“The narrative of food commons assumes that food sharing is a material basis for transformation in a capitalist regime and an ideal force to democratic discourse. The narrative is powerful enough to refashion the mode of governance in a risk society.”, writes Gabriela Laras Dewi Swastika a full-time lecturer at the Faculty of Communication Science and Media Business at Universitas Ciputra Surabaya, Indonesia.

_______________________________________________

COVID-19 pandemic inhibits daily activity, even stops it for a moment. The effect is not only perceived on aspects of public health, environment, social issue, but also the economy. Many people are affected by the pandemic, it’s even harder for vulnerable groups. Vulnerable groups experience decreasing income, even some of them lose their jobs. Since March 2020 in Yogyakarta, there are collectives who have been engaging to provide food sources for affected people, yet donations have been opened and collected. They build public kitchens, prepare food granaries for villagers, and distribute meals. Some of the collectives are Dapoer Bergerak, Solidaritas Pangan Jogja, and Sama-sama Makan. In this circumstance, we can see that food sovereignty is key. If food ever understood as a commodity which has a given price so that it could be consumed, in this situation food becomes a commons—which is expected to be shared. Food as commons won’t exist without donations, or the flow of money, where the initiators can process food into ready-to-eat meals and distribute it to those who are in need. How is food then understood as the embodiment between commons and commodity? How do the collectives apprehend “gotong royong” or mutual help as a manifestation of local wisdom of people helping one another in Yogyakarta? How do the parties who initiate food sovereignty interpret commons in the midst of pandemic? Some of these questions can be answered through examining people narrative, thus narrative tells the strategy of inhabitants’ viability facing COVID-19 pandemic.

None of the people who live and inhabit in Special Region of Yogyakarta—better known as Yogyakarta (or Jogja), Indonesia—has escaped the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. In Indonesia, COVID-19 has become a pandemic since March 2020, when the first case was declared by the Yogyakarta provincial government on 15 March 2020. As of 22 August, more than 1,000 positive cases confirmed by the local government, 33 people died, and more than 800 persons being cured (Pemprov Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, 2020). Even though Yogyakarta, an area that experiences the most cases of COVID-19, has not been included in the red zone, Yogyakarta remains hit hard by this pandemic, especially because Yogyakarta is one of the main tourism destinations not only in the Java region but also in Indonesia. The COVID-19 pandemic cuts the economic chain in many sectors, varying from tourism and hospitality to informal and creative industries. The impact of the pandemic has been deeply felt by those who are vulnerable.

The economic gap in Yogyakarta is quite high. Statistics Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik) recorded the level of expenditure inequality of Indonesian population as measured by the Gini ratio was 0.380 in 2019. Meanwhile, the Gini ratio of Yogyakarta has surpassed this to reach 0.482 (Fauzia, 2020). This condition gets worse with the COVID-19 pandemic which causes the poor to become increasingly vulnerable. The tourism sector is now slow-moving, the informal sector becomes sluggish, and the arts and culture events, which are often held in Yogyakarta, no longer take place. Workers cannot earn their daily income to survive and creative workers also find it difficult to get artistic and cultural work projects at this time. On the other hand, assistance from the central government takes a long time to reach; when the distribution happens, it is not appropriately on target. Then how do they survive in this difficult time? How can they access food as one of the main components for surviving. If they don’t eat, how can they think clearly to overcome problems in the midst of a pandemic.

