In the early 1990s, the city government of Madrid embarked on a journey to modify the previous city plan from 1985. Together with regional and national changes in land regulation, developable land increased by 47% in the city. Over 7,200ha of land were planned and designed at once, an area equivalent to twice the consolidated (please note, not historic) city centre within the M30 ring road. Whilst some of these neighbourhoods have been started in recent years, the first wave was developed in the 2,000s and consisted of six areas.

These neighbourhoods are called PAUs, after the regulatory mechanism that unlocks them for development. They involve unprecedented levels of land development and growth. Given their scale and homogeneity in the way they are designed, they represent a new model of city that was being proposed by the regional government of Madrid through the 1997 City Plan. Why Spanish cities, and especially Madrid, were developing in this particular way?

Given their design characteristics, they were subject to widespread academic and professional criticism. At the time they were starting to be built I was at the School of Architecture of Madrid, where there was a clear line of thought that these developments were against the contemporary urban and architectural conventions given some of their characteristics like oversized public space and social infrastructure, poor public transport links and car-dominant developments, as well as poor architectural diversity.

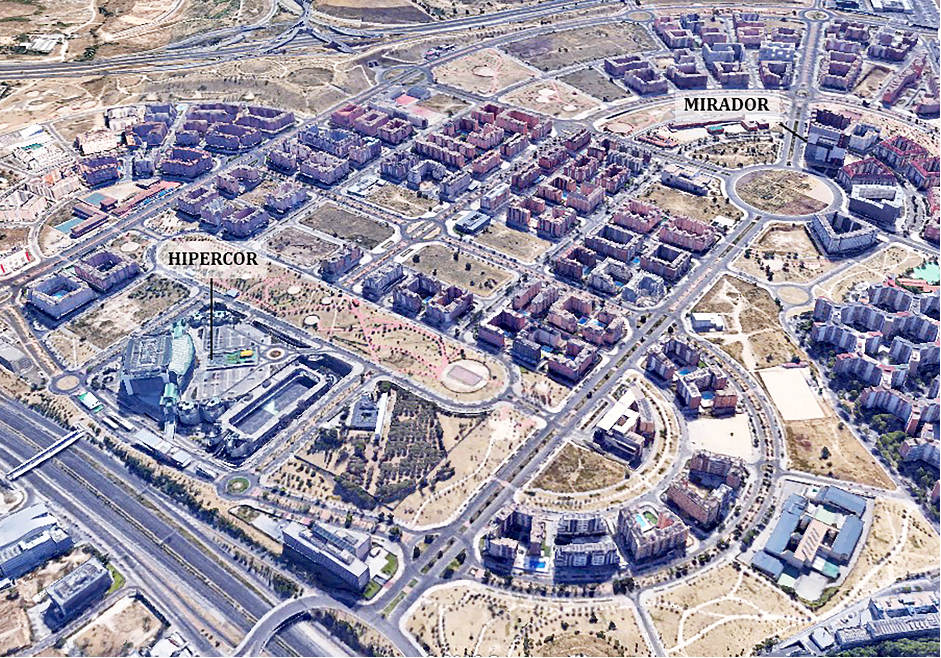

Our research focused on Sanchinarro, arguably one of the most representative of these areas. The furthest developed of them, with a 98% level of completion as of May 2015 (figure 1), and the largest of the four adjacent neighbourhoods the north of the city centre. The aim of the research was to find out how these neighbourhoods, clear target of academic and professional criticism, worked 10 years after being first inhabited by bringing together design criteria and the experience of residents in order to draw conclusions about the extent to which the PAU design matches the population’s needs and demands. We applied a theoretical framework from Kevin Lynch’s seminal work ‘The Good City Form’ (1981) through over 20 semi-structured interviews to residents and following thematic analysis.

Figure 1 – Sanchinarro PAU at 98% of completion

An initial background research and literature review confirmed, if not exceeded, most of the criticisms poured over these neighbourhoods. Whilst the compact city debate was not the focus of this paper, we found evidence that planning authorities were against the contemporary conception of urban growth. The European Commission was already promoting the compact city when PAUs were being planned. Our interview to the architect behind the City Plan from 1997 demonstrated an intentional direction towards road infrastructure, more characteristic of mid-Century comprehensive planning, and low residential densities. However, these characteristics seemed to have a positive impact on residents and were mentioned as desired qualities and reasons that made them move there.

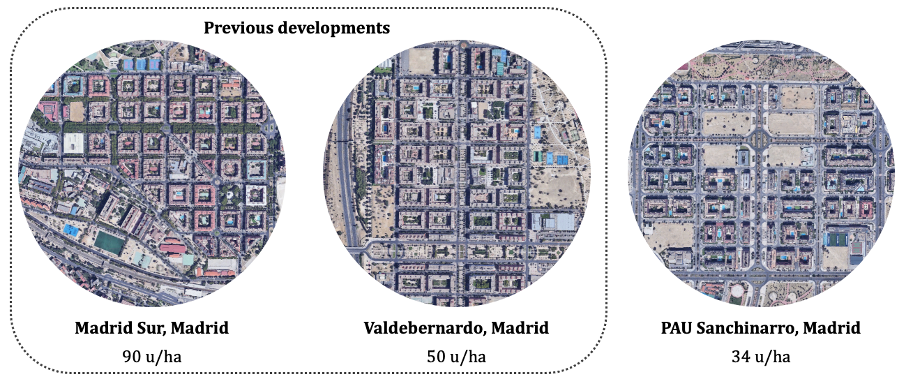

Particularly, Sanchinarro had a density of just below 34 dwellings per hectare, substantially lower than urban extensions from the previous city plan (PG85). Madrid Sur and Valdebernardo had densities of 90 and 50 u/ha respectively. Understandably, green area ratio is higher in Sanchinarro with a 31% of the total land being designated as green space. The block size is also larger, what allowed the designers to set the blocks back from the street and build fences to separate the public and private space, something you would intend to control by the use of the perimeter block, the typology used by default throughout all these neighbourhoods.

One of the findings stood out from the rest – 90% interviewees stated that Sanchinarro was a pleasant place to live even though it was not explicitly part of the questionnaire. Elements like the width of the streets and sidewalks, the distance between buildings and the openness in general are really appreciated by residents.

Other key findings showed a lack of identity in terms of the built environment, but strong social identity due to links to the community through the inner courtyards part of the perimeter block typology and the community centre. In relation to the public open space, there was a lack of perceived designated green open space despite the large proportion of it in the development. This is clear result of the poor maintenance and design qualities of parks and green areas given the political and social context in which they were conceived. PAUs were planned and designed in times of economic optimism and a real estate boom in Spain. That led to an oversupply of social infrastructure and open space that the Council was not able to maintain and build, which resulted in fragmented and poorly maintained urban areas.

However, residents were not keen to trade-off spaciousness for other aspects relative to the compact city such us more local retail, better maintained green areas, weather protection and better public transport, what challenges the compact city theory and convention. Also, the cause of dissatisfaction normally lied with the failure to deliver all the public services planned rather than design issues, although both are intrinsically linked. Their expectations and lifestyle may not always be met, and it is not necessarily always achievable, but at least in this case there seems to be a big gap between professionals of city planning and residents’ experience. That shows the need for a further alignment between everyday life experience, design codes and public resources to achieve sustainable development.

Re-watch on Youtube our webinar Density: Design and Perception