If you’ve ever attended a public meeting in an urban area anywhere in the United States, you are probably familiar with this scene. Municipal planning staff, potentially joined by a handful of consultants, seated behind a long table poised to give a presentation to a room full of residents passionate about their neighborhood’s need for more stop signs, cross-walk repainting, additional garbage cans, and a bus-only lane down Main street. While there is much worth critiquing in this scene (i.e. the layout of the room, the town hall meeting format itself) let’s focus for a moment on the one element that seems ever-present no matter where in the country this scene takes place: the often gross imbalance between the proportion of Black women in the crowd and those on the decision-making side of the table.

Despite being one of the most civically active demographic groups, representing a disproportionately high proportion of the nation’s urban population (17% compared to their 7% share of the total national population), and being heralded as the ‘pillars’ of their communities, in 2019 black women comprised just 3% of employees in the field of urban planning.

Given for how long, and just how far and wide published works have been calling to attention the major shortcomings in race and gender inclusivity that plague the field, this likely comes to you as no surprise. We see it across headlines shared by major planning collectives – “Urban Planning Can’t Happen without Black People in the Room – Yet it Does” (Congress for New Urbanism, 2017); in reports released by international organizations – “Can Urban Planning Take Into Account Women and Minorities?” (World Bank, 2020); and even in mainstream media – “Urban Planning has a Sexism Problem” (Next City, 2017), “Why Women Matter in Urbanism and City Planning” (Forbes, 2018). However, few of these platforms focus in on the particularly short end of the stick that Black women in, or kept out of, the field receive. This piece aims to shed light and invite conversation on exactly that.

What We’re Seeing: Learning from Trendlines

Despite the seemingly endless list of appropriately marring headlines, the field of urban planning is enjoying a sort of thriving renaissance period at the moment. More and more universities are starting new planning programs and existing programs are expanding their course offerings, increasing their staff capacity, and taking on more and more students each year. The field’s Job Outlook – a metric used by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics representing the projected percent change in employment within the field from 2019 to 2029 based on recent trends in the number of positions available nation-wide – is 11%. This is well above the Job Outlook averaged across all other occupations, which weighs in at just 4%. With no shortage of jobs in site, it’s a great time to be a planner.

Is this growing field successfully shaking its well documented and long-discussed issues of sexism and lacking Black representation within its profession workforce. To get a sense of how the professional body of this booming field is, or is not, making progress let’s examine the numbers (which I acknowledge never tell the whole story, but are a good place to start).

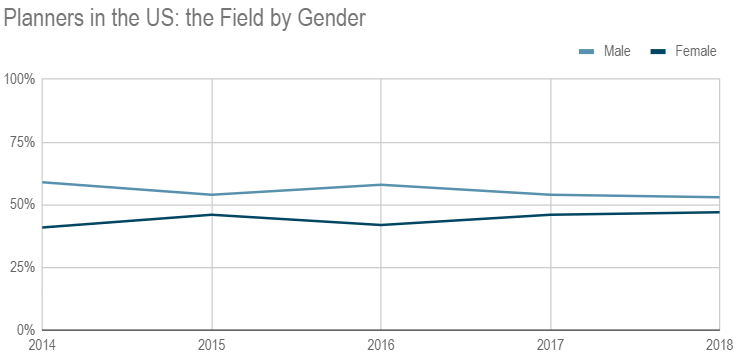

Data Source: American Community Survey PUMS 1-Year Estimates

Within the past decade, women have indeed been making gains with respect to their physical presence in the field. Representing just 41% of US planners in 2014, women made up 47% of the field in 2018, and the most recent census data reveals that proportion continues to climb, currently sitting at 49%.

Without question, this is progress. However, digging a layer deeper reveals a set of continual imbalances. This significant rise in women planners is not evenly being enjoyed by all subsects of planning. These gains are heavily screwed in favor of the branches of housing, environment, and policy. Unfortunately, engineering, analytics, transportation, and design remain heavily male dominant and are not seeing the positive trends in increased gender diversity and inclusion that the aforementioned groups are.