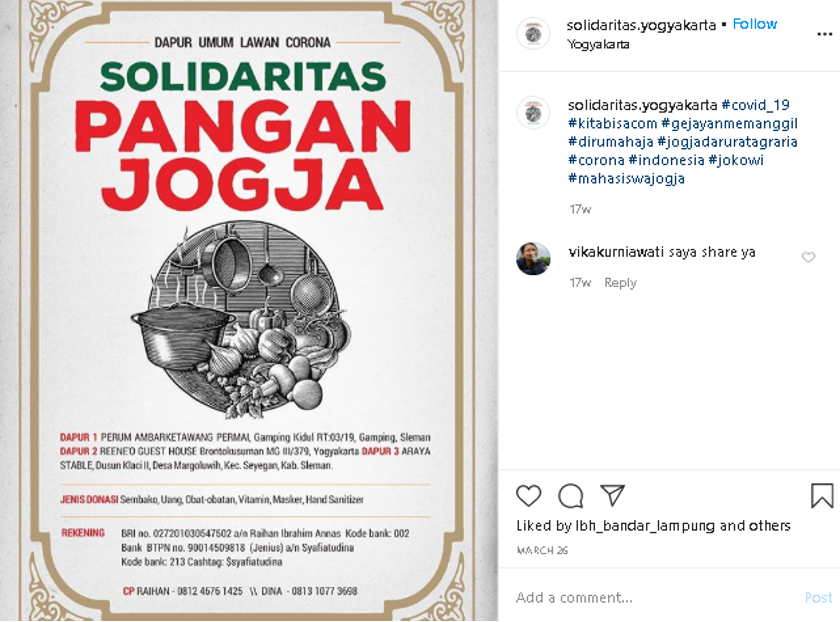

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the areas in Yogyakarta, collectives emerged and took initiatives to collect aids. They opened a voluntary donation channel so that they could buy comestibles (resources) and process them into ready-to-eat meals. Some of the notable collectives in Yogyakarta are Sama-sama Makan (“Together We Eat”), Solidaritas Pangan Jogja (“Jogja Food Solidarity”), and Dapoer Bergerak (“Motile Kitchen”). They focus their movement on producing nutritious ready-to-eat food and open public kitchens to prepare those meals. Sama-sama Makan provides food for creative workers who are affected by the pandemic. Dapoer Bergerak focuses on voluntary cooks and serves meals in a healthy and sustainable way, while Solidaritas Pangan Jogja navigates the partnership of people who are willing to open their private kitchens and maps food distribution.

These three collectives have similarities that underlie their work, namely: providing food that is easily accessible; working independently but still involving other people voluntarily; mapping and recording distribution of food; giving aid to the vulnerable groups. These collectives operate in the local area with resources that are close to each other. In addition, they can manage donation of money or raw food given by other donors. Sama-sama Makan, Solidaritas Pangan Jogja, and Dapoer Bergerak then no longer distribute aids in the form of money, which means that there is no exchange of value involved. What exists then is handing over the material forms (nutritious food) and use value of food for survival. The parties receiving help are vulnerable groups in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as poor families, labourers, pedicab (becak) drivers, small informal sector merchants, and daily workers, as well as creative workers (especially for Sama-sama Makan). What is distributed is not only ready-to-eat food; Dapoer Bergerak and Solidaritas Pangan Jogja also distribute food packages containing rice, eggs, cooking oil, milk for kids or toddlers, and groceries.

Figure 1: Dapoer Bergerak announced thier collected aid in April 2020. dapoerbergerak, 2020

Figure 2: Sama-sama Makan concerned about the affected creative workers. sama2makan, 2020.

Figure 3: Public kitchens opened by Solidaritas Pangan Jogja in March 2020. solidaritas.yogyakarta,2020.

In mapping distribution areas and targeting who deserved assistance, they have coordinated with public and private kitchens and listed affected groups. This mapping was carried out by the collectives usually using an online platform such as group chat and by conducting location survey with the help of local hamlet or neighbourhood administrators. The partnership promoted by this collective was not aimed at profits. Financial management was open because there were accountability reports shown to the public through their social media. Within the collectives, the idea of “gotong royong”, local wisdom that refers to “mutual help” also drove the solidarity action. itself is the idea created by founding fathers of Indonesia: it shows the decent and true spirit of being Indonesians. It is a form of mutual help and fair labour division which perennially dwelled on. Even though they were working together, a clear division of human resources was also needed: some focused on the meal procurement to be processed, some took care of the kitchen, some went to distribute food, and some made supplementary programmes and publications. Collectives used social media to disseminate information related to their activities, as well as specific information, including the use of the hashtag #RakyatBantuRakyat. Such dissemination of information was also aimed at making people know that they were independent: this was an independent movement that emerged from the initiatives of citizens (inhabitants) themselves and for the benefit of people.

