LSE Sociology research student and footballer Marion Lieutaud and her team-mate Eponine Howarth (Department of Law undergraduate) say we should call time on the sexism which is still a part of the culture in LSE team sports.

2018-2019 has been an incredibly successful season for women playing football and futsal (indoor 5-aside version of football) at the London School of Economics. The first ever LSE female futsal team finished 2nd in the League and reached the Cup Final – only to be defeated in extra time. The women’s football team currently sits 3rd in BUCS with a couple of games in hand. Despite these achievements, women in football as in the world of LSE sports at large are hardly dealt an easy hand.

The LSE men’s rugby club was suspended in 2014 for publishing an outright sexist and homophobic leaflet distributed at the Fresher’s fair. This very week, an open letter was published by the Athletics Union (AU) in the name of “Women of the AU”, calling out the men’s rugby club in particular for horrendously misogynistic chants and for a track-record of sexual abuse and assault. It also puts the AU and the Students Union (SU) on the spot for failing to address the repeated complaints raised by women about the matter in the past year. The problems clearly haven’t gone away, and they are not limited to male rugby players, or to such shocking and unambiguous acts of sexism as those addressed in the open letter. In fact, it is often the case that nothing comes out publicly until the point where it becomes so obvious and so dreadful that we finally feel legitimate (and exasperated) enough to bring it to the public sphere.

This is because more often than not, the undermining of women in sport comes from people who would simultaneously claim to support gender equality in the abstract. The experience of women in football – as in other sports, no doubt – is one that highlights pervasive sexism and insidious discrimination. These subtler but ubiquitous expressions of gender hierarchies in a sexism that doesn’t say its name is what this article chooses to focus on.

Sit like a lady

Up until this academic year, the LSE Athletics Union displayed the photos of all the LSE sports clubs in their office. Invariably, women would have their legs tightly held together and their hands on their lap. Invariably, men would be sitting knees apart and their hands on their knees.

This year, during the official picture for the Futsal Club, the newly mixed context made the gender disciplining unmistakable. ‘Ladies! Heels together, knees together, hands on your lap. Guys! Feet apart, knees apart, hands on knees’. With hasty justifications of height, the women’s team was split and positioned on the edges of the picture, on each side.

Afterwards, we had a chat with the male photographer. ‘Why the gendered instructions?’, we asked. The word “traditions” eventually concluded our conversation. We just didn’t expect that the upholding of traditions included explicit gendered choreographies in 2018, in England, at the LSE. It turns out that here we are not just taught the ‘causes of things’ but also the ‘order of things’: this includes reminders that women should sit small and that men ought to man-spread. Welcome to the LSE’s sport culture.

The lads’ disdain: can women even really play football?

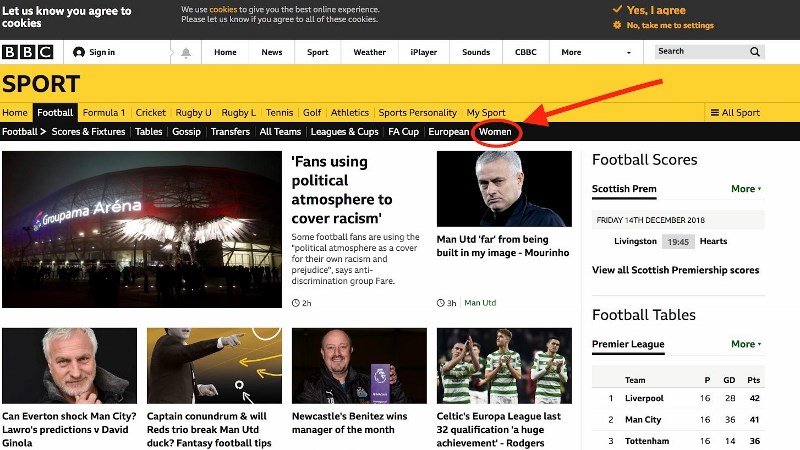

In the realm of LSE football, gender hierarchies are hardly invisible or hidden. The LSE boasts two football clubs known as the Football Club (FC), and the Women’s Football Club (WFC). Why the first one is not called the MFC (Men’s Football Club) is a mystery, or rather a thinly-veiled consensus that football is a man’s sport.

