Why do Indonesian retired officers remain politically active after the end of authoritarian rule? Drawing from the INDOMAG (Indonesian Military Academy Graduates) dataset we find that politicised retired officers clustered around military academy classes of the 1970s. These retirees were more professionally skilled officers than their predecessors and also left the armed forces at a time when their post-retirement careers were in disarray as the New Order ended. These push-pull factors were permissive conditions that allowed these retirees to transfer their “professional” skills into the newly democratic political sphere, write Evan A. Laksmana and Terence Lee

_______________________________________________

For most of Indonesia’s history, the military has been deeply involved in political life. The end of Suharto’s New Order regime ended the TNI’s formal role in politics. And yet, retired military officers remain in the forefront of Indonesian politics.

Consider Indonesia’s presidential tickets since 2004, all of which had a former military general – Agum Gumelar, Prabowo Subianto, Wiranto, and Susilo Bambang Yudoyono. At the local level, retired officers have also run for political office, though few have been successful. Indonesian political parties are led and have recruited these retirees; most have joined Gerindra, Partai Demokrat, and Hanura.

Why do these retired officers continue to be politically active after the end of authoritarian rule?

First, the politically active retired officers are not random nor are they small in numbers. Most of the hundreds of politically active officers are by-and-large from a particular cohort—the professionally skilled officers who graduated from the academy in the 1970s. As group, they are different than their predecessors—those who rose and ruled at the peak of the New Order—and their successors—those who earned their stripes as authoritarian rule was heavily challenged. We contend that the classes of the 1970s is distinctly political.

Second, the rise of the 1970s cohort in post-authoritarian Indonesia can be seen as function of push and pull factors. On the one hand, the class of the 1970s were among the most professionally trained and operationally tested group of officers tasked with defending the regime and ruling the country. The military’s under-developed personnel management likely pushed their post-retirement careers into disarray as the New Order ended. On the other hand, the post-1998 democratic space, devoid of strong political parties, created a vacuum filled by these men seeking to transfer their “professional” skills into the political sphere.

Who are the Politically Active Retirees?

We substantiate our argument using an original hand-coded Indonesian Military Academy Graduates (INDOMAG) dataset. From a master list of 20,646 military officers, we collected biographical and command information of 2,793 retired Army officers, commissioned from the 1940s to the 1980s. The dataset comprises personal (religion, ethnicity, and birthdate), professional (education, training, command, and combat experience) and post-retirement (exit rank, political and non-political activities) variables.

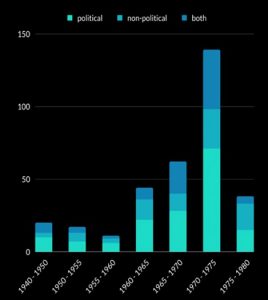

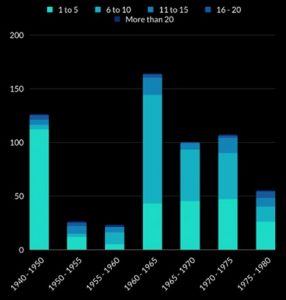

Our dataset reveals that the academy classes 1970 to 1975 in particular were the most “political” group compared to the previous and preceding cohorts (Figure 1). Prominent military officers from the 1970 to 1975 cohorts include Prabowo Subianto, Susilo Bambang Yudoyono, and Luhut Pandjaitan.

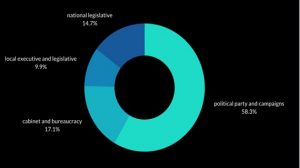

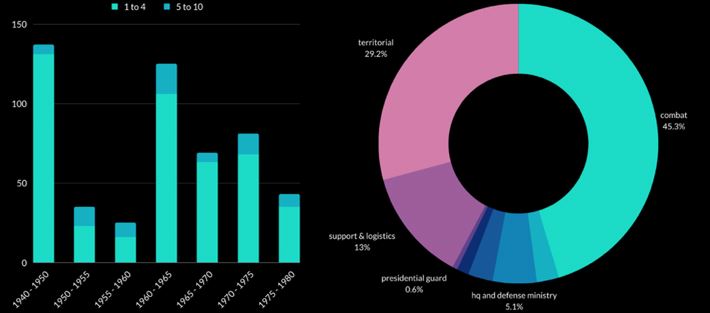

Most of the political activities were partisan politics—military retirees joined or led political parties or were part of political campaigns. The next two largest groups of politically active retirees were found in the national legislature (DPR) followed by the state bureaucracy including cabinet ministers (Figure 2).

