“ Before the pandemic, over 70 million workers, or more than half of Indonesia’s workforce, earned their livelihoods in the informal sector. Although not all informal workers are poor and not everyone who is poor works in the informal sector, the informal sector in Indonesia is often linked to vulnerable employment and unstable income.”, writes Joanna Octavia, is a Doctoral Candidate at the Warwick Institute for Employment Research.

_______________________________________________

Unregistered, unregulated and unprotected, informal workers in Indonesia have been disproportionately affected by the economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this post, I briefly discuss the current labour regime and working conditions of the country’s informal workers, followed by the relief offered by the government in the wake of the pandemic outbreak. I also consider the main challenges facing the crisis response and propose five short-term and long-term policy recommendations.

An overview of the current labour regime

Currently, state recognition for informal workers in Indonesia is minimal. The governing Law on Manpower and its supporting policies do not recognise informal workers, specifying workers as only those who possess formal working arrangements with and receive income from an employer.

In reality, employment arrangements for various types of work in Indonesia, such as domestic work, are often done informally and verbally without a written contract. These practices, themselves a result of prevailing social norms, often disguise the existence of an employment relationship between the worker and the employer, leaving the worker with little to no legal protection. Benefits of formal employment, such as employer-sponsored insurance, paid time off, advanced notice of dismissal and severance pay, are not applicable to informal workers.

The second type of informal work popular in Indonesia is own-account work, in which workers are self-employed without an employer whom they report to. Examples of such occupations include street vendors, as well as platform-based motorcycle taxi drivers, who in Indonesia are classified as independent contractors by platform companies.

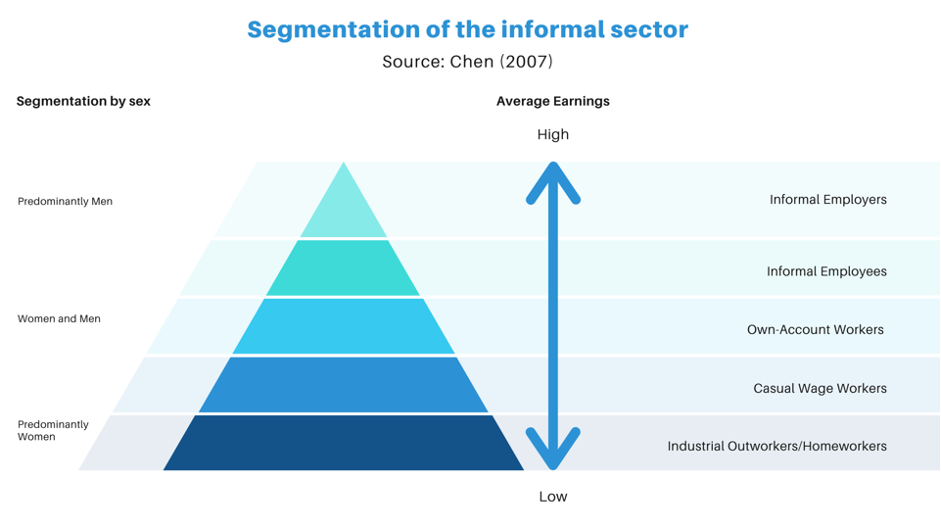

Figure 1: This figure was produced by Chen (2007), and it illustrates the five groups of informal sector workers in the developing world. From Chen, M. (2007). Rethinking the Informal Economy: Linkages with the Formal Economy and the Formal Regulatory Environment. (DESA Working Paper No. 46). Retrieved from United Nations.

In 2015, the Social Security Agency for Worker’s Welfare (BPJS Ketenagakerjaan) launched the non-employee scheme, which informal workers, including self-employed and own-account workers, can sign up and pay for independently. However, uptake on the non-employee scheme has been relatively low: data from the agency indicated that, as of September 2019, only 4 to 5 million informal workers – out of more than 70 million informal workers nationwide – had signed up for the scheme.

