“COVID-19 has been met with economic protectionism and the tightening of borders. Some companies are already re-shoring BPO activities, taking advantage of newly unemployed workforces in places with a wider penetration of broadband and home office equipment, and where impacts of future lockdowns are more predictable”, writes Dr Maddy Thompson, Postdoctoral fellow at the University of Keele.

_______________________________________________

The Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry is one of the Philippine economy’s two primary ‘legs’, contributing $26 billion to the Philippine economy in 2019. BPO employs 1.3 million people in over 1000 firms. Workers provide services for overseas corporations including facilitating travel and insurance cover, customer support for technology, and telehealth services. BPO activities have been exempt from closure during quarantine periods. However, the closure of public transport leaves many employees unable to travel to work. Insufficient home internet connectivity leaves others unable to work from home. COVID-19 has disrupted the BPO industry and the overseas corporations it serves.

BPO in the Philippines

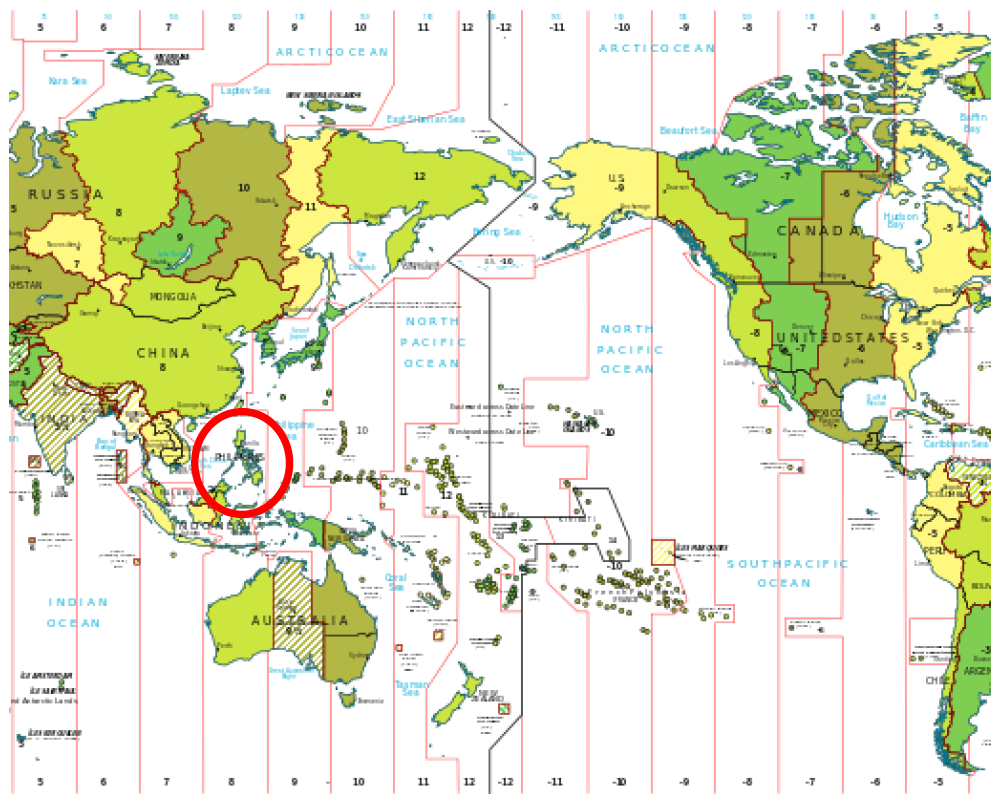

The Philippines’ BPO industry began in earnest in the 1990s, its growth was facilitated by “overly optimistic” government support (Soriano and Cabañes, 2020). Its contribution to the Philippine economy is now second only to remittances brought in via migration. The industry is oriented to the country’s former colonial power, the USA, and also serves Europe and nearer neighbours, Japan, New Zealand, and Australia (see Figure 1). More recently, the rise of digital platforms has facilitated freelancing. Here, rating systems and global competition creates a highly competitive and uncertain industry (Wood et al., 2019). There are an estimated 1.5 million Filipino freelance workers on these platforms.

Figure 1: A partial world map showing time zones (Poulpy, 2012). The Philippines, circled in red, is well placed to serve Japan, Australia and New Zealand. Serving US and European Customers requires later shifts.

