“The Duterte government’s militarist approach has failed to slow down the spread of the virus. Even with the imposition of one of the longest and harshest lockdowns in the world, the Philippines as of 16 August 2020 has the highest number of total COVID-19 cases in Southeast Asia, making it the region’s disease hotspot”, writes Dr Roderick Galam, Senior Lecturer in Sociology at Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

_______________________________________________

The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated the already grim conditions that many young people around the world are facing (Costa Dias et al., 2020; Programme on Youth Unit, 2020). It presents a triple threat to youths: disruptions to their education, training and work-based learning; heightened challenges for young jobseekers and new entrants to the labour market; and loss of job and income accompanied by the deterioration of the quality of employment (ILO, 2020a: 1; ILO, 2020b). I examine in this essay how the coronavirus crisis will further delay the transition from education to work and to social adulthood of thousands of male Filipino youths aspiring to become seafarers in the merchant fleet of the global maritime industry. These transitions are entwined with international labour migration, which the pandemic has severely disrupted, causing these young Filipinos to lose arguably their only opportunity to get a job and reach adult status. The Philippine state’s mismanagement of the pandemic; the impact of the current crisis on the global maritime industry; and the repercussions on the shipboard training opportunities for Filipino maritime students have created a perfect storm that has led to the immobility of these Filipino youths both in terms of international migration and life-course transitions.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Philippine Situation

President Rodrigo Duterte’s response to the crisis has damaged the economy, worsening the country’s poverty and unemployment situation (Suzuki, 2020). By the end of May 2020, the Philippine economy had lost around 2.2 trillion pesos or USD 44 billion (De Vera, 2020). In the second quarter of 2020, it contracted by 16.5 per cent (Figure 1), plunging the country into its first recession in three decades since comparable records began in 1981 (De la Cruz and Morales, 2020).

Figure 1: GDP Growth Rate of the Philippines, 1982-2020. Philippine Statistics Authority, JC Punongbayan

A close examination of the April 2020 Labour Force Survey, which counted only 7.25 million workers as unemployed, showed that up to 90 per cent of the country’s labour force were fully or partially displaced by the March to May lockdown: 50 per cent (22.5 million workers) did not work and 40 per cent (18 million workers) went from full-time to part-time employment (Lim, 2020). The global economic and labour market devastation caused by the pandemic has led to the mass retrenchment and displacement of more than 400,000 overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) whose remittances the Philippines has depended on to keep its economy afloat. It is predicted that OFW remittances—USD 33.5 billion in 2019 and equivalent to around 10 per cent of the Philippines’ GDP and 35 per cent of financial flows to the country (Almendral, 2020) could decline by 20.2 per cent (Takenaka et al., 2020).

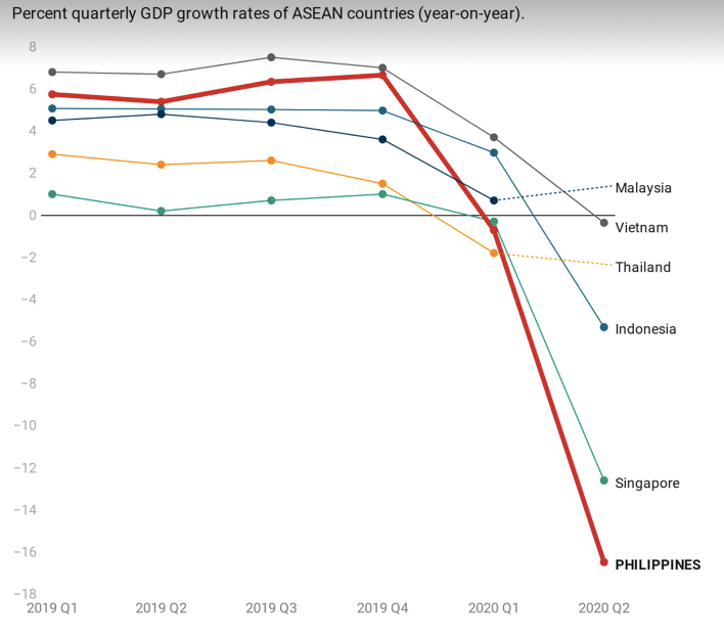

Prior to the pandemic, the Philippines was one of Asia’s fastest-growing economies. Its GDP growth rate of -16.5 per cent for April-June 2020 now makes it the worst economic performer among major ASEAN economies (Figure 2).

Figure 2: GDP Growth Rates of Major ASEAN Economies, 2019-2020 (as of 6 August 2020). Philippine Statistics Authority, Trading Economics, Rappler, JC Punongbayan.

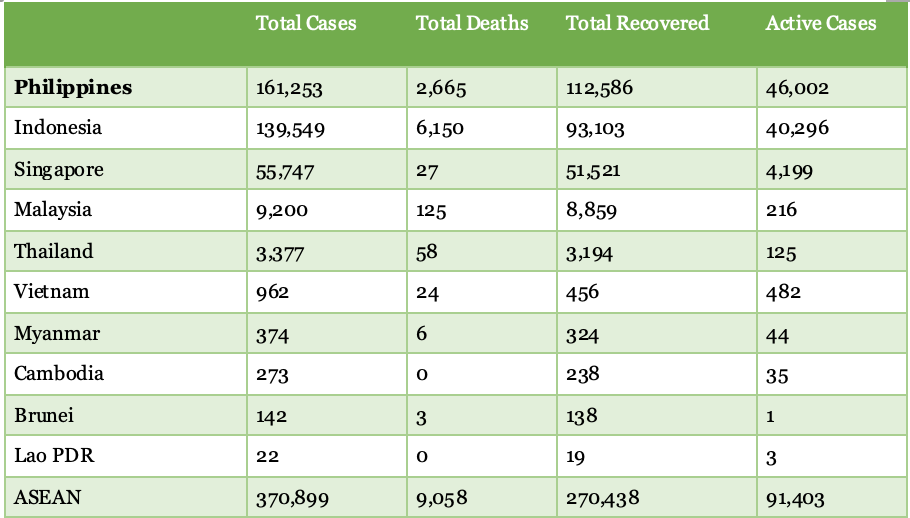

The Duterte government’s militarist approach has failed to slow down the spread of the virus. Even with the imposition of one of the longest and harshest lockdowns in the world, the Philippines as of 16 August 2020 has the highest number of total COVID-19 cases in Southeast Asia, making it the region’s disease hotspot (see Table 1). President Duterte’s incompetent handling of the pandemic has made the Philippines both the region’s sickest country and weakest economy (IBON, 2020). I will discuss below the consequences of Duterte’s failure to contain the virus on the spatial and temporal mobility of aspiring Filipino seafarers.

Table 1: Confirmed COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in Southeast Asia, as of 16 August 2020. The ASEAN Post

COVID-19 and Maritime Education in the Philippines

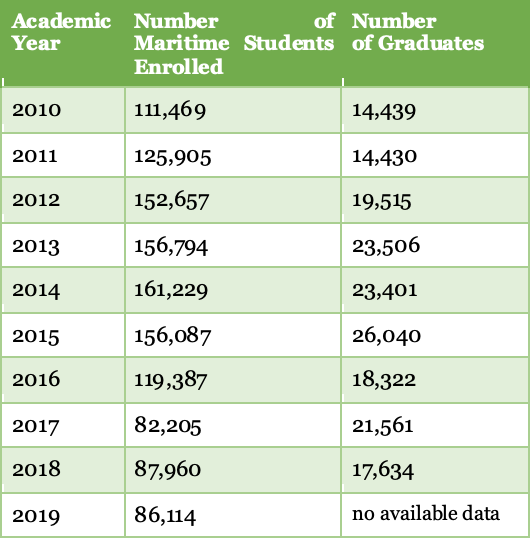

From 2009 to 2018, annual enrolment in maritime higher education institutions (MHEIs) in the Philippines averaged 124,000 students. This oversupply led to would-be seafarers competing for a limited number of cadetship positions and jobs. Consequently, only a small percentage of the total of enrolled students manage to graduate with a bachelor’s diploma (Galam, 2018a). From 2014 to 2018, only 106,958 (17.62 per cent) of all 606,868 enrolled students completed all classroom-based learning in the first three years (Table 2). On average, each year only 15 per cent of those who completed the three years managed to complete their final, fourth year to obtain either a BS Marine Transportation or a BS Marine Engineering degree (Vingson, 2019).

Table 2: Maritime Education Enrolment and Graduation Figures, 2010-2019. Commission of Higher Education, Philippines.

The low success or completion rate in maritime education could indicate the small number of cadetship positions available to students to complete twelve months of shipboard training. Thousands of maritime students have to wait years for their turn to board a ship, with many of them opting to accept salaried low-level ratings positions that require them to complete 36 months of shipboard experience. Without this training, these students have no chance of working in the global maritime industry and, with very few alternative employment paths, would most likely work in low-paid temporary jobs that offer no security.