Nonetheless, planning is growing increasingly female. Perhaps not as quickly as many of us would like, but forward motion is nothing to scoff at. Are we witnessing the same forward motion with respect to Blackness within the field? Are my days of not seeing a mirrored face across the table at planning meetings soon to reach their end? Don’t hold your breath.

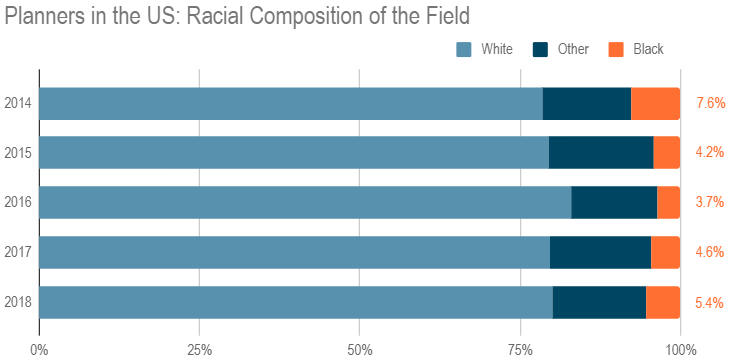

Data Source: American Community Survey PUMS 1-Year Estimates

The percentage of US planners who identify as Black has fluctuated over the last decade. The largest of these fluctuations was a drop of 3.9% between 2014 and 2016. Since then, Black employee presence within the field has increased – albeit at the measly rate of less than 1% a year. Even so, the proportion of planners who identify as Black has yet to recovered to its pre-2015 level.

Unsurprisingly, the readily available data fails to speak directly to trends along the lines of intersectionality between being both Black and a woman. As a result, to allow for comparison, let’s say that 100% of the change in Black employee presence in the field were attributed to women. That would mean that between 2016 and 2018 women on the whole saw their share of position holders raise by 5% while Black women saw their share raise by just 1.7% – and that is at an absolute and unrealistic maximum! Needless to say, this stat fails to ignite a sense of hope and revolution.

Now the optimists among you might be thinking, “2018 was a little while ago, I bet we are heading more definitively in the right direction now. With awareness of the field’s importance growing and more educational opportunities than ever, there must be an increasing share of Black women in the planning pipeline currently in school working toward their degrees. It will get better soon, surely.” Oh how I wish the trendlines shared your positivity.

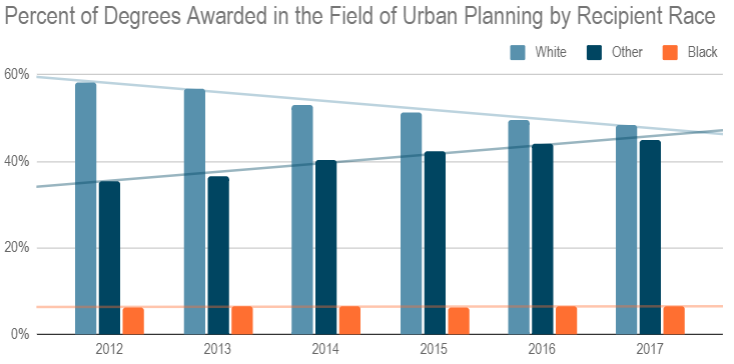

Data Source: Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) – Completions

Indeed the data collected on the racial identities of planning degree recipients in the US paints a promising picture with respect to some facets of diversified representation. In recent years, a decreasing share of recipients have identified as White. However, while the field ushers in a growing share of racial minorities, the share of degree recipients who identify as Black has remained painfully stagnant. In the absence of this data cross-tabulated by both race and gender, it is fair to follow the logic that the only way for the share of Black women to be growing in this scenario would be for the share of Black men to be shrinking. Since that is certainly not the goal, the educational pipeline data ultimately depicts a bleak picture with respect to our current focus.

Why Does this Matter

So we have established that Black women are disproportionately poorly represented among planning professionals in the US. Now let’s chat about what implications this has for planning work at large.

