At the height of the first UK lockdown, one message came across loud and clear: Keyworkers are heroes. Nurses and care workers yes; but also delivery drivers, supermarket checkout workers, bus drivers, bin-men, and many more. They are all risking their health and lives (often with no or ineffective protection) to do the jobs required to keep society functioning. And what’s more, they are doing so for precious little pay.

Far more loudly than any deliberate left-wing activism, lockdown seemed to highlight the fundamental injustice of our economic system. Article after article after TV show after radio item – all highlighting how very little we pay people who are suddenly, obviously essential. And how much we pay the bankers, the marketing executives, and the management consultants – whose jobs now seem somewhat superfluous. Posters in every window. Weekly doorstep claps of appreciation. British Vogue, on its July covers, featured not models, but a train driver, a midwife, and a supermarket shop assistant.

So it’s not surprising that many commentators predicted a dramatic shift in our economic attitudes. This is what we expected too, so we decided to check.

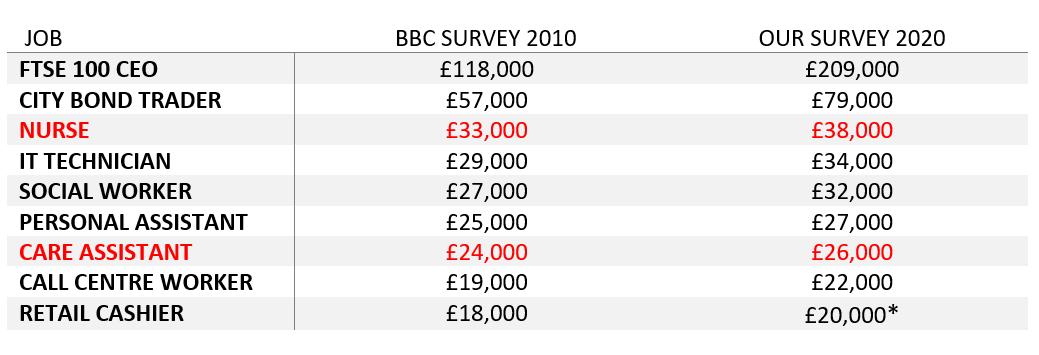

In 2010, the BBC commissioned a survey asking people what they thought a list of different jobs should pay. At the end of May 2020, we commissioned YouGov to ask a representative sample of 1,500 UK residents the same question again for a core set of the same jobs. The survey was conducted online using YouGov’s opt-in panel (for context, the survey took place just as the government’s message was switching from “Stay at Home” to “Stay Alert”, and just before English schools re-opened for some year groups). These are our results side-by-side with the BBC’s from 2010:

*In our survey we asked separately about a clothes shop cashier and a supermarket cashier. The figures were very similar and this is the average of the two.

You can see the full results of the BBC survey here, and the full data from of our survey here.

As you can see from the table, people’s views of what key workers should be paid have not changed since 2010. Care assistants, for example, still rank exactly where they did in 2010 – ahead of call-centre workers, but behind PAs and IT technicians. We also found no evidence that the pay people thought key workers deserved had increased out of line with that of non-key workers.

We also asked our respondents directly if their views about what different jobs should earn had changed due to the pandemic. Consistent with our previous findings, most said that their attitudes hadn’t changed. It is worth noting that many, if not most, people said that this was because they had always thought that (especially) nurses and care workers were underpaid relative to bankers and other ‘fat cats’. However, if the pandemic had strengthened this belief at all, our quantitative results show that this did not manifest in any observable changes in the public perception of rightful hierarchy of pay.

Some respondents drew other key workers (shop-assistants, bus drivers, bin-men, teachers) into the circle of those whom they had always thought were underpaid. However, others made a strong distinction between ‘real’ keyworkers (those working in health and care) and those whom they considered to be less deserving of the label, such as delivery drivers and supermarket staff. Attitudes towards the latter group were occasionally quite hostile, conveying the sense that these workers were elevating themselves to a status they had not earned.

Taken together, our findings caution against the idea that Covid-19 will lead to an inevitable shift in perspectives on work and pay. If a profound change in economic attitudes is going arise from this pandemic, it is unlikely to happen automatically. Those desiring such change will instead have to craft political messages to forcefully bring the economic lessons of the pandemic to the fore.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments