In the event of a second leadership contest win by Corbyn, a ploy to split Labour’s parliamentary rebels using the Co-operative Party and its presence in Parliament has been suggested. Outlying the history of the relationship between the two parties, Sean Kippin argues that keeping the faith with Labour might be the Co-op Party’s best bet, given past experience.

In the event of a second leadership contest win by Corbyn, a ploy to split Labour’s parliamentary rebels using the Co-operative Party and its presence in Parliament has been suggested. Outlying the history of the relationship between the two parties, Sean Kippin argues that keeping the faith with Labour might be the Co-op Party’s best bet, given past experience.

Jeremy Corbyn’s probable romp to victory over Owen Smith in the latest Labour Party leadership election has raised the spectre of the party splitting in two. This scenario would see the ‘moderates’ (with most of the Parliamentary Labour Party) going one way, and the ‘socialists’ (with much of the membership) going the other. But Labour, still scarred by the memory of the 1980s and the breakaway Social Democratic Party (SDP), are understandably reticent to countenance splitting the main opposition party in two – a move that would likely further entrench Conservative dominance. Roy Jenkins famously (and ironically) predicted that ‘a social democratic party without deep roots in the working class movement would quickly fade into an unrepresentative intellectual sect’. However, some have mooted that Labour’s discontents need not form a new party, but instead reinvent an old one which does have deep roots into the working class: the Co-operative Party.

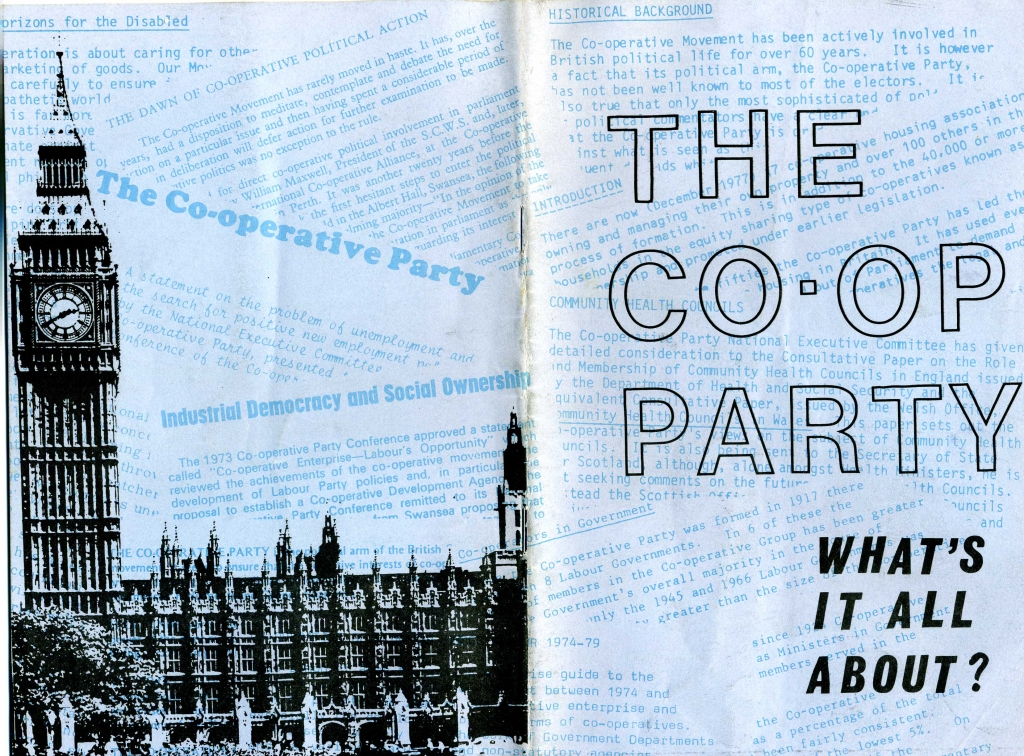

Founded in 1917, the Co-op have been partnered with Labour since 1927 and maintain a presence in parliament, local government, and the devolved assemblies. It promotes mutual and cooperative ownership, equality, and a broadly associationalist politics. Yet for Labour, organisational and ideological factors combined after 1945 to minimise the role of mutual and cooperative ownership in its policy prospectus, with state ownership and nationalisation becoming a key feature of Labour’s policy offer and latterly its political identity. It has been argued that this was an historic missed opportunity; had Labour embraced mutual and cooperative ownership – either as an alternative or supplement to state ownership – the global shift towards markets and away from the state may not have impacted upon it – and the working class communities it has traditionally represented – in quite the same way.

The current plan is, reportedly, to build upon the Co-operative Party’s status as a grouping within Parliament, bolster their ranks with anti-Corbyn Labour MPs, and use it to run an alternative opposition. The Co-op has rejected the notion, with its General Secretary Claire McCarthy stating that “the party [is] not a vehicle to be used by one political faction or another to advance their own agenda,” continuing that “[…] the Co-operative Party NEC has had no discussions about changing the way the Party operates based on the outcome of the Labour Leadership contest.” It has even been described in the Financial Times as attempted “Entryism” with the loaded connotations of that word on display for all to see.

But would the party be wise to reconsider this position? If a rupture in Labour were to take place, the Co-operative Party could gain a more prominent role, and attempt to reinvent Labour in its own image. Perhaps the Co-operative Party could rename itself the “Co-operative and Labour Party” and insist that mutualism is put at the centre of its political and policy approach, combining the left’s preference for increased use of cooperatives in the private sector, and the Blairite right’s preference for an expanded use of mutualism in public services.