Informal sector and COVID-19 response

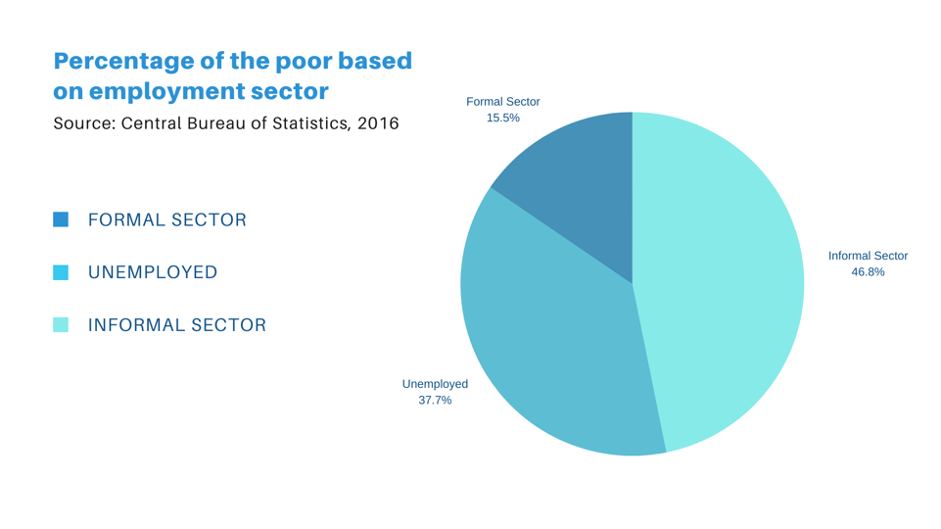

Before the pandemic, over 70 million workers, or more than half of Indonesia’s workforce, earned their livelihoods in the informal sector. Although not all informal workers are poor and not everyone who is poor works in the informal sector, the informal sector in Indonesia is often linked to vulnerable employment and unstable income. A majority of Indonesia’s poor earn their livelihoods in the informal sector or are unemployed (Katadata, 2016).

Figure 2: Percentage of the poor based on employment sector. Central Bureau of Statistics, 2016

The pandemic outbreak in early 2020 and the strict physical distancing and lockdown measures that followed immediately halted daily activities and led to the closure of businesses, schools, and public places in numerous urban centres across Indonesia. As more and more people stayed home, changes in mobility and consumption behaviours created a severe disruption to the earnings of informal workers, such as street vendors and transport drivers, who depend on these activities to sustain their livelihoods. Other informal industries that require in-person connections, including domestic work, were among the hardest-hit. Some, such as casual workers in the tourism industry, were put out of work entirely as businesses continued to decline.

Various reports suggest that average daily earnings of informal workers have fallen by as much as 80 percent since the start of the pandemic, though actual figures vary across different occupations. These losses in income were further increased as massive layoffs pushed people out of the formal sector and into informal work, making the informal labour market more competitive (Interview with a platform-based motorcycle taxi driver, 2020).

Obstacles to government intervention

Due to the heterogeneity of the informal sector, at Rp 2.1 million or US$145.80 per month (Rp 454,652 or US$32 per capita per month), and did not qualify for government support before the pandemic (Asian Development Bank, 2010; Central Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Nonetheless, a few months into the pandemic, the Indonesian government launched an additional range of social assistance programmes to reach t e segment of the population that was previously not covered by any other programme. These included but are not limited to: staple food packages for low-income families in the Greater Jakarta region; a monthly cash transfers (BLT) programme of Rp 600,000 (equivalent to US$42) for underprivileged families across the country; and the pre-employment card program that delivers training funding for job seekers and laid-off workers (Barany, Simanjuntak, Widia and Damuri, 2020; Hirawan, 2020).

The actual effectiveness of these programmes in mitigating the economic impact of the pandemic on informal workers remains unknown. There are several reasons for this:

Informal workers are undocumented, which makes identifying and reaching them challenging. Informal sector workers in Indonesia are spread across sectors and occupations, ranging from street vending to construction, domestic work, various forms of transit, mostly on short-term arrangements. In many cases they earn just a little above the poverty line and thus were considered not “poor enough” for social assistance schemes prior to the pandemic, putting them off the government’s radar. Due to their lack of documentation, little is known about their conditions, making it challenging to know exactly who they are, what they do, and how to reach them.

Challenges in delivery were exacerbated by outdated domicile information. Various studies on the informal sector suggest that a proportion of informal sector workers in urban areas were economic migrants who moved to seek better employment opportunities. Manning and Pratomo (2013), for instance, suggested that recent migrants tended to work in the informal sector, while Fanggidae, Sagala and Ningrum (2016) found that one-fourth of platform-based motorcycle taxi drivers they had surveyed in Jakarta were migrants who were born outside of the capital city. In terms of domicile, more recent research by Wauran (2012) indicated that only 42 percent of urban informal workers owned the house that they were living in, while others typically rented a house or a room in a boarding house.

