For the first in our new series of short films we introduce the theme of walkability in London. As increasing groups of citizens press for more sustainable forms of transport and the GLA through the London Plan is set to give increasing priority to pedestrians over cars, walking as a form of transport has gained prominence. Given the need for social distancing during the COVID-19 crisis in a city that has seen the highest age-standardised mortality than any other region in the UK, walking will form an important part of any mobility strategy in the coming months. Responding to this new video, RUPS Alumni Mailys Garden (Principal Consultant at Momentum Transport Planning) revisits two projects in which walking was a particular feature.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Since becoming an urbanist (and probably before then too!) I’ve been interested in how we contribute to cities being at a human scale and the role that pedestrians play within them. I’ve been hugely influenced by Jan Gehl’s work, and having started my career in pedestrian planning and modelling, I realised that the way to help with crowding, and to make cities more walkable, was to make more space for people.

There are, of course, many ways to do this (and they need to work together) but one way is to re-allocate space away from motorised traffic. Alongside a team of very talented people at Momentum Transport Consultancy, my current role is to devise access strategies that win that space back for pedestrians.

We’ve recently worked on two examples of this approach which illustrate the role a transport planning consultant can play in contributing to making London a walkable city: the first, a strategy at masterplan level and the second, a strategy at building level.

Example 1: Masterplan strategy – Olympia Exhibition Centre (London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham)

Olympia, in West London, is undergoing massive regeneration. As part of the current operations, exhibitions and events tour nationwide and bring goods back to the estate to display – generating traffic, as well as large amounts of pedestrians for the most popular shows. The estate has developed over time, and traffic generated for the Exhibition Centre is spread across different areas of the estate.

Olympia Way pedestrianised. Visualisation courtesy of Yoo Capital

Challenges and opportunities

This created both challenges and opportunities for transport planning. One of the major issues we identified was traffic congestion – but one of the main opportunities was that we could increase public space.

In close collaboration with the design team, the proposal emerged to pedestrianise the main access road into the estate. Removing existing exhibition-related traffic from the adjacent highway network and providing 2.5 acres of public realm to serve the wider range of uses which will be introduced on site.

This meant re-thinking the access strategy for vehicles servicing the estate.

Other opportunities were to add new, complementary land uses to the exhibition centre, so as to strengthen its position as a national destination for the next 100 years and beyond. As a result the regeneration project also comprises a live music and performance venue, a theatre, hotels, office space and retail space. And this was unlocked by creating a unique logistics centre with access to the different parts of the estate.

Then what?

Achieving these two objectives required us to undertake many rounds of complex data analytics in a number of areas including: numerous surveys and observations to identify key pedestrian links; extensive traffic modelling; parking surveys; station modelling; and pedestrian comfort level assessments. Design iterations and operational models, case studies and benchmarks and vehicle movement analytics were completed to understand how to design and define the space requirements for the logistics centre. We also needed to understand the predicted impact of the regeneration scheme in terms of deliveries and waste removal and to ensure the site is car free (with the exception of blue badge holders). We worked closely with Transport for London and the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham to understand the impacts of closing the main access road.

With our analytics completed, we turned our attention to designing the public spaces and landscaping, all whilst keeping in mind the concept of competing needs such as cycle parking, greenery and places to sit – using TfL’s Healthy Streets approach to help manage different requirements.

And finally, more testing and more pedestrian modelling to review different scenarios and understand the performance of the space, and strategies to improve future visitor access to the site both during and after construction.

Where we are now?

The proposals were approved by committee in January 2019 so now we need to build it! During this time, it’s essential that we continue to consider pedestrians going to and from the estate, as well as those using the footway network surrounding the site.

Example 2: Building strategy – One Leadenhall (City of London)

One Leadenhall is a 36-storey tower providing more than 500,000 sq ft of prime working environment in the heart of the financial centre of London and 50,000 sq ft of shops and cafes on a podium in the first floor of the tower. With very significant levels of development in the immediate surroundings of the site, and being located adjacent to some of the busiest streets in London, construction logistics was a major challenge. But it also created a key opportunity for collaboration and to win back space to make the area more walkable.

