Lexi Aisbitt asks how Muslims experience belonging in the changing borderland landscape of West Bengal.

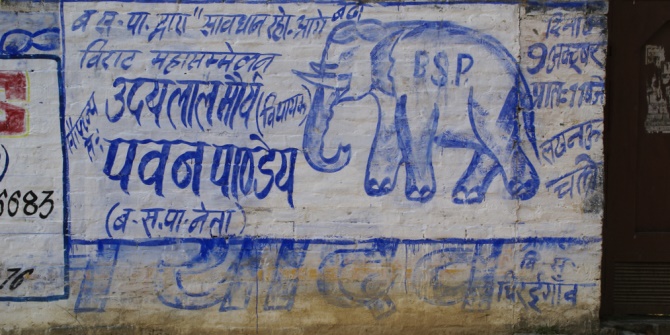

At the fringes of the West Bengal landscape, change is both occurring and noticeably absent. A recent state-wide political power shift has produced much heralded developmental improvements, but these initiatives contrast starkly with the deployment of the same brutal political tactics as in the past. It is claimed that a legacy of social and economic deprivation is gradually being eroded by ambitious infrastructure projects—the tangible results of which, however, remain to be seen. Escalation in communal tension, the threat of ecological degradation, and increased state security against the threats of terrorism, piracy and illicit trade have brought a further sense of foreboding to the borderland.

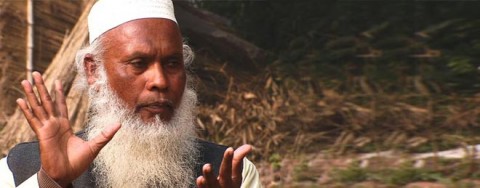

Muslim inhabitants of this part of West Bengal occupy a number of geographic and conceptual boundary zones. At the margins of the state and the nation, as members of India’s largest and most controversial religious minority, resolutely Bengali and unflinchingly Islamic, how do these borderland Muslims understand and enact their capacity to belong within an ever-shifting social and political landscape?

In the scrubby patch of ground behind the tightly clustered houses, the women soon begin to discuss politics. Sitting on plastic chairs in the warm winter sun in this village two hours south of Kolkata, the conversation quickly turns to the Lok Sabha elections and voting options. The years of Left Front rule are vocally denounced as political stagnation, whilst the superficial benefits targeting minorities that Muslims have enjoyed under the recently elected All India Trinamool Congress party are praised but tentatively, reflecting the cloud of possible future disappointments. These women are aware of the emerging Islamic political parties in West Bengal but appear disinterested in what they have to offer. They seem to eschew the communal political predilections to prioritise religious identity in choosing their party, which are so visible elsewhere in India, in favour of more pragmatic assessments of who stands to deliver the greatest developmental benefits for them and for their families.

The animated confidence of the political debate quickly ebbs when I ask about the partition that split East and West Bengal some 67 years ago. The women’s memories appear vague and they profess to know little about what happened, or why. After a pause an elderly woman to my left quietly states that she lost her grandfather in the events of partition, and that he was murdered in the brutal communal violence that engulfed Kolkata as well as other parts of India, spreading across the newly demarcated borderlines into neighbouring Pakistan. She glances at me and projects a stream of crimson paan spittle into the dust before saying, “We, as people, don’t feel different. It is the politicians, the newspapers who stir these things up. We know we are all the same.”

These preliminary encounters suggest an intriguing juxtaposition of a tangible sense of difference yet an emphatic feeling of belonging for Muslims in West Bengal. My research intends to explore the emerging gap between how the capacity to belong is represented by the state, political parties and the media, and how it can be observed in the everyday practices that both constitute and engender the capacity to belong amongst these individuals. As such, I want to investigate and understand the moments and events at which these feelings pertaining to the capacity to belong are more heightened and the points of reference for these individuals that possess the most meaning. What role do histories, memories, folklore or kinship, traditionally understood as the location of culture, play in influencing current praxis and shaping understanding of an ability to belong in the future, and who has the right to define and articulate the capacity to belong for Bengali Muslims?

Although simultaneously beyond the limits of state provision yet highly scrutinised due to their proximity to the border, it is tentatively suggested that a dynamic resilience exists in which alternative networks and diverse registers are deployed and negotiated to protect livelihoods and produce stability amongst borderland Muslims. Though unable to be captured by the stock images of development, equality or a homogenous national identity, the diverse experiences of these individuals may illustrate that existence upon the margins may represent an opportunity to construct and perform novel, dynamic and diverse ways of belonging.

The considerations which form the overarching questions for my research are: How is the capacity to belong understood by Muslims inhabiting the West Bengal borderland? What are the forms of relatedness in terms of kinship ties, livelihood strategies or historical or memory connections in which this capacity to belong is made manifest? And what role might geographic and conceptual boundaries, the political imagination of both the state and individuals, and temporality play as reference points in the embodiment of belonging?

Over the next two years I will be undertaking 18 months of fieldwork in rural West Bengal in pursuit of answers to these questions, amongst many others. Residing in a small town located in the India-Bangladesh borderland, I intend to deploy the varied tools of ethnography whilst endeavouring to immerse myself in the dynamic and evolutionary process that Magnus Marsden has referred to as ‘living Islam’. In doing so, I hope to gain insight into this borderland West Bengali Muslim population, who are themselves just one element of a myriad of Indian Muslim identities.

About the Author

Lexi Aisbitt is a doctoral candidate in LSE’s Department of Anthropology.