It is important to note that a consolidated way to report a change of address currently does not exist. As a result, these changes in domicile were not accounted for in the first waves of social assistance outreach efforts, resulting in aid packages not reaching the targeted beneficiaries. For instance, one platform-based motorcycle taxi driver I spoke with told me that since the start of the pandemic in-kind social assistance packages have been delivered to his old address – indicated on his national identity card – and none to his current address.

Reasons, why workers choose to work in the informal sector, may vary. Early theorists believed that workers enter the informal sector while they seek formal employment (Hart 1973; ILO, 1972). However, in recent years, other approaches to informality suggested that workers may choose to stay informal in order to avoid burdensome operational and regulatory costs, including taxation (de Soto, 1989; Maloney, 2004). While this may have been seen as a survival strategy, the pandemic has demonstrated that operating outside the formal reach of the law had left them vulnerable to various risks such as losing their livelihoods, exposing them to greater hardship in reality.

Policy recommendations

Obstacles to government intervention mostly revolve around the needs for better data and – in the longer term – to integrate informal workers into the formal regulatory environment

Implementation of a national database to ensure targeted support. The Single Identity Number project that the Indonesian government is currently consolidating aims to integrate existing identifications, such as driver’s license and family registry, into a single identity that is tied to the national identity card. Having a consolidated ID system and formally registering all individuals in the system will make it much easier to design and deliver support measures to those working in the informal sector.

It is important that the government stays sensitive and responsive to the concerns of informal workers – many of whom have previously chosen to stay unregistered – when developing a national database that could track not only their identity but also their economic activity. For example, although informal workers did not pay income tax in the same way as their formal counterparts, in reality they have often been indirectly taxed through various costs such as bribes and rental fees for market stalls (Rothenberg, Gaduh, Burger, Chazali, Tjandraningsih, Radikun, Sutera and Weilant, 2016). Mechanisms such as income thresholds and progressive taxation rates, efforts to avoid data misuse, as well as a sweeping evaluation of factors affecting informal working conditions, should be considered alongside the creation of a national database.

Redeployment of workers into new, essential roles. In the short-term, data from the national database can be used to redeploy informal workers into new, essential roles. The Indonesian government had responded to challenges around unemployment by launching cash for work scheme to build infrastructure such as roads and buildings. Nonetheless, more can still be done on this front, in particular in urban centres, for example in Jakarta and Surabaya.

To achieve this, the government could explore partnering with organisations and community initiatives serving the interests of the informal sector, such as the Urban Poor Consortium and RekomenJasa, to map out informal workers’ skills and qualifications, and matching them with market demand. While it is true that many industries have been disrupted, others, such as medical services, ecommerce and logistics, are growing as a result of changing consumer sentiment and behaviour. There are opportunities to reskill and upskill workers to take advantage of this growth.

Revision of the Law on Manpower to recognise informal workers and account for all types of work. The ease with which informal workers could lose access to their only source of income and be terminated without prior notice during this pandemic has underscored the importance of ensuring that the Law on Manpower is extended to all workers. Segmenting the different types of informal workers by their working arrangement or employment model will aid policymakers in evaluating the factors affecting informal workers’ jobs, their urgent basic needs, and the safety nets that they are using. Furthermore, an increased understanding of the sector can help policymakers to better understand the needs of informal workers, clarify the obligations that each stakeholder has towards a particular worker through policy change and fine-tune future assistance as necessary.

