On 25 February 2015 Vivek Srinivasan, Liberation Technology Program Manager at Stanford University, gave a talk at LSE entitled “Can Modi dismantle India’s welfare programmes?” Drawing on fieldwork conducted in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, he argued that sustained local-level popular demand for basic services mean that attempts by the government to reduce support are unlikely to prove sustainable in the long run. Sonali Campion reports on the event.

On 25 February 2015 Vivek Srinivasan, Liberation Technology Program Manager at Stanford University, gave a talk at LSE entitled “Can Modi dismantle India’s welfare programmes?” Drawing on fieldwork conducted in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, he argued that sustained local-level popular demand for basic services mean that attempts by the government to reduce support are unlikely to prove sustainable in the long run. Sonali Campion reports on the event.

What creates political commitment to public services in Tamil Nadu? In a recent talk at LSE, Dr Vivek Srinivasan drew on his PhD to consider how far the current government’s commitment to reducing public services is likely to impact on poor people’s access to state support in India. The research stemmed from his time working on the Right to Food Campaign in India, where Vivek noticed that despite guarantees, states in the northwest of India were struggling to implement free school meals. This contrasted with the situation of Tamil Nadu which had been providing not only school meals but also other public services such as electricity and water much more effectively for two decades.

A number of leading academics working on India have offered explanations for the effective public service delivery associated with southern states such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu. For example, Amartya Sen and Jean Drèze have emphasised the role of women’s agency, while Atul Kohli and Patrick Heller have cited the history of strong left movements, organised parties and collective action and Barbara Harriss-White has pointed to the significance of low caste-led government. On the basis of 13 months of fieldwork, however, Vivek asserted that the real difference in Tamil Nadu was the sustained daily public action, typically initiated at village level but mobilising wider networks, such as political parties. He argued that most services now enjoyed by villages in Tamil Nadu would never have happened automatically, they are gained gradually:

“They will have struggled for two or three years…then they will get one water tank. Another year they will have struggled and they will have got twenty streetlights, another year they would have struggled and got 100m of road. In that sense there was a history of struggle for every single public service that was there”

In any single year, the gain is minimal but the cumulative affect over 20-30 years is remarkable. Vivek indicated the decentralised nature of protest is critical to understanding Tamil Nadu’s success.

Vivek offered a vivid insight into the nature of protest in Tamil Nadu. Most protests are initiated by young men educated to high school or even graduate level. While women participate vigorously in local protests, the number participating in action and district level or above declines dramatically. The protests often centre on demand for facilities, whether it is water tanks, buses or road improvements. However, many focus on facilitating access to existing resources, such as female or lower caste access to schools.

In a particularly entertaining section of the presentation, Vivek described the creative forms of protest observed during his fieldwork, many of which are unique to Tamil Nadu. For example, to demand road improvements “paddy planting” is used and rice saplings are planted in the cracks in the road to highlight the state they are in. “Pot breaking” has become common in protests about access to water. In the first instance, pots are strung across the nearest main road, obstructing traffic and indicating to the wider population that a protest is in progress. If this combined with traditional petitioning is not effective, protestors take their pots to the district office and smash them on the gates. The pressure to modify rules is therefore continuous and intense. Later he also referred to cases of old women with seemingly limited bargaining power, who simply sit outside the relevant official’s house until action is taken to give them their pension.

The current culture of protest is a relatively recent phenomenon. Even 30-40 years ago lower caste groups, particularly bonded labourers, could not protest as even minor infractions would result in serious punishments. Vivek emphasised that escape from bonded labour was also a process that required prolonged struggle: Dalit groups had to mobilise collectively to resist violence and earn independent means of income, for example through rearing goats. Other early demands centred on issues such as access to temples, or being served food in a dignified manner (caste practices traditionally dictated that Dalits could not be given food in bowls because it was thought they would “pollute” the vessels). Campaigns for services today are therefore a continuation of this quest for dignity and equal treatment. The demanding for services has also been a demand for political power, which has translated into lower caste representation in key arenas such as the District offices and Panchayats.

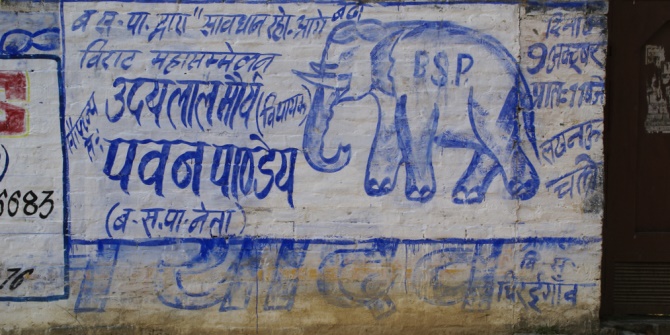

Elections also give protestors greater power. Local elections in particular can be won or lost with 3-4% of the vote so the support of even small communities is significant. District presidents know there are many willing to replace them, but also that they will be punished at the polls for delivering services to some but not others. This creates the pressure to deliver services “not just to a few, but also universally”, incentivising the state government to design programmes that will reach a large number of people and function well. Intense political competition is therefore also key to Tamil Nadu’s success in delivering public services.

Turning to the bigger picture, Vivek identified three categories of public service performance in India: exceptional, mediocre and poor. The ‘exceptional states’ – namely Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Himachal Pradesh – are not the richest states but appeared to target their expenditure more effectively than poor performers such as Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa and Rajasthan. However, Vivek suggested the transformation associated with the south is increasingly being seen in the north, with states like Bihar making real improvements in terms of delivering roads, education and health as a result of social organisation similar to that which has been seen in the south.

Vivek concluded by returning to the question of whether neoliberal ideologues calling for the elimination of public services are likely to have negative impact. He quoted former Chief Minister of Bihar Lalu Prasad Yadav “Swarg nahin, swar diya hai” – “I may not have given people heaven but I have given them voice” and argued you cannot give people a voice but continue to deny them heaven forever. Social transformation is a product of voice. The current government’s promises to dramatically improve lives by reducing corporation tax and offering land at a cheap rate to foreign companies that will create employment opportunities and foster mobility. But on a local level, particularly in rural villages, it will still not be possible to ignore the vocal demand for basic services. Vivek therefore insisted that while the current government may seek to implement changes and cuts, the reduction of services cannot be sustainable in the long run.

Dr Vivek Srinivasan is a social scientist working with the Program on Liberation Technology at Stanford University. He obtained his PhD in Social Sciences at Syracuse University prior to which, he worked as the coordinator of India’s Right to Food Campaign. He is the author of Delivering Public Services Effectively: Tamil Nadu and Beyond.

Image credit: flickr/Ajay Tallam CC BY-SA 2.0

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the India at LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Sonali Campion is Editor of the India at LSE blog. She tweets @sonalijcampion.

Sonali Campion is Editor of the India at LSE blog. She tweets @sonalijcampion.