The Philippines has the world’s largest concentration of call centre workers, but India has the bigger BPO market. India successfully markets key cities as hubs of innovation, whereas the Philippines takes on back-end work that is ripe for automation. Though the IT and Business Process Association of the Philippines has tried to attract more highly skilled work, just 15% of the BPO workforce were employed in such roles before the pandemic. Indeed, Manila’s overall ranking, second on the Tholons list of Top Super Cities for Digital Innovation (see Table 1), reflects the fact that there is a well-established BPO industry, rather than a culture of digital innovation.

Table 1: Top Super Cities for Digital Innovation according to Tholons (2019).

BPO expansion is linked to and facilitated by the mass emigration of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) and Philippines’ legacy of colonialism (Thompson, 2019). OFWs and BPO workers succeed in the global labour market for the same reasons (Soriano and Cabañes, 2020). STEM subjects are largely taught in English with western content and skills (Ortiga, 2017) while keeping in touch with migrant family members means Filipinos are used to digital and distanced communication (McKay, 2016).

For example, the Healthcare Information Management (HIM) sector takes advantage of the estimated 200,000 under- and unemployed nurses in the Philippines (Thompson, 2019). Global North governments and businesses have long encouraged the Philippines to train nurses beyond demand (Masselink and Lee, 2010; Ortiga and Macabasag, 2020). Now, faced with increasing pressures on healthcare systems, rising anti-migration sentiment, and technological advances, outsourcing healthcare via digital platforms is increasingly attractive (Thompson, 2019). Through incorporating this ready-made, low-cost, highly skilled workforce into the digital economy, profit margins in the global North increase. Outsourcing, however, restricts the material benefits migration can bring for individuals and their families.

BPO workers in the Philippines have variable employment experiences. For permanent employees, BPO roles offer relatively high pay, working benefits (i.e., health insurance), and safe, air-conditioned working environments (Thompson, 2019). As the industry has grown, however, pay and conditions have declined, with an estimated two-fifths of the workforce now employed on ‘floating’ / ‘no-work-no-pay’ status. Often, workers are forced onto such contracts and protests have ensued (Figure 2). Floating workers are not eligible for working benefits. This is particularly problematic for the 53.2% of women BPO workers who are more likely to have caring duties. Additionally, Wood et al. (2019) found that Filipino online freelancers have few legal labour rights. Nonetheless, comparatively high pay means BPO and freelance work is viewed as “good” by Filipinos (Soriano and Cabañes, 2020).

Figure 2: In 2017, Sitel BPO workers protested in Cebu after their contracts were changed to ‘floating status’ (BIEN, 2017).

Responding to Covid-19

The Philippines imposed a nation-wide lockdown, Enhanced Community Quarantine, from 16th March 2020 (Ocampo and Yamagishi, 2020). While this has been relaxed in some regions, urban areas, home to BPO offices, have been most affected and experience stricter lockdowns. During periods of Enhanced Community Quarantine, BPO is one of few industries allowed to remain open, demonstrating its importance to the country’s economy and geopolitical interests. However, quarantine restrictions meant BPO businesses were unable to maintain normal staffing levels, particularly at the onset. Concurrently, global travel restrictions and national lockdowns elsewhere increased short-term demand for travel and insurance services. Businesses in other sectors pulled out.

Responses from the foreign businesses impacted vary. Some sought to facilitate homeworking, shipping IT equipment to workers’ homes. As the average Manila household has 4-5 people with “poor yet expensive internet connection” (Ocampo and Yamagishi, 2020: 8), homeworking is unsuitable for many. Others businesses provided on-site accommodation to allow workers with quarantining family members or those without caring duties to continue to work and be paid. Workers report this ‘accommodation’ includes sleeping at work-stations or sharing hotel rooms without Covid-19 positive workers being separated out.

Figure 3: A typical call centre layout in the Philippines. Notes the difficulties for physical distancing if there was a full work-force (Marj1999, 2017).

Though permanent employees are entitled to sick pay, many have had their contracts changed to floating status. Overseas companies are unwilling to extend the same benefits to their Philippine workers as they have to domestic workforces. Workers who have been absent to self-isolate, care for family members, or been physically unable to work, have gone unpaid. Although freelancers already working from home are less likely to be infected, the work available to them has been reduced. As BPO workers are often primary breadwinners in their household, COVID-19 has the potential to plunge families into poverty.