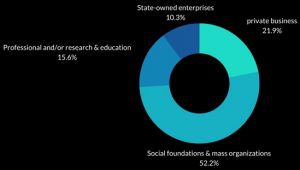

Most of those who chose not to be involved in direct partisan politics were involved in social foundations and mass organisations (e.g., NU, Muhammadiyah, national sports associations) with underlying political potential (see Figure 3 below). One could also argue that retired officers who entered major private business groups and SOEs continue to build on and deploy the political network developed during their military service.

“New Professionalism” and Political Entitlement

Under the New Order, the military academy classes of the 1970s saw the largest enrolments. At that time, expanding the number of entrants to the academy was necessary to replace the retiring revolutionary-era officers while ensuring a steady stream of “professional” officers to defend, control, and manage the regime across an expansive array of challenges, from political, social, economic, to security affairs.

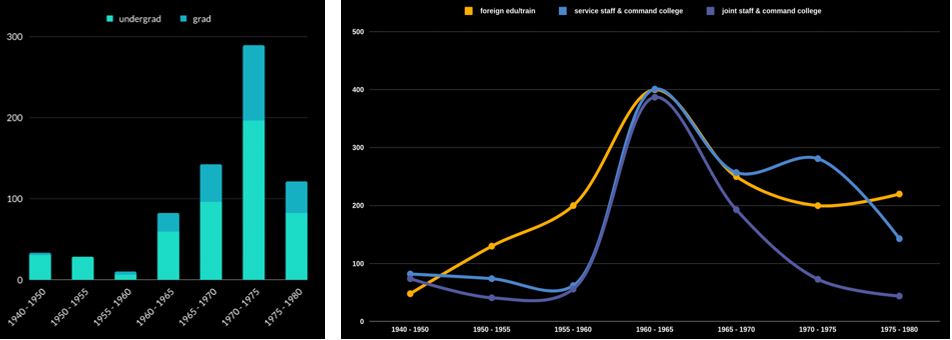

The 1970-1975 cohorts were particularly among the best educated; more than a third held undergraduate degrees and more than 10% held graduate degrees. Figure 4 also shows that foreign and domestic professional military education (especially staff and command colleges) grew in importance for these officers as they seek to become more professional.

The 1970s cohort were also the third most decorated group after their revolutionary predecessors (Figure 5). Most of these officers had participated in domestic security and counter-insurgency operations (e.g. Irian Jaya, East Timor), reflecting the rise of a “new professionalism” in the armed forces. Coined by Alfred Stepan in 1973 to describe the military’s expansion into the political realm in Brazil and Peru, new professionalism describes the importance of political managerialism as the officer corps participates in governance and internal security.

Further examination of the career patterns supports this hypothesis. Almost three quarters of the retired officers in the INDOMAG dataset had served in combat ready (Kopassus and Kostrad) and territorial (Kodam, Korem, Kodim, Koramil) postings, and many of them, especially class of the 1970s, saw combat campaigns, especially in East Timor (see figure 6).

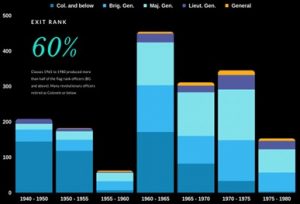

The 1970s cohort of military officers thus represents the pinnacle of the “new professionals”—highly educated, combat-tested, decorated, and politically-skilful in defending the New Order regime and governing the country. Unsurprisingly therefore, many of them retired as flag-rank officers (brigadier generals and above) as Figure 7 shows.

However, the under-institutionalised, personalistic and authoritarian military personnel management system led to two important concomitant trends. First, only the politically savvy professional officers—especially Suharto loyalists—made it to the top of the New Order during the 1990s. Many professional members of the class of 1970s had the skills and education to run the country but felt their political break never came when Suharto resigned. It is conceivable officers would seek post-retirement opportunities and political relevance befitting their senior rank but diminished by the lack of important military command positions while in active service.