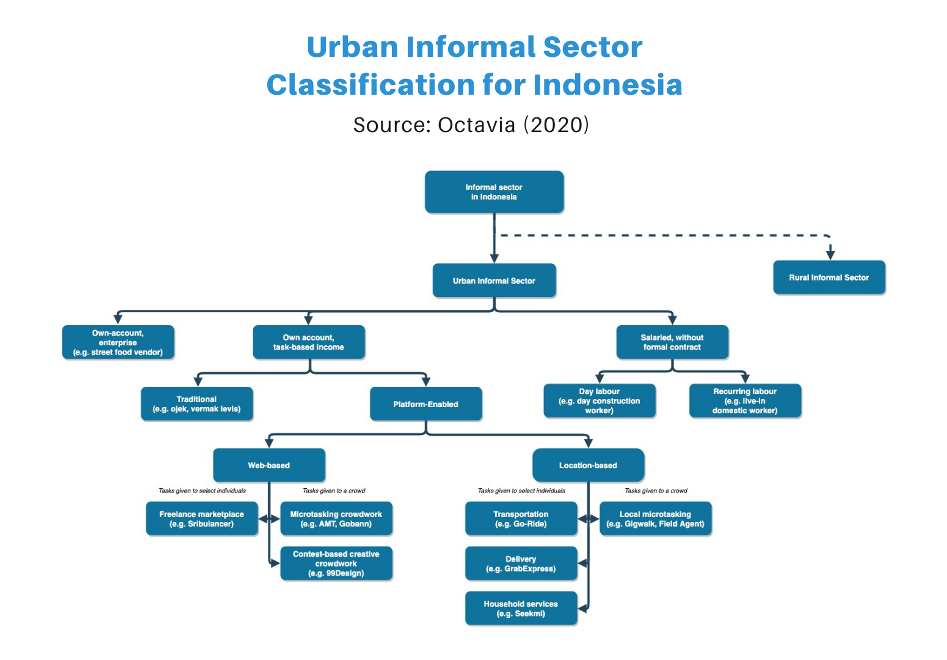

Figure 3: The platform-based classification is adapted from Lettieri et al. (2019). Platform Economy and Techno-Regulation – Experimenting with Reputation and Nudge. Future Internet, 11(7), 163.

Creation of supporting regulations to account for platform-based work. Platform-based work has gained popularity in recent years with increasing access to affordable smartphones and internet packages. To illustrate, there are approximately 4 million platform-based motorcycle taxi drivers, over 5 million freelancers and 5 million fintech agents facilitating digital financial services across Indonesia. Due to their low barriers to entry, platforms have been instrumental in absorbing labour and alleviating unemployment in urban areas.

Around the world, platforms face mounting criticisms over their algorithmic management techniques, resulting in low pay, overwork, and exhaustion (Wood, Graham and Lehdonvirta, 2018). Employment relationships between platforms and the workers delivering the orders coming through the system, who in most cases are classified as independent contractors rather than employees, have been the subject of lawsuits in many countries. However, it is important to note that informal work is experienced in distinct ways across platforms, as each platform is designed and operates differently (Octavia, 2020).

In Indonesia, the relationship between platforms and workers are not yet regulated. Like in many countries, the relationship, along with the rights and obligations each party holds, are simply outlined by a digital contract agreed to by workers when they register on a particular platform. In most cases, workers are not able to negotiate service fees nor working conditions, which creates imbalances of power when platforms make decisions. Given the popularity and pervasiveness of platform work, it is imperative for the government to design supporting policies that protect workers while at the same time providing business certainty to customers and respecting the flexibility that some platforms enable.

Rethinking social protection to offer a safety net for all. Lastly, the pandemic has highlighted the fragility of informal working conditions and revealed the insufficient coverage of social protection for informal sector workers. The low uptake of the non-employee scheme suggests various possibilities: that information may not have reached the targeted workers, that both the operational and regulatory costs outweigh the benefits of receiving protection, or that there is not a great enough incentive to be registered. This highlights a need for the government to consider basic social safety net provisions that are expansive, inclusive and can reach people who are at risk in quick and efficient ways.

Portable benefits that are attached to the individual, instead of the work that they do, could be explored as a better alternative to the current social protection scheme that differentiates between employees and non-employees. This is especially applicable for workers who are employed by multiple employers, or who receive work through an agency or platform on a per-piece basis. Instead of workers having to pay into the non-employee insurance scheme independently, employers or stakeholders who benefit directly or indirectly from the labour of the worker could pay an amount, or an incremental percentage of the workers’ earnings to his or her portable benefits account. Workers could then use these funds to pay for their insurance or other services, such as retirement savings.

Conclusion

Informality has been a part of the Indonesian labour market, and excluded from the formal regulatory environment, for a very long time. The pandemic has been especially devastating for Indonesia’s 70 million informal workers who continue to earn their living without a safety net. Without intervention, the severe economic costs of the COVID-19 crisis will push millions of informal workers into poverty.

As the economy moves towards recovery, it is imperative that we support policies as well as a regulatory environment that is inclusive and responsive to the needs of all workers regardless of their working arrangements and employment relationships. The policy challenge is in recognising the size and significance of the informal sector and acknowledging the transitions of workers across sectors and geographies in the changing world of work.

