In a recent study, Ivica Petrikova has found that religious believers are more likely to support an ‘internationalist’ foreign policy. Believers are likely to be more militant and also tend to be more cooperative in their foreign policy outlook. This is evidence of religion’s twin tendency to foster both hostility to others and an altruistic universalism.

Recent events including the rise (and fall) of Islamic State and Boko Haram and religiously motivated terrorist attacks across Europe suggest that religion still plays an important role in international affairs. International survey results validate this: by 2050, the global percentage of religious people is expected to grow from the current 84% to 87%. Therefore it is likely that religion will retain important influence on international relations for the foreseeable future. But it is less clear what this influence will be. New evidence I have published as a result of cross-country research shows that religion makes people more militant in their foreign-policy views while its effect on cooperative foreign-policy views is more nuanced.

What is religion?

Religion has been commonly defined as people’s personal beliefs about the supernatural as well as the institutionalised systems of such beliefs. It is also seen as an integral part of one’s identity and a source of world views and values that serve as a guide to right living. However, despite the complex, multi-faceted nature of religion, many studies have measured it merely through questions about the frequency of attendance of religious services. To avoid this mistake, my new study measures religion through people’s personal views of themselves as religious or not religious, their self-declared religious faith (None, Christian, Muslim or Other), and their frequency of religious practice. The study also considers whether people are in the religious majority or minority in the country where they live and whether the country is relatively rich or poor.

How are people’s foreign-policy views measured?

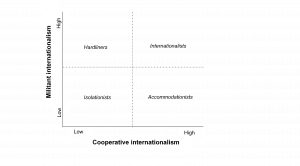

Foreign-policy views are traditionally measured along two different axes – cooperative and militant internationalism. Cooperative, or altruistic, internationalism is an attitude that emphasises the importance of international cooperation, international institutions, and the welfare of people globally. Militant, or hegemonic, internationalism sees other countries as a possible danger to one’s own and considers occasional use of force in international affairs an unavoidable necessity. The two opinion axes are orthogonal and people’s views on them thus give rise to a four-fold classification into ‘hardliners’, ‘internationalists’, ‘accommodationists’, and ‘isolationists’.

My study measures cooperative internationalism through people’s support for providing foreign aid to poorer countries and for the United Nations, and militant internationalism through their support for the use of force in international affairs and for the army directing foreign policy.

Effects of religion on foreign-policy views

Because most religious faiths emphasise the importance of altruistic values including caring for others and reciprocity, the expectation was that religion would strengthen believers’ feelings of cooperative internationalism. Simultaneously, since most major religious texts contain violent accounts and support the use of violence against followers of other faiths, religion was expected to also increase believers’ support for militant internationalism. The study’s findings primarily support the second expectation.

The study examined the effects of religion on people’s foreign-policy views through a quantitative analysis of data from the World Values Survey, gathered in 89 countries between 1994 and 2014. Regardless of how religion was measured, it was always found to increase believers’ support for militant internationalism.

However, different measures of religion have very different effects on people’s attitude to cooperative internationalism. Whilst most religious measures used increase people’s feelings of cooperative internationalism, this is less often true about people classifying themselves as Christian, practicing religion only infrequently, and/or living in richer countries. In contrast, the Muslim faith, frequent religious practice, and belonging to a religious minority mostly strengthen believers’ support for cooperative internationalism.

Policy implications

People’s foreign-policy views do not directly translate into countries’ actual foreign policy. But they may influence policy, particularly in democracies as well as in those autocracies that perceive foreign policy as an issue of relatively low importance. Furthermore, people’s views on how their countries should relate to others inevitably shape the construction and understanding of national interests over time and thus ultimately affect their countries’ behaviour in the international arena.

The finding that religion in all its guises animates militant foreign-policy views among believers, against the backdrop of increasing global religiosity, is thus not encouraging. At the same time, the study’s results showed that how precisely religion affects cooperative internationalism varies in line with different aspects of religion (belief, belonging, and behaviour) and its social standing, demonstrating that, like culture, religion and its effects are fluid and malleable. Accordingly, if there is an interest among policy makers to strengthen religion’s cooperative effects and weaken its militant effects on people’s foreign-policy views, it could be supported by, for example, modifying which moral values are elevated in religious sermons and how different religious faiths are depicted in the media.

About the author

Ivica Petrikova is a Lecturer in International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London. She is also a co-director of the Centre for Politics in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East (AAME). Her main research interests include the relationship between religion and politics, effectiveness of development aid and public social programmes, and food security.

Ivica Petrikova is a Lecturer in International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London. She is also a co-director of the Centre for Politics in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East (AAME). Her main research interests include the relationship between religion and politics, effectiveness of development aid and public social programmes, and food security.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Dr. Ivica

Loved reading the article however I would be interested in knowing that if you have to give an example of the Cooperative internationalism and militant internationalism, then which country will you name for each category.

Is there any full-length paper that I can read?

Many Thanks!