Exploitation of BPO workers has been intensified and made more visible by the pandemic (see also Lawreniuk, 2020). Those unable to work are made disposable and left without financial security. Those who can work are placed in dangerous settings without proper precautions. The make-up of BPO workers in the Philippines places vulnerable groups at heightened risk of exposure to exploitative practices. Women have long dominated call centre activities, while BPO is one of the few workplaces where Filipino LGBTQ+ workers can find safe employment. Transgender women in particular have entered the industry in their thousands, mainly in call centre roles (David, 2015). Already vulnerable groups are thus at a higher risk of infection.

The pandemic has also made visible the global interconnections that shape BPO. In March, according to Sharwood (2020), Australian consumers were informed that:

Due to increased containment measures announced by the Philippines Government overnight, Telstra’s contact centre workforce has been reduced. […] there will be longer wait times for customers

Blaming the Philippine government and omitting concern for the workers shows how companies like Telstra absolve themselves of responsibility (see also Brydges and Hanlon, 2020). Overseas firms are unlikely to initiate longer-term efforts to support their BPO workers.

In the Philippines, these connections are also evident. Many BPO workers have become infected and BPO offices have been identified as hubs of community transmission nationwide. In smaller urban areas such as Bacolod, this has led to public harassment and discrimination towards BPO workers. The same is true for returning OFWs who are associated with local outbreaks. BPO workers and migrants are being transformed from national heroes to vectors of disease. Through serving the world, the Philippines vulnerability to the effects of Covid-19 is heightened.

BPO post-pandemic

COVID-19 has been met with economic protectionism and the tightening of borders. Some companies are already re-shoring BPO activities, taking advantage of newly unemployed workforces in places with a wider penetration of broadband and home office equipment, and where impacts of future lockdowns are more predictable. COVID-19 could therefore accelerate the de-globalisation of work (see also Niewiadomski, 2020). Combined with the expansion of automation and AI in multiple sectors that Covid-19 responses have prompted (Chen et al., 2020), the short-term future of the Philippines’ BPO industry is at risk.

Rapidly removing FDI from the Philippines will reveal the exploitation globalisation has produced. Already, the withdrawal of BPO companies is exposing vulnerable workers and their families to increasing precarity. The potential physical and mental health implications of transgender women being unable to afford or access medical services could be devastating. COVID-19 is also expected to tighten border controls and thus ‘throttle’ labour migration (Abel and Gietel-Basten, 2020). Already remittances from migrants have been disrupted, and many migrants have been forced to return to the Philippines. Increased competition from returning migrants could further exacerbate the erosion of labour standards. This will have significant impacts on a nation dependent on migration and outsourcing.

Longer-term, business analysts predict that shifts in the acceptability of homeworking and the need for companies to cut costs due to the economic downturn could create gains in the outsourcing industry. As these gains are likely to be most prevalent for freelance work, this future would see the further reduction of tax revenues and workers’ rights (Wood et al. 2019). Other sectors that may survive are those where automation is less of a threat and demand is more stable. The Philippines’ HIM sector, for example, could see longer-term gains due to the highly skilled and in-demand nature of the work.

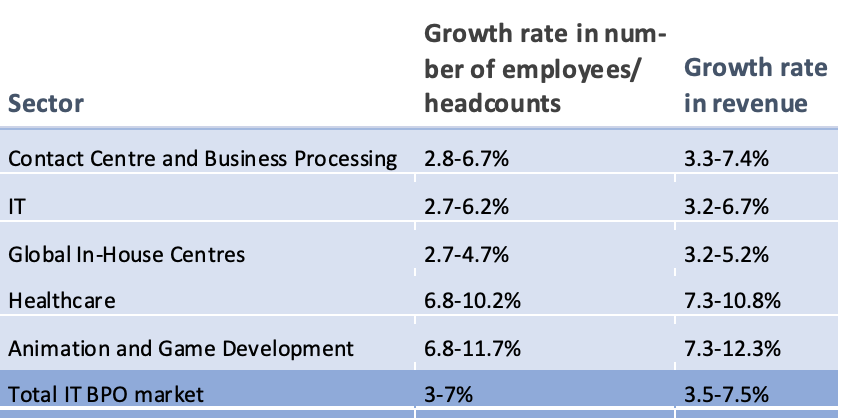

HIM workers are often required to have healthcare degrees and foreign healthcare professional registration. Workers undertake complex healthcare-related processes, including assessing medical information to approve or deny care, and engaging in telehealth patient outreach services to overseas patients (Thompson, 2019). The Philippines HIM sector primarily emerged in response to heightened demand for healthcare-related insurance processing activities generated by the USA’s (2010) Affordable Care Act (Obamacare). HIM has expanded rapidly over the last decade, and before COVID-19, this growth was expected to continue (Table 2). With a world-leading reputation, the Philippines is well-placed to capitalise on the growth in digital health provision that COVID-19 has precipitated.