There are many concrete examples of how planning in the absence of women has manifested itself as inequitable design decisions in our built environments. Parks with inadequate lighting creating unsafe feeling spaces, a lack of public restrooms, sidewalks too thin or obstructed to push a stroller down with ease are a few regularly sited examples. In facts, we’ve heard these particular design tragedies made reference to so often that they’re starting to feel rather patronizing, as if the only way women interact with cities is by having highly active bladders and tending to children… a topic for another time.

Less often discussed, but just as true and just as problematic, is how the lack of women in planning has shaped many of our public transit systems. The standard 9am to 5pm workday is associated with a commuting schedule adhered to by positions dominated by men. Women make a larger portion of their trips outside of the typical ‘peak periods’ that transit planners design service around. Additionally, women make not only more total trips per day than men, but also more local trips. Meaning that a system focused on taking workers from their homes to a nuclear job center and back, serves the travel needs of men more comprehensively than those of women.

The role that planning has played in contributing to the disenfranchisement of Black America has a similarly rich literature backing it up. Through exclusionary, racist, and predatory real-estate practices, planning has barred Black communities from the strongest wealth accumulation machine we have: private property ownership. By dividing Black neighborhoods with colossal highway projects, and blatantly racist allocation of green-space funding, planners have contributed to disproportionately high asthma and obesity rates among Black children. Planner-approved school district gerrymandering has played a huge role in the worsening educational attainment gap across racial lines that many US urban areas suffer from today. While we will never know how having more Black planners on these decision-making teams might have altered these realities, it is fair to assume that their increased presence would likely have rendered planning not quite so effective and widespread a tool of long-lasting oppression.

Hopefully it is clear why having both more women and more Black people working as planners is important for how our cities function and take form. But you may be feeling that the question of why more Black women in particular are called for, remains. The answer, as I see it, boils down to a single, powerful concept. Trust.

Let’s say planning gets its act together across the board, and fully commits to a whole host of sustainable, equitable, resilient, (and most importantly) transparent practices and ideals. Without trust between planning professionals and the public, it is all for naught. In my years as a planner, I have found that despite good intentions, in the absence of trust, the system will continue to perpetuate an inequitable distribution of resources as Black residents will either, and logically so, participate with a defensive strategy – ‘Sure, a pocket park and a new bike lane sound like a good idea, but I don’t trust you to accompany it with protective housing policies that ensure I won’t be displaced by young, wealthy, white folk who love a good bike lane and a patch of grass, so I’m voting against it’, or not at all – ‘No matter what we say we want in our neighborhood, you’re going go ahead and do whatever you like, so I might as well not waste my time showing up’.

Why is the bridge building of trust more important with Black women than anyone else? Think back to our opening premise: Black women comprise a uniquely strongest voting block across the nation’s urban centers, and are well established as the ‘pillars’ of their communities. This combination of say-so and respect is not something to ignore. Close collaboration between the planning field and Black women, given the civic power that they hold, may be the best shot at thwarting what many have deemed the largest crisis facing Black America today: gentrification.

Gentrification, though it can feel like an unstopped wildfire, takes root at a hyper-localized level – one street or even one building complex at a time, then a trickle over from one neighborhood to an adjacent neighborhood, and so on. Planning’s most effective tools are also often hyper-localized – zoning codes at the block-by-block scale, Mainstreet merchant assistance grants, the addition of real-time arrival signs at a transit station, the establishment of community gardens on an individual City-owned parcel, to name just a few. It is at this same hyper-localize scale where their established civic engagement records, community presence, and regular occupation of leadership roles may afford Black women their most powerful platform from which to shaping the trajectory of America’s cities.

But for planning to effectively flex this anti-gentrification muscle, Black women need to feel that their voices are not only being heard, but are being championed by trustworthy agents within the system. In today’s America, one of growing division, it is hard for many to believe that that champion can come from anyone who isn’t, at the very least, both Black and female-presenting themselves. For starters, it is human-nature for us all to find those who resemble ourselves, more trustworthy than those that don’t. Similar skin color, assumed shared gender, similar accents, and even similar height are all lines across which we unconsciously establish connections. Beyond that, US society is such that the assumption of shared experiences, shared prejudices, shared fears, and even shared goals by members of both the same minority race and gender is indeed a fair one. This only further strengthens the argument that to truly surpass centuries of earned mistrust and tap into the latent power that Black women could wield in a system that wasn’t designed for them, but may yet serve to protect their claim to their cities, their homes, and their communities is the presence of planning professionals that better reflect these women’s lived experiences and values. Plain and simple, representation matters.