The WFC’s and futsal coaches and referees have always been men. Some – like the current ones – have been brilliant. But some were vastly unqualified and condescending, and of course, the players were aware and resentful of that.

The experience of male disdain towards women who play football is a desperately common one at the LSE. In 2016, the male captain of the LSE Boxing Club, also 2018-2019 SU activities and development officer, told the WFC captain and 1st Team captain that “[he] plays football better than any girl in WFC”. Uncalled for, the assertion was also nothing short of daring, considering that the club included several semi-pros and former semi-pros. Of course, he could not have possibly known the level he was comparing himself to, for he had never seen the women’s team playing or training. His example hardly constitutes an isolated case. How many times have we heard random blokes proudly claim that their casual Sunday soccer skills would suffice to beat the LSE Women’s team. How could we not wonder that they should fail to see the blatant sexism and offensiveness of their comments, and why they felt the need to say them out loud – and to us! And this is not even getting into all the double-edged compliments that taught us to expect that “you play so well” tends to be followed by “… for a woman”.

Of course, the level is, on average, not as high in the women’s football team as it is in the men’s football team: that is largely another consequence of the problem of asymmetrical socialisation to sport, especially acute in male-dominated sports like football. Most men played football at some stage of or throughout their childhood; most women did not. But nobody who pays attention could avoid seeing the seriousness, the dedication and energy that women at the LSE put into their sports, and that this should be met with prejudice and disdain rather than respect is disgraceful.

Refereeing women’s football: benevolent sexism or I don’t know what is

The gender-biases are also apparent on the pitch, in the quality and style of referring. Over the last couple of years, WFC players have been asked “not to be too physically engaged so as to avoid injury” after perfectly safe tackles which involved no collision or sanction. Paternalistic concern for the safeguarding of women’s bodily integrity is combined with the general dismissal of the seriousness of their engagement – both physical and mental – in the sport. While the game is often stopped for no valid reason, cards are virtually never given even when they would be deserved.

Of course, dissatisfaction with referees is in no way specific to women’s football. But there is little doubt that such sloppy and ad hoc refereeing practices would not be tolerated in men’s competitive university football matches. Try to imagine a woman refereeing a competitive men’s match in this way; or picture the LSE’s men’s first team being coached by a woman with disputable competence and qualification. The fact of this inconceivability is telling: football is men’s domain; being a man grants football authority over women – regardless of actual skills, expertise or engagement.

The battle of the pitch

In February 2017, the Women’s First Team Captain raised the issue of the unfair allocation of pitches in a post on Facebook, which became the crystallisation of rampant sexism in LSE football. The Men’s Second Team were given priority over the Women’s First Team for the best quality pitch. Along with statements such as “You know that sometimes you guys use our pitch”, which are plenty, the situation came as the embodiment of a sports culture that assigns sportswomen a secondary role, explicitly assuming that sports facilities are men’s property and that women’s presence and use of said facilities are merely indulged. The women’s captain who attempted to question the pitch allocation was rebuffed and humiliated in the process, which led to the WFC committee’s addressing the AU in a Facebook post.

As is often the case with social media, the comment section under the post is the most telling part. Many men from the LSE’s men’s football and rugby clubs tagged each other under the post, without leaving any further comment, explanation or reaction. Combined with the striking amount of men who rallied to “like” the Men’s captain’s comments and did not react to the post itself or to any of the women’s comments, this came off as a strange display of force. This show of male solidarity, of course, has potent powers of intimidation. It also takes a serious toll on the women who raise the critique. When it comes to publicly questioning privileges, the costs of defiance are very real. Of all the comments on the post – there wasn’t one comment of support from a man.

Vanishing responsibility: if no-one is to blame, is there a problem at all?

Most people agreed that the pitch allocation had been unfair. Yet it remained entirely obscure who should be blamed. The Men’s club captain and second team captain had stated that the Men’s team was not responsible for pitch allocation and asserted that the groundsman was. The groundsman on the day had also shifted the responsibility onto his superior, who was not there. WFC was never able to locate the person responsible for the sports facilities in Berrylands, as various staff members during the following weeks all declared that they were not ‘the person in charge’. The AU like the SU staff stated that they were not responsible for the sports facilities. Needless to mention, the LSE is not responsible for the incident, as the AU is a student body run independently from LSE’s administration.

