Cities all over the world are at the forefront of climate change. To tackle the crisis, planners and urbanists are coming up with innovative solutions – one of them is to use behavioural psychology to better our relationship to public transport in the city. In this video, Emma Sagor (Portland) and Elaine Trimble (London) explain how behavioural science has informed their transportation projects. Emma Sagor further explains the role of behavioural science in climate action planning in the post below.

Planners: Natural Soldiers in the Climate Crisis Fight

Every day, planners witness the intertwined nature of urban society first-hand. Housing development impacts transportation and mobility. Mobility impacts economic growth. Economic growth impacts energy consumption. Energy consumption impacts natural resources. And on and on. Being an effective planner requires us to understand these cross-cutting dynamics—and help our communities plan accordingly.

When it comes to combatting the climate crisis, arguably the existential threat of our time, this intersectionality is even more critical. Every plan we develop in each of these sectors has the potential to accelerate or mitigate climate change, while in turn, rising global temperatures threaten our housing, transportation, economic, energy and natural systems. In short: to do good planning, we must tackle the climate crisis. But to tackle the climate crisis, we’re going to need good planning.

It was this realization that led me to apply my planning skills to the climate fight. I currently work as the Climate Advisor for the City of Portland, Oregon, through the Bloomberg Philanthropies American Cities Climate Challenge, an initiative designed to help 25 of the largest U.S. cities slash emissions from transportation and building energy in two years.

Portland was the first U.S. city to adopt a carbon reduction strategy in 1993. For decades, the city has invested heavily in green infrastructure, expanded public transportation and bikeways, promoted sustainable energy and building practices, and passed bold policies requiring responsible consumption. Despite seeing overall carbon emissions drop 19% from 1990 levels, however, Portland’s success has plateaued, a trend which must reverse if the city is going to meet its ambitious 2030 and 2050 climate targets. It’s not for lack of interest—climate concerns are front of mind for many Portlanders. Political will and investment are there, but we’re simply not moving fast enough. Which begs the question: in American cities like Portland that were built around car and fossil fuel infrastructure, are the changes we need to see just too big?

From Institutional Change to Individual Change

For cities like Portland, pushing past the plateau starts with breaking down the different levels at which we need to catalyse change. The climate fight must be waged on many simultaneous fronts. Government agencies must pass laws and change systems that curb overconsumption and pollution. Businesses must adopt greener standards and address supply chain impacts. Community groups must mobilize advocacy, innovation, and collective action. And—crucially—individuals must make sustainable choices in their own lives.

Too often, the more powerful players—the government agencies, major institutions, and business groups—have shirked responsibility and placed the burden squarely on individual actors. On the other hand, the enormity of the challenge can make even motivated individuals feel defeated: if the problems are so vast, do my own daily behaviours really matter?

Each piece of the puzzle is needed to realize the change we need to see as quickly as we need to see it. If governments, institutions, and businesses change their policies and practices, that can make it easier for their constituents or customers to make greener choices. And in turn, if individuals start demanding more sustainable options, that pressure can cause bigger, systemic change.

Rather than wasting energy (and precious time) pointing fingers, cities must adopt a multifaceted approach—and that’s where planners come in.

Planning for the Way People Think

Climate planners can help connect the dots between the actions happening at all these levels to facilitate sustained, meaningful behaviour change.

Much of our traditional planning ethos is rooted in economic rationality. If we make an option more attractive—either by making it better, safer, easier, cheaper, or even just by providing it, period—rational economic theory supposes people will choose those options. This “build it and they will come” hypothesis assumes everyone is constantly running cost-benefit analysis equations in their head as they navigate their daily lives. That’s partly true, particularly in the reverse (people are very unlikely to voluntarily choose to do something if it’s not safe, easy or comfortable). But according to behavioural science, this misses a huge piece of how humans tick.

According to research by Nobel prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman, people only make about 2% of their daily decisions through slow thinking, or the part of our brain we engage when we weigh up the facts and decide what choice makes the most rational sense. The other 98%? Those decisions we make with the fast thinking part of our brain where we form patterns and habits so we don’t have to always think about the nuances. Given the thousands of choices we make every day (“What should I wear today?” “How will I get to work?” “What should I eat for lunch?”), our brains look for shortcuts to avoid a constant state of analysis paralysis.

Bringing it back to planning and climate change, we’ve traditionally tried to encourage sustainable individual behaviour by a) convincing people why they should make those choices, and b) making those choices more attractive. But behavioural science teaches us that telling someone why and how something is good for them is often not enough to change behaviour, particularly if that behaviour is one driven by the fast thinking part of your brain. The best intentions are no match for the power of routine.