Positive Ways Forward

Those of us in the field of planning wholly unsatisfied with the comparative dearth of Black women that we can call colleagues have a responsibility to be active agents of progress; our next steps must be boldly forward. Some groups are already making positive moves toward this shared aim. Mimicking these practices in our own organizations may be a solid starting point.

The University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design – home to a Top 10 planning program – offers several diversity and Inclusion scholarships at both the Masters and Doctoral levels of planning study. These awards range from $12,000 to full tuition and cover a student’s entire degree tenure. They are specifically for students who reflect “underrepresented groups within academia” or whose background experiences “offer varying perspectives on living and learning in a multicultural world”. While you might be thinking that this is nothing new, and that in today’s world many programs offer such opportunities, UPenn has gone a step further than most in making these financial offers easily accessible to students who would qualify. The applications for these funds are limited to just 500 characters and are embedded directly into the program’s application. By making these funds substantial in size, easy to find, and quick to apply, UPenn has conquered key hurdled that prevent students from taking advantage of available, inclusion-focused financial support.

In their recruitment efforts, the Boston Transportation Department went away from a one-at-a-time, or as-needed, staffing practice and hired 11 new mobility planners all at once. One might call this batch-hiring. Not only did the City’s commitment to increasing diverse representation on staff show – 55% of new hires were women (compared to 38% of existing staff), 27% identified as people of color (13% among existing staff), and with this round of hiring their planning team went from 0% Black women to 6% – but by onboarding this group all at once, they reduced the air of tokenism that often accompanies the early steps toward inclusive representation within the workplace.

Shouldering the burden of being the black person, the queer person, the women, or the differently abled person in the room is taxing. Note that this list is only the tip of the iceberg, and doesn’t even begin to examine the compounded burden present in the world of intersectionality among these pieces of identity… yet another topic for many another piece. Studies show that having structures in place that allow for that burden to be collectively shared is vital not only for minority staff joy and satisfaction, but also for their retention. It’s been two years since Boston’s batch-hiring, and having retained 94% of their planning staff while significantly improving their on-staff minority representation, it is fair to say that there may be some merit to Boston’s batch-hiring method.

The rigidity of required qualifications for employment opportunities currently functions as a major barrier to entry for many Black women in or seeking to enter the field of planning. I have heard it from HR personnel in both the public and private sectors enough times to make me mad just typing it: ‘… we want to hire a person of color, but none who have applied so far meet the qual. specs.’ Well when the ‘specs’ cater to the existing, white-serving knowledge-acquiring system in place, that should come as no surprise. According the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the typical level of education that most workers need to gain entry into this field today is a Master’s Degree. This is likely why related fields, such as organizing and advocacy, which place a more appropriate weight on a doing value-system versus a training value-system are experiencing a faster rise in their share of both women and Black professionals than planning is.

The planning field needs to start acknowledging that Black women have been doing planning work without academia accredited planning training since the concept of planning was birthed. We need to credit their experience, value it, and find a way to appropriately and competitively compare their wealth of knowledge with more traditional – read white-serving – education backgrounds.

It is my hope that with creative, barrier crumbling practices like these we may yet in my lifetime reach a place in which today’s headlines of “Urban Planning as a tool of White Supremacy” (The Conversation, 2020) are replaced by ones the likes of “Urban Planning: a field Teeming with Black Women”.

I graduated with a MA in planning back in 2018 from a supposedly public minded school-but really it was just the same old patriarchy as usual. I had been working in education for about 2 decades and wanted a change. It was my third degree and I naively thought that it would open doors for me in the field. Ha! Turns out formal academic credentials and internships are basically meaningless when you are a black woman so I went slinking back to the velvet ghetto along with many of the other women of color in my cohort. I could have saved the 20K and two years of study and just read books on my own and not gotten a job. Lesson learned. I thought ed. was racist and exclusionary but planning takes the cake and that’s why our cities are they way they are.