Second, the absence of sufficiently ‘strategic’ and prestigious command billets after 1998 for larger numbers of the 1970s graduates meant that their post-retirement careers would have to be built around their added value—their expertise in political managerialism. This is particularly so since senior officers anticipate courtesies and seek influence well into retirement. By the late 1990s, the 1970s graduates had become generals, and expected that their broader national role would continue. This entitlement stems primarily from the academy prestige and the expertise gained from years of professional and combat operations.

Taken together, these two trends created a pooled group of military retirees with the skills, propensity, and group self-entitlement to play active political roles—the 1970s “new professionals” of the officer corps.

The Opening Democratic Space

The opening of democratic space allowed greater opportunities for these retired officers to enter partisan politics. During the New Order, retired officers need not actively compete for post-retirement perquisites. The kekaryaan (civilian secondment) system and its related deployments of active and retired military personnel to socio-economic-political positions in government and society were amply provided for.

However, following the end of the Suharto regime, the military lost much of their political influence and had to disengage from practical day-to-day politics. Active military officers could not easily hold civilian positions in the bureaucracy, and the armed forces was no longer represented in the national parliament and local legislatures. The military’s political withdrawal led to a sense of uncertainty and concern within an officer corps that had taken for granted high-profile political careers as part of its guaranteed professional benefits.

The reformasi period brought about an opening in the democratic space with the proliferation of political parties and electoral contestation. New opportunities in partisan politics then emerged for politically savvy and well-trained retired officers seeking to remain relevant in the national arena. Parlaying ties developed over their careers within the military, leaders like Prabowo Subianto and Susilo Bambang Yudoyono recruited fellow officers to assist their political endeavours.

Implications for the Future

Is the trend of politicised retired officers likely to continue once the 1970s generation have passed from the scene? We contend yes for the following reasons.

First, the TNI’s personnel management system remains broken. There are more officers than there are available and commensurable billets. The 2004 extension of the mandatory retirement age from 55 to 58 has worsened the logjam—leaving hundreds of colonels on hold for a few years for their next jobs. Rather than overhauling the military’s personnel management system, Indonesia’s political and military leaders instead kicked the can down the road by expanding existing TNI units and structures and “upgrading” dozens of key command positions. They also relied on horizontal rotations, where officers were moved within the same rank or positions were rotated among officers from the same Academy class.

While there seems to be a temporary reprieve in the internal promotion pressures for now, there is a growing perception among officers over the past decade that political network remains necessary to secure high-level promotions and positions. In other words, with an under-developed personnel management system, the potential politicisation of command positions remains. This potential grows when we consider that these officers still look up to their seniors from the class of 1970s that proliferate among major political parties.

Second, the proliferation of politically active retired officers has led to a pathway that the academy graduates of the 1980s could emulate. We have seen how two former TNI commanders, Moeldoko (class of 1981) and Gatot Nurmantyo (class of 1982), have parlayed their military influence into political ambitions. Moeldoko currently serves as President Widodo’s chief of staff and was behind a clumsy bid to take over the Democrat Party (PD) in 2021. Gatot Nurmantyo has been a strident critic of the current Indonesian president since leaving the military and is well-known for harbouring major political ambitions.

Finally, Indonesia’s political party system remains weakly institutionalised and receptive to retired military officers with political ambitions. Increasing in salience are partai milik pribadi or ‘privately owned parties,’ created to serve as political vehicles for private individuals or oligarchs. Examples are the National Democrat Party (Nasdem) founded by Metro Group media tycoon Surya Paloh, and Hary Tanoesoedibjo’s Indonesian Unity Party (Partai Perindo). Established major parties like Golkar and PDI-P also boasts retired officers in their leadership boards, ministers, and parliamentarians, while parties created by retired generals like Democrat Party and Gerindra continue to recruit retirees into their rank.

While these trends remain, it would be difficult to expect retired military officers to simply fade away in Indonesia’s democratic journey ahead, for better or for worse.

______________________________________________

*Banner photo by AWG97 on Wikimedia

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

*Evan A. Laksmana and Terence Lee presented this work at a Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre Seminar on Wednesday 15 June 2022. Further information including a link to the video recording can be found here.