This post was originally written as part of PB101: Foundations of Psychological Science, a compulsory course on the BSc Psychological and Behavioural Science undergraduate programme at LSE. It has been published with the permission of the author.

Autistic girls:

- Have friends

- Have ‘normal’ interests

- May look anxious

- Have mental health issues

They’re hiding in plain sight.

‘Autism’ might evoke the character Sheldon Cooper or a boy crying and punching himself. You certainly wouldn’t imagine a daydream-y, boyband-obsessed girl who does poorly in maths. But as it turns out, they are exactly the girls who spend most of their lives being misunderstood, questioning what is wrong with them, only to discover as adults that they are autistic (Leedham et al., 2020). So, how does Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) go unnoticed for so many years?

Autistic girls “make wonderful spies” (Attwood, 2015)

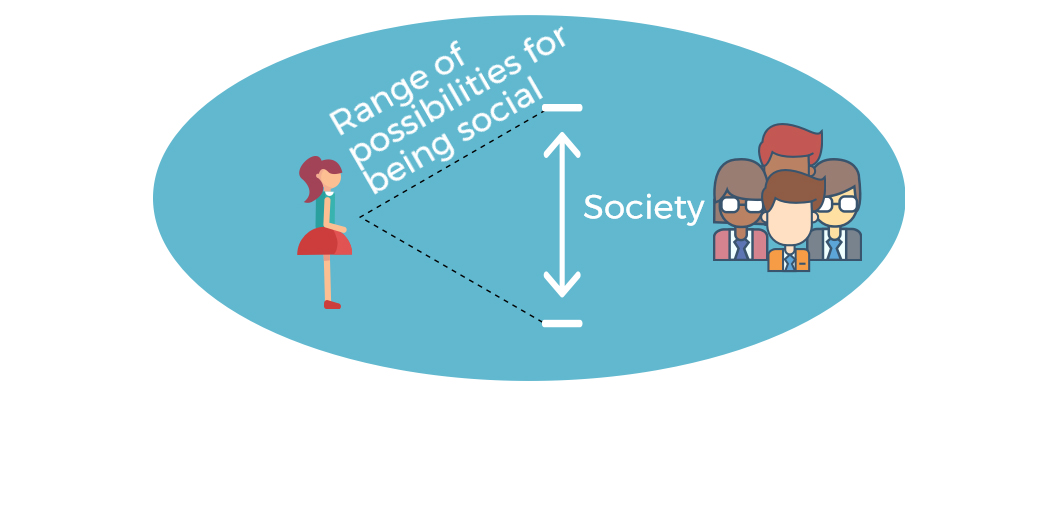

Autism may express itself entirely differently in boys and in girls, giving rise to a ‘female autistic phenotype’. A phenotype encompasses an individual’s visible characteristics resulting from their genotype and their environment interacting.

Females at the lower end of the spectrum may be exceptionally skilled at mimicking their peers. Part of the reason for this is that girls – autistic or not – are much more inclined to socialise. If they are unsuccessful, they’ll feel lonely and rejected. They also have higher executive functioning skills than boys, making masking a much easier task to undertake. So they analyse and mimic, until eventually, they ‘look normal’ (Tubío-Fungueiriño et al., 2021). So, why would you think they’re autistic?

“When I actually got tested I was on autopilot and it meant that I got misdiagnosed” – Autistic woman (Milner et al., 2019, p. 2396).

She’s not crazy, she’s autistic

Being autistic and, additionally, masking your true self, comes with a host of mental health issues. Most common are anxiety, depression, OCD (Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder), ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) and Anorexia Nervosa (Tubío-Fungueiriño et al., 2021; Margari et al., 2019), and autistic girls suffer from more co-morbid disorders than autistic boys (Rødgaard et al., 2021). So, if an ‘average’ girl comes to your office presenting symptoms of the above-mentioned disorders, aren’t you more likely to think ‘she has OCD’ than to ask yourself ‘What if she’s autistic?’?

She loves Harry Potter, ask her anything!

Intense and persistent ‘special’ interests are a core feature of ASD which can be stereotypically portrayed as obsessions with, for example, train wheels, calendar dates and numbers. While this is true for many autistic boys, girls may love animals, The Spice Girls, and books (Tubío-Fungueiriño et al., 2021; Lai et al., 2011).