Of course, elusive responsibility is a well-known strategy to guarantee inertia and preserve the status quo. As long as everyone we talk to keeps throwing the hot potato to someone else, we feel like we are screaming in the desert. Fundamentally, it is not a matter of finding a single perpetrator of sexism. In such matter, there is a nebula of responsibility which, altogether, allow for these things to happen. Either one of these three actors could have, alone, changed the situation for the better and prevented the (re)production of discriminatory practices.

Gender equality: such a distraction

This dispute also provided an illustration of the strategy that consist in treating women’s denunciation of gender inequalities as mundane and marginal. The men’s captain described the event event as an unnecessary “distraction”, while the groundsman had reduced it to a woman’s “moaning”. There were also repeated allusions to the fight for gender equality being “our cause”, i.e. a women’s problem, as opposed to a men’s problem or a problematic feature of the world of football or university sports at large.

Perhaps most baffling is the capacity to simultaneously profess support for gender equality while choosing to focus on criticizing the specifics of women’s stances – typically their tone or formulation. This has the effect of undermining women’s critical voices and sense of legitimacy while preserving progressive and gentlemanly appearances – a form of elegant and all-too-trendy back-stabbing. The men’s FC and the footballers were explicit on their ideological alignment with gender equality. This, however, always came with a “but…” and rarely (if ever) with any kind of positive action to actually turn this support into anything tangible that would have helped us.

Allies and actions. Hint: it’s not mansplaining

Yet as we reflect on all this, it does seem clear to us that a lot of people probably did want to help, even among those we took issue with. The question of how men – or anyone – can be allies rather than opponents in the fight for gender equality is a tricky but essential one. Some answers are already being explored at the LSE, for instance in the futsal club.

The futsal committee has been adamant, in the last couple of years, that they wanted the club to include women and women competing, and they have been putting a rather colossal amount of energy into launching and bolstering the women’s team this year. A futsal alumni became the women’s coach; the futsal committee and many male futsal players attended most of the women’s matches, with the women’s cup finale gathering up a little crowd of supporters. It was their initiative to come support the women’s team and they expressed immoderate, unironic enthusiasm and interest in the games – an experience nothing short of extraordinary for women used to British university football.

The events organized by the futsal club also reflected this emphasis on diversity and inclusion. They went from encouraging mixedness (at the Futsal World Cup Challenge in the Michaelmas Term) to requiring it (at the interdepartmental futsal tournament last week). The participation of the club to the ICE London Conference in February also saw the committee convincing the organisers to have one day dedicated to mixed rather than only all-male football games. They chose to send a mixed team to the Prague tournament, which had previously (like the club) been all-male.

The fact is that all-male environments such as segregated sports clubs are prone to becoming prime terrain for toxic masculinity – which is bad for everyone, both men and women. Many male futsal players thus mentioned the “lad mindset” in the men’s football club as a factor in their decision to join futsal rather than football. Implementing gender-mixedness and gender equality in clubs, at trainings, at tournaments and so on, is a way of neutralising this and it helps overcome prejudices.

Conclusion

Expressly inviting women, supporting them and valuing them is a wonderful change, one that we need in order to make male-dominated sports more open and, well, less toxic. Additionally, there is a pressing need for men to start making gender equality their problem, and to start tackling these issues from their own accord instead of always leaving women alone in the front line.

We will be playing; we will get that pitch that we are entitled to; we won’t let discrimination, humiliation, and abuse go unchallenged. If you are a man, denounce them with us, and not only tacitly, not only when there’s no risks or consequences, or when nobody’s watching; talk to your team, to the groundsman, to the staff; make a public stance about it; organise a meeting on how to curb sexist and homophobic university sport culture; tell your mates that their comments are not ok; invite women to play at games and tournaments; go watch and cheer for women playing sports. Question sexism in all forms and shapes: question symbols and attitudes as well as abuse and insults. The LSE shouldn’t have a Football club and a Women’s football club. Nobody plays women’s football, or men’s football for that matter. We are women who play football, rugby and whatever else we fancy, and we belong here just as much as the men do.

A longer version of this article is available on LSE newspaper The Beaver’s website. It includes interviews with LSE players, coaches and club captains.