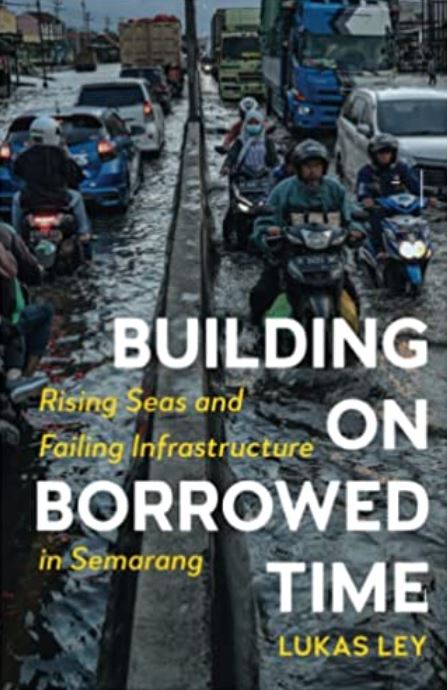

In his first monographic publication, Building on Borrowed Time: Rising Seas and Failing Infrastructure in Semarang, Lukas Ley eloquently describes the kampung Kemijen at Semarang that always faces flood, writes Adrian Perkasa

_______________________________________________

There are plenty of works on Indonesian kampung (neighbourhood); however, only a few discuss a kampung where disaster is chronic. In his first monographic publication, Building on Borrowed Time: Rising Seas and Failing Infrastructure in Semarang, Lukas Ley eloquently describes the kampung Kemijen at Semarang that always faces floods, particularly rob. Rob is a local Javanese language for tidal flooding or tidewater. Tidal flooding has been a threat to Java’s northern shore, particularly in Semarang. It occurs on a constant basis, and the intensity worsens year after year.

Perhaps the reader of this book expects a gloomy or murky illustration of the kampung. On the contrary, Ley offers the sense of the local residents’ buoyancy facing the rob. He employs a ‘sinking-in’ observation as a method to study ‘the permutations of the river, infrastructural shifts, and the social experience of flooding’ (27) in Kemijen. As he presents in his book, only the last part contains frustration feelings and disappointment of the residents, or at least his main interlocutors.

Ley’s study has five chapters, excluding the introduction and afterword. By using historical documents, colonial maps, secondary literature references, and several colonial maps, he writes a kind of historiography of the northern wetlands area of Semarang city from the colonial period to the more recent time. In the second chapter, Ley attempts to comprehend the influence of political transition and evolving urban ecology on the development of poor neighbourhoods in Semarang’s north via water governance.

In the subsequent chapter, he captures the everyday life look and feels like in the Northern part of Semarang nowadays. This part has the most pictures compared to other chapters because it contains a photo-ethnographic tour. Chapter 4 analyses how government-sponsored citizen participation initiatives change local behaviour and how actions of organizing bottom-up responses to rob affect social order in the kampung. The last chapter with the title ‘Promise’ shows how the initial optimism of the new polder project at Kemijen, which required local residents’ active participation, slowly faded into disillusionment.

According to Ley, living in the marshy North Semarang has exposed residents to several dangers, including illness outbreaks and periodic floods, since at least the early twentieth century.

Due to the government’s stigmatization, danger began to develop from inside the kampung over time. Furthermore, danger emanates from the city’s defective infrastructure, which was intended to cure it of its imagined gloomy features. Instead of the government providing a solution, communities and people must organize their own resources in order to respond to an unequally distributed danger, particularly rob.

The latest solution by the government discussed in this book was the Semarang Polder Project. Designed by a consortium of Dutch and Indonesian experts, this project was imagined as the beginning of a new era of urban water management in Indonesia. A polder system, in short, is a hydrologically closed system consisting of dikes, dams, and water pumps. Following the Netherlands’ polder system, the polder in Indonesia also created a requirement for the public, especially local residents, involvement. Indeed, the Semarang’s polder in the Banger area established a special water authority called SIMA in 2010. In this authority, local residents and academics were able to play an important role. Unfortunately, this idea is facing failure and only reproducing a cultural imaginary of North Semarang since the Dutch colonial period.

The colonial period according to Ley, is a source of the marginality of the Northern area in Semarang urban development discourses. He argues that colonial urban planning placed the swamp ‘particularly low in the hierarchy of liveable places, was strongly associated with a degraded human needing (hygienic) discipline’ (51).

Consequently, the colonial government saw urban kampung and its residents as a source of danger, backward, and lagging behind the trend of human evolution. Two chapters at the book’s beginning elucidate how the colonial power’s spatial hierarchy still has a big influence over contemporary images and ideas of kampung Kemijen and its people. Ley also brings the case of normalisasi sungai (river normalization) during the 1980s as the epitome of that colonial view.

Looking at another policy of the Indonesian regime during that era, namely Normalisasi Kehidupan Kampus (Normalization of Campus Life), Ley argues that river normalization ‘intended to deter people from settling along rivers that were thought to constitute a realm in which subversive subjects lived and flourished’ (70). The government often condemned the people who settled illegally on the riverbank as a primary cause of floods. Moreover, he draws a linkage between the river normalization in the 1980s with state modernization and interventions in the colonial period. Even he writes, ‘river normalization, a colonial vehicle of modernization, never actually ended’ (88).

On this point, this fascinating book may lend itself to criticism. In fact, there was no river normalization project at all in Semarang during the colonial period. Actually, in chapter 2, Ley also describes how the Indonesian government only initiated river normalization in 1985. By making a kind of a longue-durée linkage to the colonial past, Ley easily got trapped into what Frederick Cooper (2005) called looking at history ahistorically, especially by performing leapfrogging legacies. In short, the authors who follow this mode of writing tend to claim that something at time A caused something in time C without considering time B, which lies in between. In this book, Ley says almost nothing about the period after decolonization and just makes a claim that what happened with the river-related projects is the continuation of the modernization projects in the colonial period. Perhaps Ley did not have any opportunity to engage with several historiographical works in Indonesian that deal with Semarang in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

Furthermore, another shortcoming of this book is many Indonesian words or terms translation errors. Although it is not only intended for Indonesian but general readers who understand Indonesian will be disturbed by this issue. For instance, kota bawa (18) means city-bring and is not a translation of the low-lying part of Semarang. It should be kota bawah. Pegal (68) means painful or sore. Perhaps what the author means is begal or robber. Neither Indonesian nor Javanese word guyung (77) means united. Maybe what he means is guyub. Digemas budaya (141) literally means excited about culture. Perhaps what he means is dikemas budaya. Another puzzling term is heran saya budaya (182), which I failed to find the proper intention of what the author means.

All in all, the book is worth reading not only for urban studies scholars but also for general readers who want to explore the complexity of living in a chronic disaster area not from the state but the neighbourhood’s perspective.

______________________________________________

* Banner photo front cover of Building on Borrowed Time: Rising Seas and Failing Infrastructure in Semarang, Lukas Ley.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the author alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.