‘Isn’t that what most little girls like?’ It is! But dig a little deeper, and they know every chapter of every Harry Potter book, every character and actor’s biography, and the entire life story of J.K. Rowling. You may not know this, however, so why would her interests seem ‘unusual’ to you (Suckle, 2021; Attwood, 2015)?

She doesn’t punch and scream, she picks her nails…

Another core feature of ASD is sensory processing issues, making bright lights and loud noises feel like an attack. Often, sensory stimulation accumulates and creates ‘sensory overload’ leading to meltdowns and shutdowns.

“So, shutdown I associate with myself just going like really quiet, I don’t want to interact, um, a meltdown will be like really tearful, upset, angry, distressed, um it’s kind of cathartic to me sometimes” (Milner et al., 2019, p. 2397).

One way autistic individuals cope with this is self-stimulatory, ‘stimming’ behaviour. A classic example is a little boy flapping his hands and punching his head. But girls are on the ‘quieter side,’ anxiously picking their nails, biting the insides of their cheeks or doing other small, repetitive movements (Charlton et al., 2021; Suckle 2021). Doesn’t this look just like anxiety?

Do the doctors really see her? Do her teachers?

Gatekeepers to autism assessment and diagnosis are parents, teachers, doctors and other specialists. But are they biased? Yes. Alana Whitlock and her colleagues found that schoolteachers are more sensitive to the male than to the female phenotype. They are not likely to refer a girl presenting the female phenotype for further help, and for two children presenting the same traits, they are more likely to refer a boy. Part of the cause is: I know autism is more prevalent in boys, so I expect more autistic boys. Therefore, I won’t focus on girls possibly being autistic (Whitlock et al., 2020). Once girls get older, they receive every diagnosis under the sun except for autism. Even if they suspect it, they feel like they’re told ‘You’re not autistic!’ (Bargiela et al., 2016).

“I should have just burnt more cars” – Autistic woman (Bargiela et al., 2016, p. 3285).

How can you understand her if you exclude her?

We want to understand the female phenotype, and why girls go undiagnosed. But how can we study undiagnosed autistic girls if we aren’t sure they’re autistic? We can study girls who are diagnosed, but that excludes the girls we’re trying to study. Furthermore, current diagnostic criteria are based on male presentation, so girls who are diagnosed are not the most accurate representation of the female phenotype (Bargiela et al., 2016). Studying girls who score high on tests such as the Autism Quotient (AQ) (Lai et al., 2011) or speaking with late-diagnosed women through questionnaires and interviews has shed some light (Bargiela et al., 2016). But how can we better diagnose girls if we’re having trouble understanding their autistic experience?

“I think it would be nice for people to realise that autism can affect girls” – Autistic woman (Milner et al., 2019, p. 2399).

She’s tired of paddling…

Sarah Hendrickx and psychologist Tony Attwood, linked below, paint vivid portraits of autistic girls both from a clinical and a personal perspective. Autistic girls are invisible genii who often feel lost, never really knowing why they felt so ‘alien’ their whole lives. The very nature of their autistic selves makes them unseen, while parents, teachers and doctors seem equally blind to them. As one woman puts it, “It’s kind of like a duck on water you know it’s calm on the surface but sort of paddling really hard underneath.” (Milner et al., 2019, p. 2396).

Further information

Aspergers in Girls (Asperger Syndrome). – Tony Attwood.

Girls and Women and Autism: What’s the difference? – Sarah Hendrickx.

Notes

- This post expresses the views of the author and not the Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science nor LSE.

- This post was originally written as part of PB101: Foundations of Psychological Science, a compulsory course on the BSc Psychological and Behavioural Science undergraduate programme. The post has been published with the author’s permission.

- Small duck swimming in lake water by Skylar Ewing, 2020, Pexels.

- Image of a woman with a horse by Dorota Kudyba, 2018, Pixabay.

There’s a lot of information I feel the author delivered in a very engaging way. Thoroughly enjoyable!

The Blog was quite commendable! It was really informative and the author presented it in a rather engaging manner!