My research shows that there is an overwhelming preference among students to undertake this training aboard ships in the international fleet because some manning agencies would not recognise training done in the Philippine domestic shipping sector as it does not always provide the kind of experience that international shipping does. Students aspire to work in international seafaring as the salary of the lowest-ranked seafarer is at least six times more than that of locally employed workers (Galam, 2018b). With the deep recession, the COVID-19 pandemic has plunged the global economy into, training positions for maritime students and aspiring seafarers have become or will become even more limited as they will be the least of the priorities of shipowners or principals looking to cut costs and reduce losses. This situation, combined with the ongoing crew change crisis, will further delay the training of maritime students. Indeed, one of the Philippines’ best maritime schools, which has the strongest ties to international shipowners and shipping companies and hence perhaps the highest number of sponsored cadets, has already restructured the curriculum of some of these students by delaying their shipboard training by one year.

Aspiring Filipino Seafarers Stuck and Besieged on All Sides

The most affected among all Filipino maritime students by the global economic downturn’s impact on the global maritime industry and the Duterte government’s failure to contain the spread of COVID-19 are those who have no sponsorship from international shipping associations and shipping companies. To ensure that they have access to a steady supply of competent seafarers, international shipowners and shipping companies have established sponsored cadetship programmes with the best MHEIs in the Philippines. These programmes pay for the education of these students and guarantee them a ship for their shipboard training (Galam, 2018a). According to a maritime industry insider who has requested anonymity, there are about 1,480 sponsored cadetships. If we take 3,209—the average completion number from 2014 to 2018 as baseline figure for the number of shipboard positions available—and deduct 1,480 sponsored cadetship positions, then only 1,729 positions remain for more than 19,900 students to compete for. (The average annual graduation figure from 2014 to 2018 is 21,391). These available positions will likely be reduced as cadetship positions get cut down.

How then have unsponsored students, whose number increases cumulatively over the years, obtained a placement on a ship? The strategy many, if not most, have employed is by working for free for manning agencies. I have called this form of unpaid labour and servitude as ‘utility manning’ (Galam, 2018c) on account of these ‘volunteers’ being called ‘utility men’ or ‘utility boys’ (gofer or flunkey). They undertake clerical and janitorial tasks; do domestic work like cooking, cleaning, washing and ironing clothes; and look after babies and small children for the agency owners and their families. Many others scout for seafarers their agencies urgently need or liaise with embassies for the transit visa applications of seafarers hired by their manning agency. Their utility manning could last for a few months or more than two years (Galam, 2018c).

While working for free for manning agencies, utility men are financially supported by their families. The loss of livelihoods of millions of Filipinos, including overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) as a result of the pandemic and the imposed restrictions to mobility will make it challenging for many families to continue supporting these young men. Since Luzon, the Philippines’ biggest island and where Metro Manila is located, was put under total lockdown on 16 March, utility men have not been able to work for their much-desired ship placement as the almost 500 manning agencies, all located in Manila, conducted their activities online. Many of these utility men come from outside Metro Manila and poor backgrounds. Some of them probably managed to go home before the imposition of the lockdown but it is very likely that many of them were stranded in the capital region. Given their financial situation, the hardship they have faced since is unimaginable.

With the continuing rise of COVID-19 cases in the Philippines, with 56 per cent or 100,456 of the country’s total infections recorded in Metro Manila (ABS-CBN News, 2020), it is highly unlikely that these utility men will be able to resume their ‘utility manning’ quickly or at all. Even if manning agencies resumed normal operations, social distancing measures will require them to reduce the number of people inside their offices. Utility manning opportunities will most likely be scaled down with many utility men likely to be let go with only the promise that they could go back if and when the situation became more favourable.

Those who are able to return to Manila will face extreme difficulty in finding suitable accommodation. Days before the lockdown, many dormitories where they were staying, which especially catered to seafarers, utility men, and prospective and returning overseas migrant workers, shut down. Based on my fieldwork, these dormitories usually had around twelve (sometimes even more) people to a room. If these dormitories were to re-open and observe proper social distancing measures, such numbers of occupants per room would be untenable. Accommodation costs will certainly become more expensive and unaffordable to already financially struggling aspiring seafarers. Not only will getting from one place to another in Metro Manila to do their work as utility men be difficult and unaffordable because of limited and prohibitive public transportation (Butuyan, 2020), It will also be risky to their lives because COVID-19 cases continue to increase.

