Karl Polanyi warned in 1944 that allowing the market to be the most dominant actor in a society would lead to the downfall of both humans and the natural world. This warning still resonates today. It carried weight during the mass disruption that the financial crisis in 2008 caused, and the climate crisis shows the damage to the natural world that a market-driven and profit-focused society can do. Now again, the coronavirus crisis pits the market on one side and human welfare and the natural world on the other. Yet, the coronavirus crisis also sharpens Polanyi’s warning. It offers the opportunity to put human well-being and the natural world, not the market, at the fore as we return to normal life.

Precarious workers are among the group that the coronavirus crisis hit hardest. The UK prides itself on having a particularly unregulated labour market — which, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, facilitated an explosion of precarious work in the form of temporary work, agency work, unpaid internships, zero-hour contracts, self-employment and involuntary part-time work. Such insecure working contracts allowed corporations to take fewer risks in a more competitive and difficult post-crisis environment. Yet, such flexible working arrangements weaken workers’ rights and security.

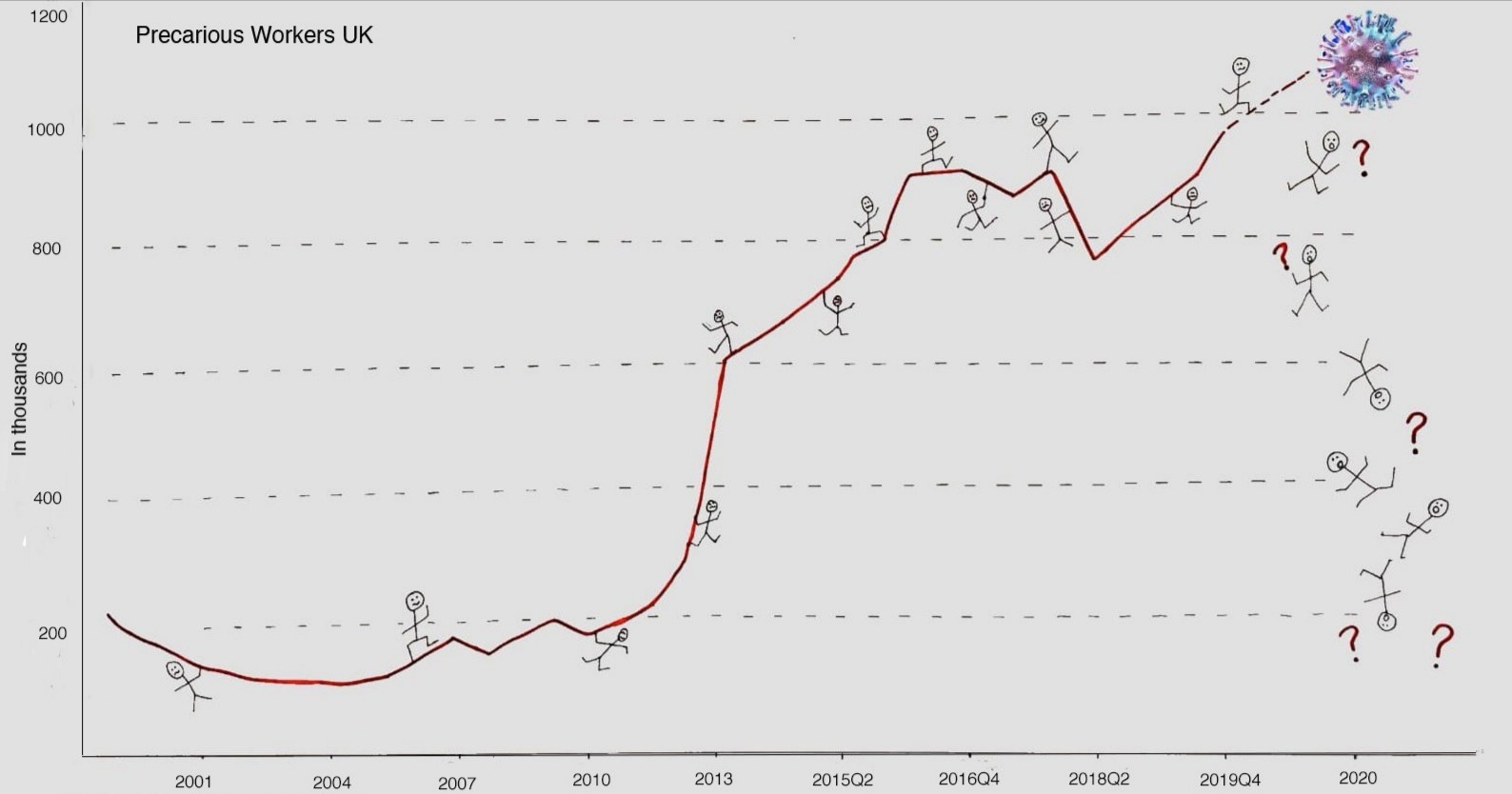

Illustration based on graph of the number of workers, in thousands, who report being in a zero-hour contract in Office for National Statistics Labour Force Survey 2019.

