Regions are not stable historical phenomena. They are, to draw upon a metaphor from Southeast Asian Studies, expanding and contracting mandalas. The alteration is not fundamentally their geographical scope but their social significance; it is their very existence that waxes and wanes, writes Joseph Scalice

_______________________________________________

To come to Southeast Asia from the Philippines is to come at it sideways. The fraught question that has occasionally occupied scholars over the last half-century – does the region even exist? – is compounded by the awareness that if, in fact, it does, you are a second-class citizen. The first edition of D.G.E. Hall’s tome on the region excluded the country, and when Filipinists give a job talk, the search committee inevitably invites the Latin Americanists. The eastern littoral of Asia’s Mediterranean often falls off the map. Every decolonised nation shares a community – marked by both legacy and injustice – with its former metropole, but few are as thrust back by scholarship within the ambit of their former colonial ruler as the Philippines. This sense of begrudging and partial inclusion imbues the Southeast Asian region for Philippine scholars with a sense of integrated solidity, of concreteness, that is largely lacking from other vantage points. The Philippines resides in multiple non-overlapping imagined communities: the vast diaspora, the metropoles of Spain and the United States – hazily understood but palpably contemporaneous, the Old and the New Testaments of empire – and, and this is a point of pride, Southeast Asia. The existence of the region is profoundly entangled with national imagining.

Reservations over the existence of region often stem from the historical awareness that, within both scholarship and geopolitics, they were inescapably creations of the Cold War, the chunking of the world into manageable units of a less visible empire. These are salutary concerns. The rush to embrace them, however, expressed more than mere political circumspection. It must be acknowledged that these reservations shield us from the enormity of the scholarly task that confronts us. We in the humanities, in particular, are notoriously solitary souls (at least during office hours), and the intrinsic complexity of the region – among the most linguistically, culturally, and historically diverse in the world – requires of us a vast collective endeavour.

To an extent, like the imagined community of nation, when region becomes a durable historical category, it becomes modular. It is the subject of both imposition and importation. SEATO, the even more oddly named NEATO, and ASEAN were political forms that structured a region in service to particular interests. They were also, however, forms of self-imagining. The decolonising region adapted, constituting itself through imposed forms.

That certain social layers perform region through these bureaucratic apparatuses and their summits is undeniable, but it remains incorporeal, a shadow theatre imagining. What is lacking are the great masses of the population; without them, region exists but as ritual. The sinews and fibres of the early modern region drew taut with trade and trafficking. While this history informs the region’s modern shape, the postcolonial era is not an atavistic re-emergence.

In the few instances when we find a grassroots imagining of region in the modern period, it remains solitary, even Whitmanic, contained, for example, in the ‘I’ of Minangkabau men on the rantau, like Tan Malaka. The solitary scholar finds their solitary counterpart.

How, then, should we proceed?

At certain historical junctures, dynamic social developments imbue a particular regional form with objective existence. This occurs prior to all of the various imperialist and nationalist imaginings. The contest to constrain the region within rival imaginings has a historical and historiographical significance, and these imaginings take political form and can shape the objective development of the region. They are, however, ultimately derivative. A counter-hegemonic scholarly understanding of region must look beneath all of the imaginings and counter-imaginings to the underlying social changes which impart an objective shape and thrust to the region’s development and upon which the articulated visions of region are imposed.

Regions are not stable historical phenomena. They are, to draw upon a metaphor from Southeast Asian Studies, expanding and contracting mandalas. The alteration is not fundamentally their geographical scope but their social significance; it is their very existence that waxes and wanes. The focal point around which region emerges and disappears is thus also not fundamentally geographical but social and political. Each expansion and contraction construct the region in a somewhat different way.