Reversing the historic shift towards national ownership that saw Labour reject mutual ownership, and creating an avowedly mutualist party must, at the very least, be tempting for both the Co-op Party and the movement it represents. Labour is performing poorly in the polls, and despite the unhelpful ‘optics’ of a coup and chaotic second leadership election, the party does not look on the cusp of a return to power, even if the ship steadies after Corbyn’s likely victory. If the Co-operative Party decide that Labour is to cease becoming a viable party of government, what exactly would it have to lose?

The Co-op Party, has of course been here before, and had it acted differently it could have indeed lost lots. During the period of turmoil which engulfed Labour following its loss of power in 1979 the Co-op saw both it and its policy agenda sidelined in favour of battles over nationalisation and internal party politics. The Co-op lost four of its seventeen MPs to the new SDP, including Dickson Mabon, the party’s only Privy Councillor and a former Minister of State. At the 1983 election, the party was reduced to just seven MPs. So great was its marginalisation, and the defections to the SDP, that journalists took it at face value that the party would end its historic link with Labour and defect wholesale to the new insurgent party.

That didn’t come to pass. Partly because the Co-operative Party under the Secretaryship of David Wise worked to skilfully maintain the link with Labour out of both loyalty and because it was seen as the most effective way of realising the priorities of the cooperative movement. This was despite the legacy of earlier conflict within the Co-operative Party between those like Tony Benn who wished to use cooperatives as a way of preserving unprofitable industries, and those who wished for cooperatives to be competitive.

The decision to stick with Labour was eventually vindicated. Not only did Labour begin to rebuild quickly from the 1987 election onwards, the Co-operative Party began to have more of an influence over Labour Party policymaking, thanks to some thoughtful and well received policy work such as the Co-operative View of Socialism, the Co-operative View of Local Government and the Co-operative Agenda for Labour. These laid the groundwork for a successful partnership with the Labour Government of 1997, culminating in the New Mutualism project, which sought to influence the Third Way, and saw a Co-operative imprint left on policies such as NHS Foundation Trusts, the creation of Supporters Direct, and the development of the Co-operative Trust School model.

Since the election defeat in 2010, the Co-operative Party has increased the numbers of cooperators in Parliament, it has been a considerable influence over Labour’s 2010 and 2015 manifestos, and ran several high-profile campaigns – most notably to re-mutualise Northern Rock before it was sold to Richard Branson’s Virgin Money, and to mutualise National Rail. Over this same period, the Liberal Party and the Social Democrats merged to form the Liberal Democrats. Their inability to trouble Labour’s status as the main party of the centre left perhaps explains their drift to the centre-right under Nick Clegg, who eventually ended up in coalition with the Conservatives between 2010 and 2015. As a direct result of its decisions, the party has been reduced to a rump in Parliament, with fewer MPs than the Co-operative Party has now. A Co-operative infused SDP may have fared better, but the evidence doesn’t support the proposition that the Co-op made a mistake in sticking with Labour.

The current situation facing Labour is as serious as in the 1980s, but the debate has now turned to using the Co-operative Party as a vehicle for the continuation of what was mainstream Labour, and in doing so presumably breaking the 89-year-old partnership between the two parties.

Wisely, the Co-op have resisted taking this path. There are logistical as well as strategic issues that prevent this from being a good idea. For one, the Co-operative Party’s funders and affiliates are unlikely to have any appetite for an extended bout of internecine warfare, and given that recently the Co-operative Group held a contentious vote on whether to maintain the link with the Co-operative Party, it is possible that the link could come into question again. Naturally, the party will be keen to avoid that. Additionally, there is a degree of ideological polarisation within a Co-operative parliamentary group that ranges from Kate Osamor on pro-Corbyn left to Jonathan Reynolds on the neo-Blairite right which might threaten the coherence of any such grouping.

It should not surprise us that the Co-operative Party plan to keep the faith; all Co-operative political representatives also represent Labour, and most members of the former are members of both. It is that tribal loyalty which will likely sustain Labour whatever the outcome of the election, and a distinct but similar loyalty and bond will sustain the relationship between the Labour and Co-operative parties, and thus the wider movements that each respectively represents. Additionally, with a potential early election looming, Labour could be shot of Corbyn soon enough – particularly if the rule that leadership candidates require to be nominated by 20 per cent of the Parliamentary Party survives the current regime.

Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership may not represent an imminent return to government for the two parties, but waiting it out and hoping for a better tomorrow almost certainly remains the Co-operative Party’s quickest route back to power.

____

Sean Kippin is a PhD Student at the University of the West of Scotland, where he studies the influence of mutualism over the 1997-2010 Labour government. He was previously the Managing Editor of the LSE’s Democratic Audit blog, a Researcher for two Labour MPs, and is a Research Associate of the LSE Public Policy Group.

Sean Kippin is a PhD Student at the University of the West of Scotland, where he studies the influence of mutualism over the 1997-2010 Labour government. He was previously the Managing Editor of the LSE’s Democratic Audit blog, a Researcher for two Labour MPs, and is a Research Associate of the LSE Public Policy Group.

So we join the co-operative wait until the democratically elected leader of the Labour Party loses the next election, then we rise like a Phoenix from the ashes.

Which policy or policies of Jeremy Corbyn’s is the party not supporting exactly.

Or are we going down the line of whatever the media says is correct.

Would it not be good idea to get behind the leader and try and win the next election or does that not fit in with the co-operative party’s grand plan.

I prefer a true blue Tory to a blue Labour supporter.

Fascinating insight into current party politics. For future coop strategy, the big opportunity is elsewhere: a coop and mutualist vision for the gig-heavy 21st century. Generations XYZ are unconscious mutualists, but the movement can only connect with them by starting with a fresh piece of paper and no left-right blinkers…