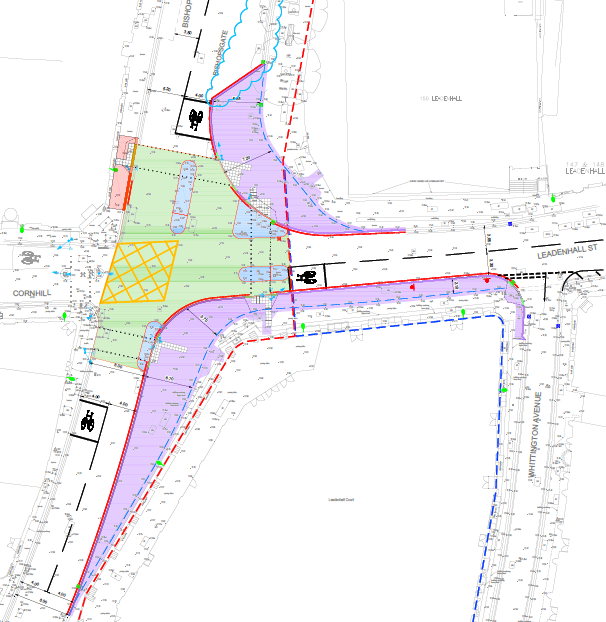

Design of a narrower junction at One Leadenhall to help construction logistics and increase space for pedestrians. Sketch by Momentum.

Challenges and opportunities

One of the key challenges at the outset was another building, also under construction, which shared the same junction as One Leadenhall. The joint objective became to create a cohesive approach for pedestrians and cyclists, which would maintain consistent pedestrian access – as well as consistent traffic management – throughout the works and beyond.

Then what?

We developed the detailed design for a temporary highway scheme for the shared junction, and a suite of construction logistics plans to enable construction to proceed whilst minimising the impacts on other users – in particular pedestrians.

It became apparent as we developed the construction logistics strategy that a physical change to the road junction and footways would significantly simplify the construction arrangements, whilst providing a more consistent and much improved environment for pedestrians that avoided the need for footway closures. We undertook pedestrian studies to analyse the current and future pedestrian demand in the area to demonstrate the benefits of the scheme in line with both City of London and Transport for London requirements.

By making the junction smaller and maximising the kerb space all development works could be carried out safely and efficiently, while still creating more space for pedestrians. By changing the junction, we were also able to remove a sub-standard alignment through the junction that created potential safety issues for cyclists.

Alongside the construction logistics work, a freight consolidation strategy proposed for One Leadenhall (once completed) will reduce vehicular impact and maximise public realm space for office users and city dwellers.

Where we are now

Planning consent for One Leadenhall was approved in January 2017 and the junction changes were implemented last year in anticipation of the start of demolition and construction in 2020.

The additional space for pedestrians on the surrounding footways is immediately apparent when visiting the space. There is acknowledgement from TfL and CoL that the revised junction is beneficial not only to facilitate construction, but can also provide a long-term solution for the benefit of sustainable transport modes in the area. As such, the new junction is now also operating as a test case for a final scheme junction over the four-year construction period.

Undoubtedly, the dual benefit observed in achieving improvements to the construction logistics approach for two major schemes in the City through constructive and open collaboration between two developers, coupled with the opportunity to trial a new junction layout that will reallocate space away from motor vehicles and to pedestrians long after the construction works are completed, constitutes a real value added for the area.

In summary

Both of these projects highlight that integrating all aspects of transport consultancy – analytics, engineering and transport planning – can play a huge role in making the city more walkable from both masterplan and building strategy level. And most importantly they clearly demonstrate that reassessing existing conditions and reallocating space towards sustainable transport – to the huge benefit of the people using those spaces – is entirely possible.