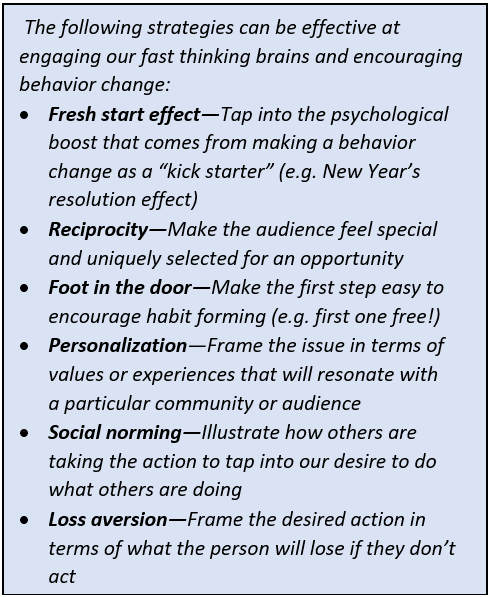

Intervening in these automatic, pattern-based routines requires more sophisticated “nudging” to help people form new habits. If we want to encourage people to change their behaviours, we must consider the phenomena that make us hard-wired to stick with our modus operandi, including things like:

- Status quo bias:Even if changing will result in better outcomes for the individual, we tend to think what we’re doing now is fine enough. Change is uncomfortable, and we prefer to avoid it.

- Optimism bias:When thinking about our habits—e.g., our daily commute—we tend to think about conditions on the “best day,” even if the usual reality is worse.

- Friction:People tend to avoid complexity and multiple steps in their daily routines. Changing behaviour can, at least at first, increase complexity.

Behavioural Science in Practice: Portland’s Experience

In Portland, the Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) is turning to behavioural science as one part of its climate strategy. While overall carbon emissions are down, transportation emissions in Portland have increased 6% over 1990 levels, despite significant investments in green transportation infrastructure. This is partly due to the large number of people moving to the region. More people bring more car trips, the greatest local source of transportation greenhouse gas pollution. Getting Portlanders to choose to walk, roll, bike, ride public transit, or carpool is key to reversing this trend.

In Portland, the Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) is turning to behavioural science as one part of its climate strategy. While overall carbon emissions are down, transportation emissions in Portland have increased 6% over 1990 levels, despite significant investments in green transportation infrastructure. This is partly due to the large number of people moving to the region. More people bring more car trips, the greatest local source of transportation greenhouse gas pollution. Getting Portlanders to choose to walk, roll, bike, ride public transit, or carpool is key to reversing this trend.

Transportation choices often fall into the fast thinking category of decision making. Knowing this, PBOT has developed several programs designed to intentionally interrupt that fast thinking by reaching people at key moments where they may be most inclined to change their behaviour, for example:

When changing address – PBOT’s SmartTrips for New Movers program mails households maps and resources about biking, walking, and transit any time they change address in Portland. The idea is to expose people to behavioural nudges during the “fresh start” window of a home move, before you’re created new routines. PBOT estimates SmartTrips has reduced driving trips among participants by about 8%.

When renewing a parking permit – In neighbourhoods where parking permits are required, PBOT offers a “Transportation Wallet,” which is a discounted collection of passes and credits for use on transit, streetcar, bike share, and e-scooter rentals. Qualified residents and employees can either purchase the Wallet for $99 or get it for free if they give up their parking permit. The Wallet takes the hassle out of accessing these different mobility options individually by putting all of the options right in someone’s pocket. PBOT estimates Transportation Wallet users drive alone to work at about half the rates of non-Wallet users, and nearly 98% of people who purchased them would buy the Wallet again.

When new infrastructure is introduced in a neighbourhood – After PBOT completes a biking, walking, or transit infrastructure project in a community, the work doesn’t stop. Instead, the Bureau takes steps to “activate” the infrastructure—meaning they apply behavioural science-informed strategies to catalyse behaviour change.

For example, PBOT recently completed two new “Greenways”—calm streets designed to prioritize walking and biking—in the diverse, largely car-dependent neighbourhood of East Portland. Rather than just announcing the project’s completion, PBOT is about to launch the GoByGreenways campaign, an interactive game designed to get East Portlanders out on the Greenways with their families so they can experience how accessible, safe, and convenient they are for daily travel. The game is set up as a scavenger hunt: participants search for “zebra” placards hiding along the Greenways (including at local businesses opening after Covid-19 closures) and text unique codes to win prizes. By using personalized mailers, partnerships with local community organizations and businesses, and messaging that responds to the unique context of East Portland, the game feels personalized, making people less likely to ignore it. The game will also use text messaging and social media to encourage East Portlanders to keep playing the game in order to win more prizes and be part of the neighbourhood “movement,” both of which will help make using Greenways a repeated, patterned behaviour.

One Size Does Not Fit All

Tapping into behavioural science is a powerful tool planners can use to spark individual behaviour change and support climate action goals. But just as it is problematic to think people make decisions in the same way all the time, we must not assume everyone can make the choices we might want them to make.

In Portland and many other communities around the globe, that means recognizing Black, Indigenous and people of colour are more likely to experience threat and fear of discrimination and violence in our public rights-of-way. Overcoming this necessitates much more than a behavioural science approach, but rather a broader commitment to anti-racist planning and addressing the root cause of inequities in our cities.

Furthermore, merely having options and the ability to make choices can be a privilege, and one not enjoyed by everyone in our communities. Economic insecurity, gentrification, disabilities, and many other factors can make behaviour change more difficult or even impossible. Planners must be mindful of who they are asking to make changes and how that could further benefit or burden different groups.

Applying behavioural science, therefore, should be viewed as one tool in the toolbox. Tackling monumental challenges like the climate crisis will require the entire toolbox, and more.