Illustration based on graph of the number of workers, in thousands, who report being in a zero-hour contract in Office for National Statistics Labour Force Survey 2019.

Although the impact of the coronavirus crisis on precarious workers is devastating, it offers us three reasons for optimism: we have an opportunity to strengthen the safety net for all, precarious workers have an opportunity for mobilization and the coronavirus crisis undermines neoliberal ideology.

The coronavirus crisis invites concerns about welfare of precarious workers, many of whom qualify as key workers. Official National Statistics data show that women who are domestic workers, work in the caring, leisure and other service occupations are significantly more likely to die from coronavirus. ONS data also show that taxi drivers and bus drivers have some of the highest rates of death from Covid-19 among men. Many of these precarious workers risk their lives for low pay and few employment rights.

Furthermore, work precarity induces fear about refusing work. The coronavirus crisis amplifies those threats. If workers cannot afford to self-isolate, the virus is more likely to spread. Offering vulnerable workers more support is therefore crucial — as manifest in The Independent Workers Union of Great Britain (IWGB)’s suit against the Government for its failure to protect millions of precarious workers.

Despite the Government’s response to the coronavirus crisis, many precarious workers are still without adequate support. Normally, precarious workers would be ineligible for universal credit. Although the UK government revised this exclusion, the scheme remains meagre. One person I spoke to waited five to six weeks for her first payment.

Analogous schemes fall similarly short. The Job retention scheme includes those classed as an ‘employee’ under UK tax laws, which excludes many precarious workers. The scheme drew ire because it disbursed money to corporations rather than employees. Under the new self-employment scheme, many have not been receiving income for 3 months. The scheme excludes those who make less than half of their income through self-employment or who recently changed the basis on which they work and therefore covers only 62% of self-employed people. A woman I interviewed was ineligible for the self-employed scheme, as she had been self-employed for only a year. She was also not able to use the Job retention scheme due to the casual zero-hour contract she was on in her second job. She could afford to live off universal credit alone; however, large families, could not.

The coronavirus crisis is putting many more at risk of precariousness. Precarious work spread in the aftermath of the last financial crisis, and the International Money Fund (IMF) predicts this crisis to be the most devastating global economic crisis since the Great Depression.

However, there are reasons for optimism. First, the rhetoric of a ‘safety net’ may be returning to British politics for the first time in decades. Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, spoke in his first budget speech about a ‘strengthened safety net’. Given the previous cuts to social welfare and the shortcomings of government action so far, the possibility for a stronger safety net may seem doubtful; however, social solidarity shown across the UK is undeniable. On a Thursday at 8pm many were applauding NHS frontline staff, carers and all essential workers in this crisis (many of whom are precarious workers). Solidarity is also displayed through individuals coming together to help vulnerable communities. Thus, there is hope that this social solidarity will pressure the government to strengthen the safety net for all.

Second, social solidarity coupled with the fact that more individuals are now at risk of precariousness may galvanise precarious workers to mobilize, influence policy, and demand fairer working conditions. The Trades Union congress (TUC) already encourages this.

Finally, the coronavirus crisis undermines the neoliberal ideology which has dominated the UK’s politics for decades. The idea that we are each individually responsible for our own livelihoods and economic destinies has legitimised an increasingly unregulated labour market and drastic cuts to social welfare. Yet such ideas seem ludicrous when the coronavirus crisis has shown just how interrelated our society is.

Therefore, in the aftermath of this crisis, unlike the financial crisis of 2008, we should heed Polanyi’s (1944) warning: we ought to put human welfare and the natural world at the fore, and strengthen the safety net for all.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

An astute analysis. The question is, haven’t monied interests gummed up the machinery of government too much for any positive momentum in these areas to be sustained? How quickly can you turn around a government that has sustained inequality and itself been sustained by it?