From the Gramscian perspective, the value of hegemonic narrative raised by modern society can be attached to the concept of food as commodity, a dominant narrative held by the regimes of the contemporary industrial era (Vivero-Pol et al., 2019: 2). How we eat or how the food comes; raw materials of food; mode of production, distribution, consumption, the social context in which we eat food, even food packaging innovation, they are entirely political. It is called foodways. Foodways is a way of seeing food through its history and culture which was emerged from a network of production, distribution, and consumption (Young et al., 2015: 198). Today, the choice of what we eat is confronted by a contradiction: on the one hand, the consumption we do is driven by increasing individual agency opportunities, but on the other hand, the global system of spending on consumption, manufacturing, and exchange cost exploit human communities. The three main keys to addressing the foodways problem are production, circulation, and access (Swastika, 2018: 422).

The right to food is the right for every human being to maintain and develop their ability to produce the main food source and respect cultural diversity. It is also the right for each individual to be able to produce food in their own territory, hence food sovereignty is a precondition for the birth of food security. Food sovereignty is a discourse that emerged from the emancipation of citizens and their collaboration with various public and academic institutions. Food sovereignty talks about the rights for citizens as agents, individually as well as groups, to establish food policies; to maintain and regulate food production, and conduct interactions in the aim of achieving sustainability. Therefore, food citizens enable to determine the extent to which they survive and become self-reliant (Jarosz, 2014: 320). When Yogyakarta—and other cities in the world—were experiencing difficult times due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the question of the right to food became inevitable. To address the right to food and overcome vulnerability during COVID-19 pandemic, Dapoer Bergerak, Sama-sama Makan, and Solidaritas Pangan Jogja collectives adopted the food sovereignty approach.

