 2008 Sutton Trust report indicating that, in the country as a whole, there was no evidence that non-selective schools were negatively affected. However, recent indications are that, within the UK, areas with the highest concentrations of grammar schools have lower attainment in surrounding schools. Furthermore, this is particularly true for disadvantaged pupils, suggesting grammars may give with one hand and take away with the other.

It is therefore questionable whether increased selection would lead to more good school places overall, rather than to a concentration of previously high attaining students and high quality teachers in a small number of schools, with others suffering in comparison. Ministers rightly want to tackle the issue of low attendance of disadvantaged children at top universities. However, a better way to do this may be to boost the attainment and aspirations of highly able pupils across all comprehensives throughout their secondary education. The best candidates for support are not necessarily those that reveal themselves in the 11 plus.

Ultimately it’s clear that, despite the claims, grammars are no quick fix for England’s social mobility problems.

_____

Note: A shorter version of this piece was published on the Sutton Trust blog.

Carl Cullinane is a Research Fellow at the Sutton Trust. He previously worked as a statistician in NatCen Social Research and as a researcher in Democratic Audit UK. Carl holds master’s degrees from Trinity College Dublin and the London School of Economics.

Carl Cullinane is a Research Fellow at the Sutton Trust. He previously worked as a statistician in NatCen Social Research and as a researcher in Democratic Audit UK. Carl holds master’s degrees from Trinity College Dublin and the London School of Economics.

Thank you for this vital information.

The self evident truth about Grammar schools is that it has nothing to do with promoting better education but the rule of divide and conquer.

This is the 21st century and yet people have not learned that policies should be based on factual evidence such as this… I well understand that the politicians promoting this are more concerned with maintaining the status quo and creating a blame culture that castigates the victim for the disadvantages they in fact create, but people themselves are enabling this form of doctrine by looking for personal self gain which in the long run works against them and only serves the interests of the minority.

Education has been dominated by political forces that use it as a means of social control, not as they proclaim in the interests of progress, in fact it does the exact opposite, it ensures a small elite retains power and control of the masses, the dogmatic views of the Etonians in parliament demonstrate that a so called better education doesn’t produce more able or better people. Boris Johnson of late and David Cameron who consistently lied in parliament. Example: “There will be no top down reorganisation in the NHS”, only to preside over the deliberate and complete disorganisation of the NHS.

Education has always been regarded as a means of personal advancement, instead of enabling individuals to pursue a direction of their choice, the criteria for this has been set by the ruling elite to advance wealth and power back to them in a constant stream, division among the masses has enabled that to happen. Whilst the masses all fight among themselves for the crumbs thrown their way, the rich get on with the job of getting richer without regard to the chaos of their making.

The key to the success of this punitive system has been the financial control over people, in order to climb the slippery pole of success, people must demonstrate that they adhere to the norms expected of them by a tiny elite, all power is migrating into private hands which dictate the standards and reward those financially that serve their purpose.

In short we must all sit around waiting for multi millionaires to decide that they can get even richer by exploiting our talents. Money talks.

The reality is that democratic governments such ours do not have to do that and can act independently of large corporations and financial institutions…. can create jobs, public services, and spend into the economy when and where it is needed.

But the political agenda has been to promote poverty as a direct policy, which serves the interests of this tiny corrupt elite. Banks make money out of debtors and debt is how money is created, that is the vicious circle that has impoverished the world and that is what the mega rich wish to continue.

Which is why they don’t want to educate the masses.

If the Grammar schools were as they were when political ideas were imposed rather than educational the answer would be yes because anyone could go to Grammar school as long as they had the educational ability, but the idea that mixing the educationally challenged with the educationally gifted was wrongly accepted meaning that the educationally gifted were denied the education they needed and the the educationally challenged remained educationally challenged. Todays Gramma schools re basically somewhere between the public schools which cost a fortune and comprehensives, you need money to go to them.