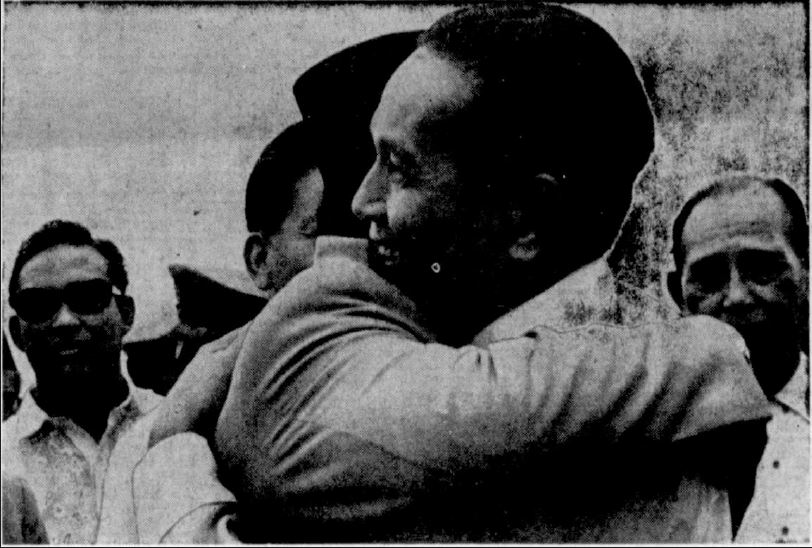

On 14 February 1972, Suharto visited Manila and met with Ferdinand Marcos and advised him on how best to impose dictatorship on the Philippines, instructions which Marcos implemented carefully over the next seven months. The underlying tensions of social unrest and, in response, the transition to authoritarianism as the preferred form of bourgeois rule took on a regional expression. It was, however, more widespread and was not sharply demarcated. The elite opponents of Marcos travelled to Chile, where they met with Allende to discuss how they might stabilise political rule through an alliance with the Communist Party. History, however, tragically moved from Marcos to Pinochet. The mandala of regional authoritarianisms embraced the entirety of the Global South and much of the core as well. It rose upon the Nixon doctrine, mass opposition to America’s war in Vietnam, and explosive social unrest over skyrocketing prices.

Let us look at a much more sharply demarcated example of the social emergence of region upon which various imaginings were imposed.

A decade earlier, the social tensions underlying and fuelling the complex process of decolonisation gave the region of island Southeast Asia an almost unprecedented and profoundly interconnected dynamism. The archipelagic and semi-archipelagic states all sought to achieve national stability, to contain domestic unrest, by redrawing the region. Konfrontasi, the conflict between Indonesia and Malaysia in the early 1960s, was fundamentally a dispute between all of the formative nations in the region over rival strategies for containing the threat of communism by the redrawing of borders. I argue in a forthcoming article in Modern Asian Studies that it was racialised anti-Communism, targeting the Malayan and Singaporean Chinese working populations, that fuelled all of the tensions of this time and gave the region its shape. Lee Kuan Yew sought integration with Malaysia as a means of defeating Barisan Socialis. Tunku Abdul Rahman sought the incorporation of the Bornean territories to prevent Chinese dominance in the newly formed Malaysia. Macapagal sought to secure North Borneo as a barrier against the perceived threat of the Singaporean Chinese. A.M. Azahari sought to create an integrated Bornean federation as a political unit of Malaysia as his own power base and a barrier against the Chinese. Sukarno saw in opposition to Malaysia the ability to retain hold over both the military and the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI), the Indonesian Communist Party. The Indonesian military saw in Malaysia the encroachment of the Chinese, while the PKI denounced it as the approach of British colonialism. All of the racialised fears, which fuelled the contested redrawing of the region, arose upon a social base: the shared drive in the ruling classes to contain working-class unrest in the process of decolonisation, a concern that centred upon Singapore.

The social unrest itself took regional political form, in particular through the intimate connections between the PKI and the newly re-emergent Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP). The PKI sent a representative to Manila named Bakri Ilyas, who oversaw the rebirth of the Philippine party after several years of dormancy. Bakri was responsible for recruiting Jose Ma. Sison, who had a long future career as the founder and head of the country’s Maoist party. The PKP was instrumental in bringing Macapagal, long associated with US interests, temporarily into the camp of Sukarno and the Newly Emerging Forces. In 1963 they merged the largest labour party in the country’s history with Macapagal’s ruling Liberal Party in support of Macapagal’s opposition to Malaysia.

Much of the scholarship produced in this period reflected an awareness of the reality of region, of the mandala at its most expansive. One has a sense from the writings of Kahin, Anderson, and McVey, for example, that what they are examining is part of a larger, dynamically integrated whole. In the wake of 1965 – the crushing of the PKI, the rise of Suharto, the removal of Singapore from Malaysia, and the deployment of hundreds of thousands of American troops to Vietnam – the dynamic region balkanised and became stable. The mandala waned. The first major work on Southeast Asia written by scholars who were mostly graduate students during this period of balkanisation – Chandler, Smail, Wyatt and company – was In Search of Southeast Asia (1971). It expressed a salutary concern, even suspicion, of the existence of the region it investigated. This expressed not simply a heightened awareness of Cold War politics but also manifested the social developments within the region itself.

It was social changes that brought region to prominence and subsequently diminished its significance. Rival imaginings of region rested atop and sought to direct these changes. Our scholarship, and our views on the existence or non-existence of region, were profoundly influenced by this regional process.

______________________________________________

*Banner photo by Manila Times, 7 Aug 1963

*Joseph Scalice was Visiting Fellow at the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre from 15 November 2021 – 30 April 2022. Dr Scalice’s research at SEAC focused on how the Sino-Soviet split impacted critical political developments in the Southeast Asian region.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.