These conditions that restrict these young men’s spatial mobility add to the temporal dimensions of the pandemic’s impacts on their mobility. Their temporary loss of access—utility manning—to ship placements will delay their becoming seafarers. The likely decrease in cadetship positions and other opportunities to gain shipboard experience will further prolong this delay. Before COVID-19, many utility men had to work for more than two years before being allocated a ship and spend several months or more than a year looking for a manning agency to work for. Stuck, hanging on to futures that are put on hold, these aspiring Filipino seafarers will have to wait longer for their chance at international labour migration that will enable them to get a job, become financially independent, support their family rather than be supported by them, and attain social adulthood.

References

Alderton, T., and N. Winchester. 2002. Globalisation and deregulation in the maritime industry.” Marine Policy 26 (1): 35–43.

Almendral, A. 2020. Crucial yet forgotten: The Filipino workers stranded by Coronavirus. Nikkei Asian Review, 15 July. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/The-Big-Story/Crucial-yet-forgotten-the-Filipino-workers-stranded-by-coronavirus.

Bockmann, M. 2020. Crew change costs shipowner $820,000, says ICS. Lloyd’s List, 7 August. https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1133432/Crew-change-costs-shipowner-820000-says-ICS?fbclid=IwAR1Z2h46xepTYm8tyyX82P_zJmBjE50E-A3ZfMj6aStetP2iFC2T2vSQs1U.

Bowler, T. 2020. Seafarers in limbo as coronavirus hits shipping. BBC News, 16 April. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-52289303.

Chambers, S. 2020. Euronav: Crew change crunch is shipping’s ‘largest ever humanitarian and logistical crisis’. Splash 247.com, 6 August. https://splash247.com/euronav-crew-change-crunch-is-shippings-largest-ever-humanitarian-and-logistical-crisis/.

Costa Dias, M, Joyce, R, & Keiller, A. 2020. COVID-19 and the career prospects of young people. Institute for Fiscal Studies Briefing Note BN299. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/BN299-COVID-19-and-the-career-prospects-of-young-people-1.pdf.

De la Cruz, E & Morales, N. 2020. Philippines suffers first recession in 29 years, braces for grim year on virus woes. Reuters, 6 August. https://in.reuters.com/news/picture/philippines-suffers-first-recession-in-2-idINKCN2520AF.

De Vera, B. 2020. 2.2 trillion in losses: Cost of COVID-19 impact on PH economy. Philippine Daily Inquirer. 28 May. https://business.inquirer.net/298536/p2-2-trillion-in-losses-cost-of-covid-19-impact-on-ph-economy.

Galam, R. 2018a. An exercise in futurity: servitude as pathway to young Filipino men’s education-to-work transition. Journal of Youth Studies 21 (8): 1045-1060. DOI: 10.1080/13676261.2018.1442920.

Galam, R. 2018b. Women who stay: Seafaring and subjectification in an Ilocos town. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Galam, R. 2018c. Utility manning: Young Filipino men, servitude and the moral economy of becoming a seafarer and attaining adulthood. Work, Employment & Society 33 (4): 580-595. DOI:10.177/0950017018760182.

Hudson, P. 2020. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the maritime industry. Envistaforensics, 25 March. https://www.envistaforensics.com/blog/impacts-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-the-maritime-industry/.

IBON. 2020. Duterte gov’t to blame for worst economic collapse in PH history. IBON Organization, 6 August. https://www.ibon.org/duterte-govt-to-blame-for-worst-economic-collapse-in-ph-history/.

International Labour Organization. 2020a. Preventing exclusion from the labour market: Tackling the COVID-19 youth employment crisis. International Labour Organization Policy Brief. Geneva: ILO.

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_746031.

Lim, J. 2020. Covid-19 pandemic and the economy: Kulelat? Centre for People Empowerment and Governance Webinar: Governance failures during COVID-19 and alternative responses, 25 July.

McKay, S. 2007. Filipino sea men: Constructing masculinities in an ethnic labour niche. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33 (4): 617–633.

Suzuki, A. 2020. The Philippines’ response to COVID-19: Limits of state capacity. Kyoto University Centre for Southeast Asian Studies Corona Chronicles: Voices from the Field, 23 June. https://covid-19chronicles.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/post-046-html/.

Takenaka, A, Villafuerte, J, Gaspar, R & Narayanan, B. 2020. COVID-19 impact on international migration, remittances, and recipient household in developing Asia. ADB Briefs No. 148. http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/BRF200219-2.

Vingson, N. 2019. The current status of MET in the Philippines. Presentation at Philippine Association of Maritime Institutions 44th Annual Convention, February 22. Davao City, Philippines.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Really interesting, Roderick. Thank you so much for posting your understandings of how young seafarers’ lives are going to be affected for years by the pandemic. It’s tragic. Do you have any indication about whether it will be even harder for young women than for men?

Thank you Jo.