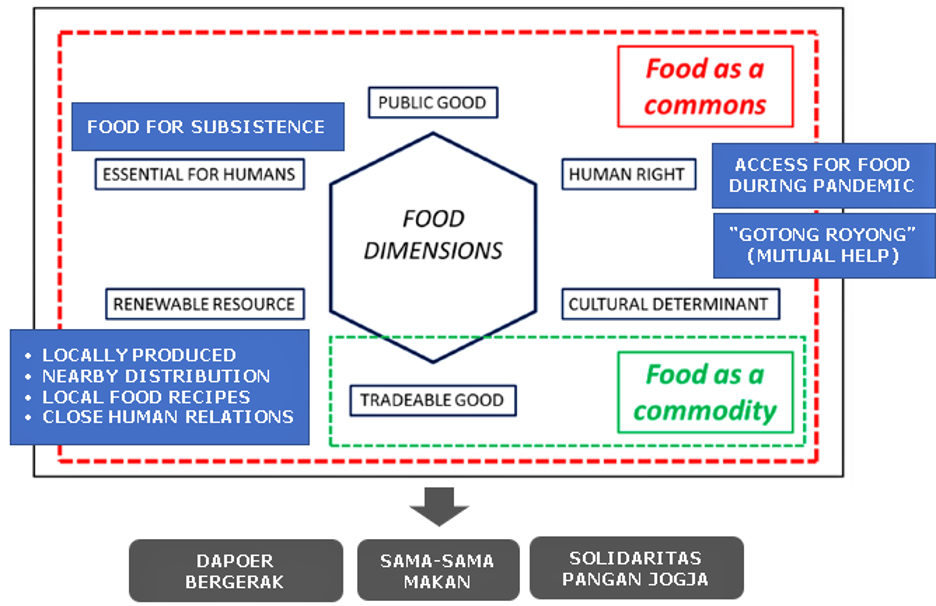

Food agency is restricted to the act of consuming, which is focused on losing the ability of agents (individually or collectively) to vital resources. In fact, everything related to food, be it collecting, capturing, harvesting, preparing, and consuming, represents a cultural act. In many countries, life revolves around food and there are shared values regarding how food is produced, distributed, and consumed. Food is also central to individual and community identity (Vivero-Pol et al., 2019: 14). This is the narrative that provides alternatives for transforming innovation for those who engage in non-dominant areas (niches). The narrative navigates three collectives not to define food as a commodity.

Figure 4: Food Dimensions. Vivero, et.al., 2019 (original version); Swastika, 2020 (blue boxes added)

What has been done by Dapoer Bergerak, Sama-sama Makan, Solidaritas Pangan Jogja is both resistant by rejecting commodification and transformative by processing donations to be returned as commons that can be accessed together. What they have been doing is questioning as well as unsettling the previously established industrial values, hegemonic commodity regime, and material function of the food itself. In this focus, what is meant by food as a commons is the way of food that can be accessed and processed for commoning purposes. The practice carried out by three collectives is referred to as “commoning”. Food as a commons is used both as a noun (as shared resources) and as a verb in term of commoning in which food is a common good. Food commons is known among a relatively small but influential cadre of professionals and activists intellectuals. Nevertheless, food sovereignty and food as commons are not always congruent. The former has a structural suggestion addressing production while the latter focuses on alternative nodes of governance to re-imagine access, use-value, and resource. Food commons is recalled as a form of unifying property. The various forms of commons are formed and demonstrated by a confluence of political allegiances—an association of congenial people who can be perceived as a collective, such as Dapoer Bergerak, Sama-sama Makan, and Solidaritas Pangan Jogja.

The call to make food as commons isn’t to be comprehended as a reaction to neoliberal capitalism, but as an internal and critical expression of liberal democracy. Can liberal democracy—an institution founded on private property and individual rights—promote a socialised property regime like food commons? Food as a commons narrative carefully questions the constitutional structure of the liberal state under corporate actors in the food chain. As an alternative, food commons offers a broader nuance of the communicative realm, not only in constitutional aspect but also extending to the discursive sources of order. The food commons, therefore, presents opportunities for discursive democracy for civil actors to demonstrate governance. The goal is to form a socialised and de-commodified food regime (Vivero-Pol, et al., 2019: 320).

Commons is also extended to the intangible aspects of social life, it is represented through creative works, cultural practices, and knowledge—in this case, we find when the collectives implement the idea of “gotong royong” (mutual help) on volunteerism and for non-profit work. Demonstrating the act of sharing is actually an asset for commons. The key to gotong royong as intangible commons is locality. In the midst of a pandemic that has become the issue of global modernity and as a result of the movement among people who have fused geographical boundaries, the collectives come up to answer the need for local resources and local access. Home-grown food resources are processed by the closest people who are bound by a sense of solidarity. They also offer alternative movement in the practice of commoning. Commoning practice suggests the rights of individuals who belong to the collective to access regulated usage by members; commoning may also differ between regions, seasons, or time span. Again, when we talk about the locality aspect, given its particular nature which the desired outcome is not predetermined but shaped by the relationships between the various members within the collective and those outside the collective—usually donors and volunteers. Mutual expectations among actors manifested through ethics, norm, belief, and habit create a situation in which mutual cooperation is something rational, not competitive. Thus enabling the sustainable usage and management of the common good in a relatively small scale.

The narrative of food commons assumes that food sharing is a material basis for transformation in a capitalist regime and an ideal force to democratic discourse. The narrative is powerful enough to refashion the mode of governance in a risk society. More clearly, the identification of food as an open social construct with fluid boundaries can deprive food of its character as a commodity. Food as a commons adopts the principle of abundant food, that is, food as a renewable resource and sufficiently accessible. Therefore food as commons suppresses the logic of self-centred capitalism that only benefits or gives profit to certain actors and the market. Commons and the models of collective action require a certain level of trust and expectancy, as well as a dependency (hence there is a mutual help—gotong royong) that are spread across all members in the future.