Six months into the global pandemic and Digital Health industry insiders estimate we have witnessed the equivalent of five to ten years expansion in digital health. Telehealth in particular has been a key strategy to maintain both COVID-19 related and non-COVID-19 care activities in the global North. While there are no guarantees the transformation to digital health will be permanent, the cost-saving benefits make it an attractive option for any healthcare provider. Industry insiders note that COVID-19 has transformed patient and healthcare providers’ perceptions as to the acceptability of digital health interventions. The cultural shift required for digital health to flourish has already occurred. There is thus an urgent need to question the ethical dimensions of shifting healthcare provision online and overseas.

Table 2: Projected Growth Rate of BPO sectors from 2019-2022 (IBPAP, 2019)

The future of BPO

BPO workers in the Philippines have been put at risk to avoid ‘longer wait times’ for consumers in the global North. Looking ahead, it seems likely changes will contribute to a general lowering of labour standards. Alternatively, insufficient infrastructure to facilitate largescale homeworking could prompt mass withdrawal of FDI, putting the future of the BPO industry and the livelihoods of its workers at risk. While early responses to Covid-19 described a global “resurgence of reciprocity” (Springer, 2020), BPO work shows how COVID-19 intensifies and makes visible enduring forms of global exploitation. Left unchecked, corporate responses to COVID-19 will further heighten inequalities in an already unequal world.

Tracking the accelerated move to digitally facilitated healthcare, attention has largely focused on the ability for big data to shape responses and map COVID-19 (Brice, 2020; Desjardins et al., 2020; Rosenkrantz et al., 2020), concerns about security, surveillance (Datta, 2020), and misinformation (Stephens, 2020), and the impact of COVID-19-specific technologies on urban spaces (Chen et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2020; James et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020). We must, however, attend to questions of global justice.

How will shifts towards digital health in the developed world impact the developing world? Are we witnessing the rise of AI and robotics replacing BPO workers, or the further entrenchment of overseas corporations in the Philippines? Increases in outsourcing would benefit the Philippines but simultaneously exacerbate its vulnerability and dependency. Workers may have more stable work, but with highly uneven healthcare provision in the Philippines, having trained healthcare professionals serving the needs of places with better standards of health raises critical ethical concerns.

References

Abel, G., J., Gietel-Basten, S., 2020. International remittance flows and the economic and social consequences of COVID-19. Environ Plan A 0308518X20931111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20931111

Barnett, A., 2020. Out of the Belly of Hell: COVID-19 and the humanisation of globalisation. openDemocracy. URL https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/out-belly-hell-shutdown-and-humanisation-globalisation/ (accessed 8.11.20).

Baynham, D., Hudson, M., 2020. Rollout of video consultation across general practice. Technology in the NHS. URL https://healthtech.blog.gov.uk/2020/03/26/rollout-of-video-consultation-across-general-practice/ (accessed 7.8.20).

Brice, J., 2020. Charting COVID-19 futures: Mapping, anticipation, and navigation. Dialogues in Human Geography 10, 271–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620934331

Brydges, T., Hanlon, M., 2020. Garment worker rights and the fashion industry’s response to COVID-19. Dialogues in Human Geography 10, 195–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620933851

Chen, B., Marvin, S., While, A., 2020. Containing COVID-19 in China: AI and the robotic restructuring of future cities. Dialogues in Human Geography 10, 238–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620934267

Choi, J., Lee, S., Jamal, T., 2020. Smart Korea: Governance for smart justice during a global pandemic. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 0, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1777143

Datta, A., 2020. Self(ie)-governance: Technologies of intimate surveillance in India under COVID-19. Dialogues in Human Geography 10, 234–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620929797

Desjardins, M.R., Hohl, A., Delmelle, E.M., 2020. Rapid surveillance of COVID-19 in the United States using a prospective space-time scan statistic: Detecting and evaluating emerging clusters. Applied Geography 118, 102202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102202

IBPAP, 2019. THE PHILIPPINE IT-BPM INDUSTRY GROWTH FORECAST (2019-2022).