References

Asian Development Bank. (2010). The Informal Sector and Informal Employment in Indonesia (Country Report 2010). Asian Development Bank, BPS-Statistics Indonesia. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28438/informal-sector-indonesia.pdf

Barany, L. J., Simanjuntak, I., Widia, D. A., & Damuri, Y. R. (2020). Bantuan Sosial Ekonomi di Tengah Pandemi COVID-19: Sudahkah Menjaring Sesuai Sasaran? (CSIS Commentaries ECON-002-ID). Retrieved from https://www.csis.or.id/publications/bantuan-sosial-ekonomi-di-tengah-pandemi-covid-19-sudahkah-menjaring-sesuai-sasaran

Central Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Persentase Penduduk Miskin Maret 2020 naik menjadi 9,78 persen [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.bps.go.id/pressrelease/2020/07/15/1744/persentase-penduduk-miskin-maret-2020-naik-menjadi-9-78-persen.html

Chen, M. (2007). Rethinking the Informal Economy: Linkages with the Formal Economy and the Formal Regulatory Environment. (DESA Working Paper No. 46). Retrieved from United Nations.

De Soto, H. (1989). The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution of the Third World. New York: Basic Books.

Fanggidae, V., Sagala, M. P., & Ningrum, D. R. (2016). On-Demand Transport Workers in Indonesia: Towards understanding the sharing economy in emerging markets. Perkumpulan Prakarsa. https://www.justjobsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/toward-understanding-sharing-economy.pdf

Finansialku. Rincian Iuran BPJS Ketenagakerjaan Yang Harus Anda Bayar (2020). Retrieved from https://www.finansialku.com/iuran-bpjs-ketenagakerjaan/

Hart, K. (1973). Informal Income Opportunities and Urban Employment in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11(1), 61-89.

Hirawan, F. (2020). Optimising the Distribution of the Social Assistance Program during the COVID-19 Pandemic (CSIS Commentaries ECON-003-EN). Retrieved from https://www.csis.or.id/publications/optimizing-the-distribution-of-the-social-assistance-program-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

International Labour Office. (1972). Employment, Incomes and Equality: A Strategy for Increasing Productive Employment in Kenya. ILO. https://www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/1972/72B09_608_engl.pdf

Katadata. (2016). 37 Persen Penduduk Miskin Tidak Memiliki Pekerjaan. [Data file]. Retrieved from https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2016/11/08/37-persen-penduduk-miskin-tidak-memiliki-pekerjaan

Lettieri et al. (2019). Platform Economy and Techno-Regulation – Experimenting with Reputation and Nudge. Future Internet, 11(7), 163.

Maloney, W. F. (2004). Informality Revisited. World Development, 32(7), 1159-1178.

Manning, C., & Pratomo, D. (2013). Do migrants get stuck in the informal sector? Findings from a household survey in four Indonesian cities. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 49(2), 167-192.

Octavia, J. (2020). Towards a national database of workers in the informal sector: COVID-19 pandemic response and future recommendations (CSIS Commentaries DMRU-070-EN). Retrieved from https://csis.or.id/publications/towards-a-national-database-of-workers-in-the-informal-sector-covid-19-pandemic-response-and-future-recommendations/

Rothenberg, A. D., Gaduh, A., Burger, N. E., Chazali, C., Tjandraningsih, I., Radikun, R., Sutera, C., & Weilant, S. (2016). Rethinking Indonesia’s Informal Sector. World Development, 80, 96-113.

Wauran, P. C. (2012). Strategi Pemberdayaan Sektor Informal Perkotaan di Kota Manado. Jurnal Pembangunan Ekonomi dan Keuangan, 7(3).

WIEGO. (2020). Social Protection for Informal Workers. https://www.wiego.org/social-protection-informal-workers

Wood, A., Graham, M., Lehdonvirta, V., & Hjorth, I. (2018). Good Gig, Bad Gig: Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy. Work, Employment and Society, 0(0), 1-20.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

* As part of her PhD, the author conducted a 9-month fieldwork in Jakarta, Indonesia, interviewing, platform-based motorcycle taxi drivers on their participation in community organising and large-scale street mobilisation. Some of the insights reported in this post are drawn from the data she collected in the field

* Parts of the recommendations outlined in this post are based in a policy commentary the author previously published with the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, “Towards a national database of workers in the informal sector: COVID-19 pandemic response and future recommendation”.

Very excited to read about your research. Have just completed PhD at SOAS on Indonesia’s domestic worker movement and would love to meet and chat with you. Am now doing book based on PhD as an independent scholar. Would love to meet up

Do get in touch if youd like to \

Sincerely

mary Austin