Sir Robert Worcester is a Visiting Professor of Government at LSE and an Honorary Fellow. He founded MORI in 1969.

Sir Robert Worcester is a Visiting Professor of Government at LSE and an Honorary Fellow. He founded MORI in 1969.

The election has been static before Thursday’s debate; now it’s electric. Then the Liberal Democrats were a side show. Now they are centre stage. The LibDems are not going to win this election, but Clegg won the debate, hands down.

He had little to lose, much to gain, and he knocked it for six. Calm, cool and collected, it’s a wonder he didn’t turn to David Cameron at the end to say: “David, you were the future once.”

I said in my Analysis last week that there were three ‘wild cards’ left to play up to May 6th. The first debate “will be crucial”. The other wild cards the impact of the money pouring into the ‘Battleground States’ by the Conservatives, especially the Tory-Labour marginals in the 5 per cent-10 per cent swing needed to win over constituencies now held by Labour. The other wildcard is the turnout on the day.

Nick Clegg’s win has affected both. Up to Thursday there had been 18 national opinion polls, all 18 had the Tories at 38 per cent plus or minus two percent, static. All but three, the new boys on the polling block, had Labour’s share at 31 per cent plus or minus two percent. All but one had the Liberal Democrats at 20 per cent plus or minus three percent.

There are four stages of political communications: awareness, involvement, persuasion and action. Before Thursday’s debate Clegg had very low awareness, and now he’s the star of the show. Since the Liberal Democrats were not going to win, they were a turnoff. The electorate hadn’t really been listening to what they’ve been saying. Prospective voters want to know what the government is going to do for (or to) them and their families, and since they’d written off the Liberal Democrats, they were just not involved with them.

Now prospective voters are listening to Clegg, as they have been to what Vince Cable’s had to see about the economic situation. They’re now be ready to listen to persuasion from Nick Clegg.

With these things going for them they may well increase their number of seats, and in a hung parliament, which looks after the debate increasingly likely, and be more of a force in the land. It will be however a monumental task.

As I said in my weekly Analysis column in the Observer today:

“If the Tories have a mountain to climb, the Liberal Democrats are looking from the base camp to Everest. They have 63 seats in the House of Commons now. [Looking at several different seat translation models (‘swingometers) assuming a uniform national swing as a starting point] A 1 per cent swing would bring it to 68 seats, 2 per cent to 78, 3 per cent to 97 (where they are on the YouGov [now also ComRes figures] today), 4 per cent to 121 seats, 5 per cent to 154 seats, 6 per cent to 197, 7 per cent to 250 seats where they just might be the largest party, 8 per cent to four short of the 326 needed to be the majority party.”

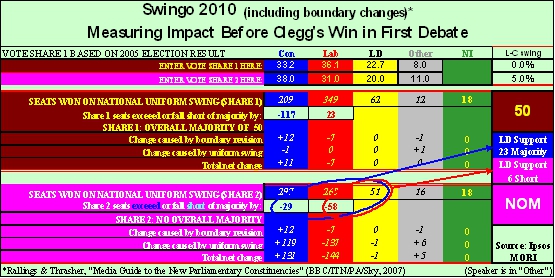

Looking at the average of the 18 polls since the Prime Minister’s announcement of the date of the election, May 6th, a month before, as noted above, the polls have been, until now, stable at 38 per cent for the Conservatives, 31 per cent for Labour, 20 per cent for the Liberal Democrats. Chart 1 uses Dr. Roger Mortimore’s ‘Swingo’ model, which is one now of scores available on the internet but when first invented by Roger, my co-author now of three, going on four, books after each election since “Explaining Labour’s Landslide” on the 1997 election, it was one of the first.

On the pre-debate consensus of the standing of the parties, neither the Tories nor Labour would command a majority over all other parties in the House of Commons. The Tories (on a uniform national swing – UNS – of 5 per cent) would be around 30 short of the 326 they’d need to have a majority. Labour’s hole would be even deeper, as they’d be around 60 away from the magic number.