These attributes cannot be assumed to be common amongst all food citizens on the basis of being “eater”, any claim to the commonality that obscure difference and embedded asymmetries between actors is likely to reproduce them. We cannot ignore that the members of the commons coming from asymmetrical power relation. Every individual in the practice of commoning is connected to each other because of the common resource of the social structure formed previously by existing relations of power where there are different divisions of labor and status, starting from class, gender, ethnicity, and age. Examining the issue of asymmetrical relations in the practice of commoning in Yogyakarta, the actors or agents involved in the collective do not come from the same power. While those who donate provide bigger funds than those who volunteer, the volunteers themselves are capable to contribute labour and provide other facilities, such as a kitchen for cooking and transportation to distribute meals. Poor families, daily workers, and handicapped groups who are vulnerable do not come from a more benefited circumstance than those who are aid providers. However, due to the transformative-resistant attitude, they are united in the sense of food commons.

Various loci of resistance against hegemonic narratives emerged in many places: one of them is close to me, having happened in Yogyakarta. Dapoer Bergerak, Sama-sama Makan, and Solidaritas Pangan Jogja have a common thread in the form of food which encourages them to practice commoning when the pandemic repels Yogyakartans. They have taken the chance and overcome obstacles to operate in the niche arena by enabling a transformative food movement. While COVID-19 pandemic was occurring globally, they have reclaimed the narrative of globalisation from below by preserving locality. By this writing, I hope that readers who have experienced the pandemic, not only in Indonesia or Southeast Asia, but around the globe, will notice what these struggles are for. Even though Yogyakarta has now entered the “new normal” period and the aid distribution has been completed, the consciousness that food is a basic human right and of the food commoning practice does not stop here. This is the embodiment of agency in food transitions, as the global food system begins to shift to a more sustainable dimension. Niche transformation and globalisation from below having root in the locality will gradually develop through a learning process, and the expansion of social networks and supporting the intent of the process rather than the end can help to question, break down, and destabilise the capitalistic mode of foodways. It can also help to bring a mode of production which is not formed by exploitation and adequately dealing with risks in modern society.

References

Euler, J. & Gauditz, L., 2017. degrowth.info. [Online]. Available at: https://www.degrowth.info/en/2017/02/commoning-a-different-way-of-living-and-acting-together/. [Accessed 22 August 2020].

Fauzia, M., 2020. money.kompas.com. [Online]. Available at: https://money.kompas.com/read/2020/01/15/204900826/kesenjangan-penduduk-tertinggi-terjadi-di-yogyakarta. [Accessed 2 October 2020].

Jarosz, L., 2014. Comparing Food Security and Food Sovereignty Discourses. Dialogues in Human Geography, 4 (2), pp. 212-217.

Pemprov Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, 2020. corona.jogjaprov.go.id. [Online]. Available at: https://corona.jogjaprov.go.id/. [Accessed 2 October 2020].

Swastika, G. L., 2018. Mediatisasi #stopfoodwaste: Studi Kasus pada Garda Pangan. Jurnal Ilmu Komunikasi AKRAB, 3(2), pp. 413-436.

Vivero-Pol, J. L., Ferrando, T., De Schutter, O. & Mattei, U (Eds)., 2019. Routledge Handbook of Food as A Commons. 1st Edition. London and New York: Routledge.

Young, A. M., Eckstein, J. & Donovan, C., 2015. Rhetorics and Foodways. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 12 (2), pp. 198-199.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

* I send my gratitude and kind regards to Dapoer Bergerak, Sama-sama Makan, and Solidaritas Pangan Jogja who helped through the writing process and given me the comprehensive information. I cannot thank enough. I hope we can beat this pandemic.