The shift in global economic activity towards the thriving economies of South and East Asia will ‘determine where the golden opportunities of the future will be and where we must be too’. This was the position communicated by Liam Fox, the UK Secretary of State for International Trade and the President of the Board of Trade, on 27 February 2018.

Fox’s rhetoric reflects a wider theme in the UK government’s foreign policy since 2010: economic power has shifted from the West towards East Asia. But the Secretary’s pronouncement risks being understood — once again — to refer primarily to opportunities associated with India and China. By not explicitly mentioning Southeast Asia, Fox has intensified the question of how London will approach this region in the future.

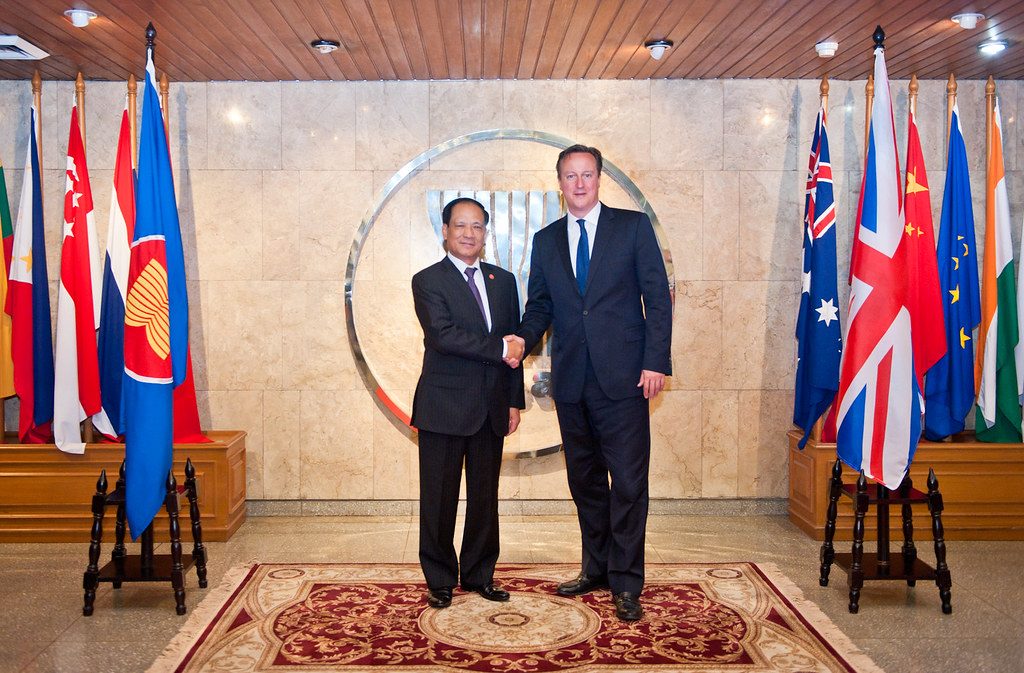

UK Prime Minister David Cameron’s visit to ASEAN in June 2015 (Source: ASEAN, 2015)

The United Kingdom has longstanding security and economic interests in Southeast Asia. London is a member of the Five Power Defence Arrangements and has a residual military presence in Brunei. Two-way trade with Southeast Asia may only constitute a fraction of the United Kingdom’s trade with Europe but it still amounted to £32.4 billion (US$45 billion) in 2016 — a 9.1 per cent increase from 2015. The United Kingdom’s main trading partner in the region is Singapore, through which trade with other ASEAN states is often routed.

Beyond its bilateral ties, London’s relationship with ASEAN is mediated through the European Union, one of ASEAN’s most generous dialogue partners. The EU has an enhanced dialogue partnership with ASEAN, currently geared towards supporting ASEAN Community-building. With the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU approaching, London has to decide whether it wants a formal partnership with ASEAN — and, if so, what kind of arrangement. The ASEAN Charter lists possible options, including full dialogue partner, sectorial dialogue partner or development partner.

The ideal scenario for London would be a simple transition from being part of the EU–ASEAN dialogue partnership to enjoying the status of full dialogue partner on its own. This is not very likely.

ASEAN imposed a moratorium on awarding dialogue partner status in 1999 to consolidate its existing dialogue relationships in the wake of the Asian financial and economic crisis. If the status of dialogue partner is not, or is not immediately, available, the United Kingdom may consider applying for development partner status (as Germany did). It could also argue in favour of negotiating a ‘bespoke’ partnership that better takes account of the United Kingdom’s entire range of links, interactions, interests and contributions vis-a-vis the region.

The initiative for any formal relationship needs to come from London as ASEAN is unlikely to map out a pathway for the United Kingdom to work towards a formal relationship. But a call for a ‘bespoke’ arrangement in name might lead to raised eyebrows because it is probably not clear to all ASEAN members why London should receive a special formal relationship status. To attain such status London may also be asked to first demonstrate its commitment to ASEAN’s goals through further substantive cooperation and sustained engagement.

The initiative for any formal relationship needs to come from London…

London must also decide whether to prioritise slowly building a formal partnership with ASEAN or to initially focus on greater economic opportunities. Having a formal partnership with ASEAN will not necessarily guarantee that the United Kingdom’s trade prospects dramatically improve. Greater trade in goods is not always dependent on a free trade agreement (FTA), which often do not remove non-tariff barriers, especially given that the UK has strong service export industries.

Still, the United Kingdom is positioning itself as a country that is keenly interested post-Brexit in exploring FTAs with relevant trading partners beyond Europe to meet its prosperity interests. Pursuing this objective in Southeast Asia is not straightforward, but possible choices include focusing on bilateral FTAs with selected ASEAN states, the long-term vision of an ASEAN–UK FTA and London joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Since the concluded but long-stalled EU–Singapore FTA might enter into force before the United Kingdom exits the EU, London may be able to ‘grandfather’ an existing deal. Singapore is unlikely to object. Singapore is currently the United Kingdom’s largest trading partner in Southeast Asia and one of the few Asian countries where the United Kingdom has a trade surplus in goods and services.

…the United Kingdom’s market share in goods is now falling behind Germany and France in some Southeast Asian countries…

While statistics hide many truths, they do show that the United Kingdom’s market share in goods is now falling behind Germany and France in some Southeast Asian countries. Since improved market access in ASEAN states will remain of interest to London, focusing on the CPTPP might be a logical step. But aside from the question of whether joining this arrangement is politically feasible, it remains unclear whether significant investment into such a move would be compatible with quickly building a partnership with ASEAN.

As the United Kingdom exits the EU, the challenge will be to develop a coherent policy towards Southeast Asia that takes account of the United Kingdom’s wider geopolitical and security interests, while strengthening its economic ties with Southeast Asia — a market of over 640 million people. The United Kingdom must also balance a long-term strategy for engaging ASEAN with the high-profile pursuit of new FTAs.

* This article was originally published on East Asia Forum

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

1 Comments