James, P., Das, R., Jalosinska, A., Smith, L., 2020. Smart cities and a data-driven response to COVID-19. Dialogues in Human Geography 10, 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620934211

Lawreniuk, S., 2020. Necrocapitalist networks: COVID-19 and the ‘dark side’ of economic geography. Dialogues in Human Geography 10, 199–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620934927

Marj1999, 2017. English: BPOSeats.com has positioned itself to be the #1 BPO Solution, Call Center Office, Serviced Office and Seat Leasing option in Cebu, Philippines by providing our clients with the most highly experienced, dedicated employees coupled with our brand new PEZA accredited facilities that use only the fastest 100mbps+ FIBER OPTIC Internet Connections available at the most affordable prices around.

Masselink, L.E., Lee, S.-Y.D., 2010. Nurses, Inc.: expansion and commercialization of nursing education in the Philippines. Soc Sci Med 71, 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.043

McKay, D., 2016. An Archipelago of Care: Filipino Migrants and Global Networks. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Niewiadomski, P., 2020. COVID-19: from temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tourism Geographies 22, 651–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757749

Ocampo, L., Yamagishi, K., 2020. Modeling the lockdown relaxation protocols of the Philippine government in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: An intuitionistic fuzzy DEMATEL analysis. Socioecon Plann Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2020.100911

Ortega, A., 2020. The deglobalisation virus. ECFR. URL https://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_the_deglobalisation_virus (accessed 7.8.20).

Ortiga, Y.Y., 2017. The flexible university: higher education and the global production of migrant labor. British Journal of Sociology of Education 38, 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1113857

Ortiga, Y.Y., Macabasag, R.L.A., 2020. Temporality and acquiescent immobility among aspiring nurse migrants in the Philippines. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 0, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1788380

Poulpy, 2012. English: Timezones in the world, 2012, centered on the Pacific Ocean.

Reed, J., Ruehl, M., Parkin, B., 2020. Coronavirus: will call centre workers lose their ‘voice’ to AI? The Financial Times.

Rosenkrantz, L., Schuurman, N., Bell, N., Amram, O., 2020. The need for GIScience in mapping COVID-19. Health & Place 102389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102389

Soriano, C.R.R., Cabañes, J.V.A., 2020. Entrepreneurial Solidarities: Social Media Collectives and Filipino Digital Platform Workers: Social Media + Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120926484

Springer, S., 2020. Caring geographies: The COVID-19 interregnum and a return to mutual aid. Dialogues in Human Geography 10, 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620931277

Stephens, M., 2020. A geospatial infodemic: Mapping Twitter conspiracy theories of COVID-19. Dialogues in Human Geography 10, 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620935683

Suau-Sanchez, P., Voltes-Dorta, A., Cugueró-Escofet, N., 2020. An early assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on air transport: Just another crisis or the end of aviation as we know it? J Transp Geogr 86, 102749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102749

Terry, W.C., 2014. The perfect worker: discursive makings of Filipinos in the workplace hierarchy of the globalized cruise industry. Social and Cultural Geography 15, 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2013.864781

Thompson, M., 2019. Everything changes to stay the same: persistent global health inequalities amidst new therapeutic opportunities and mobilities for Filipino nurses. Mobilities 14, 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2018.1518841

Wood, A.J., Graham, M., Lehdonvirta, V., Hjorth, I., 2019. Networked but Commodified: The (Dis)Embeddedness of Digital Labour in the Gig Economy: Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038519828906

Zeng, Z., Chen, P.-J., Lew, A.A., 2020. From high-touch to high-tech: COVID-19 drives robotics adoption. Tourism Geographies 22, 724–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1762118

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Your artcles are impactive to the welfare of Overseas Filipinos (OFW/Overseas Filipino residents) & their families in the Philippines. I hope that they reach the government agencies responsible for them so that positive actions should be made and effectively implemented.

good thing is that these BPOs are also providing medical assistance to their employees.. https://rafi.org.ph/focus-areas/micro-finance/