With the support of the Liberal Democrats however, David Cameron’s 300 or so seats would be home and dry, with a majority of over 20. Labour would in contrast be a tad short, perhaps by from five to ten seats, even if they did get support from other parties in addition to the LibDems. Besides, Nick Clegg has made clear that he’s first look to the party leader with the most seats as a result of the people’s votes at the election. There’s also support for the Conservatives waiting in the wings, in addition to the half dozen Ulster Unionists they can count on.

Chart 1

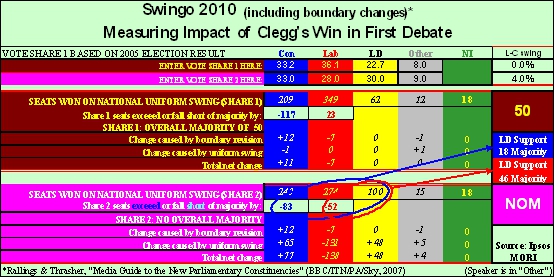

Looking then at the impact of Clegg’s win in the first debate, shocking as it was, would drop the swing to 4 per cent, and have the perverse effect of putting Labour in position to negotiate, being about 50 seats short, but around 30 ahead of the Tories. In either case, the major parties would try to struggle on, but some deal would have to be struck during the weekend after the election, as to leave it in limbo until the stock market opening Monday morning would give a field day to currency speculators, and jeopardise the pound sterling and cause further damage to the economy. Even with a 30 per cent share, the Liberal Democrats would only gain around 40 seats to add to the 63 they currently hold. (Chart 2)

Chart 2

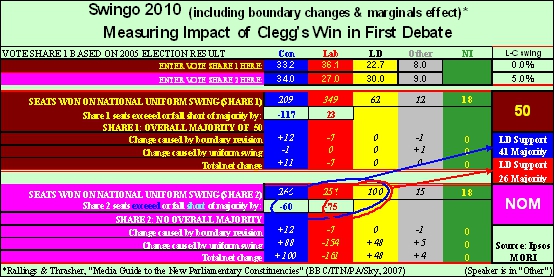

If the Ashcroft money is worth what’s been spent in the Tory marginals, and the jury’s out on that, it looks to be making a maximum effect of a one point swing. The Ipsos MORI research in the 54 Tory-Labour marginals where the swing that would be needed to put them into a majority is by our calculation a bracket from 5 per cent swing to 9 per cent. If then you put one point onto the Tory share, and deduct one point from Labour’s, it would give the Tories an overall majority and make Ashcroft feel his money had been well spent. (Chart 3)

Chart 3

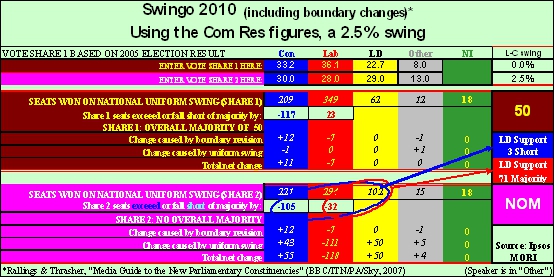

The ComRes figures are the real nightmare scenario for David Cameron, with over 100 seats away from a majority for his party. Even with over 100 MP’s votes, they’d need the Ulster Unionist’s votes to get just over the 326 majority, and it would be a most fragile alliance, even if it could be cobbled together (which in my view it can’t be). In this situation, I suspect you couldn’t get Gordon Brown out of Number 10 with dynamite, and he would struggle on with a minority government, and we’d have another election in 2010, not probably in just a few weeks, but certainly by the autumn.

Chart 4

But there’s 18 days to go, ‘miles to go before I sleep’. And there are two more debates, next Thursday and the week after.

Remember Nick, as Harold Wilson famously said to me when I was doing his private polling forty years ago, “a week is a long time in politics”.