The Bihar election results announced earlier this month revealed a decisive victory for Nitish Kumar and Lalu Prasad Yadav’s ‘Mahagathbandhan’ (Grand Alliance), while the BJP and its allies were soundly defeated. Pranav Gupta offers an overview of the results and analyses the likely contributing factors as well as the longer-term implications of the victory.

The Bihar election results announced earlier this month revealed a decisive victory for Nitish Kumar and Lalu Prasad Yadav’s ‘Mahagathbandhan’ (Grand Alliance), while the BJP and its allies were soundly defeated. Pranav Gupta offers an overview of the results and analyses the likely contributing factors as well as the longer-term implications of the victory.

Bihar continued the ongoing trend of giving decisive verdicts as the Grand Alliance of Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), Janata Dal (United) (JDU) and the Congress won 178 out of the 243 seats in the state. The BJP faced a second successive defeat after Delhi and was reduced to just 53 seats. Its allies – the Lok Janshakti Party, the Hindustani Awam Morcha and the Rashtriya Lok Samata Party won just 5 out of the 86 seats that they had contested. In this article, I would provide a brief overview of the result and then re-look at how the probable factors I identified as polling began played out in the election. At the end, I will briefly comment upon some broader long term implications.

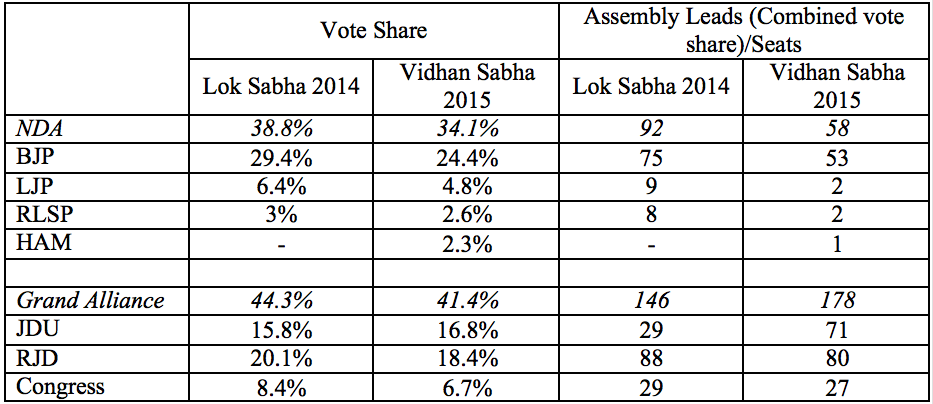

In terms of seats, the three parties which formed Grand Alliance to contest the election this year surpassed their 2014 Lok Sabha election performance. The NDA had led the Grand Alliance parties on 92 seats in 2014. The prime reason for this is the rise in the vote share gap between both alliances from 5.5 percentage points to 7.3 percentage points. This has occurred despite a decline in the absolute vote share of both alliances. The Grand Alliance’s vote share this time was 44.1 percent as compared to 44.3 percent in 2014. Similarly, the NDA’s vote share came down by close to 5 percentage points from 38.8 percent to 34.1 percent. The NDA suffered a vote share decline despite the addition of a new partner.

Table 1: Party-wise performance Lok Sabha 2014 and Vidhan Sabha 2015

The magnitude of the BJP’s defeat is such that it cannot be merely considered to be an outcome of adverse arithmetic. The BJP won 49 seats in the 2010 Assembly election and the NDA had a higher vote share than the Grand Alliance in 2014. The NDA managed to retain only 22 of their ‘stronghold’ seats. The 27 seats lost by the BJP mainly went to the RJD (14) and the Congress (9).

This indicates that the BJP lost its core seats in the state. Among urban voters, the NDA’s lead was much lower than what they would have expected. The Alliance managed to win 17 out of the 30 seats urban seats in the state. But among rural voters, the NDA lagged far behind as the Grand Alliance had a lead of more than 9 percentage points in terms of votes. The failure to emerge as the single largest party in the house (in terms of seats) is a major setback for the BJP which was hoping to at least establish itself as the principal player of Bihar politics. I would now discuss some factors which proved to be decisive.

First, the forces of Mandal and Kamandal did influence the election and it seems that the latter was clearly overpowered by the former. The Grand Alliance registered a decisive victory not only because it was able to maintain its existing social coalition but also because it managed to fragment support among social groups leaning towards the BJP. The NDA was hoping to counter the Grand Alliance’s Muslim-Yadav alliance through a consolidation of upper caste and Dalit votes. However, the much-discussed Dalit consolidation for the NDA never materialised. The alliance could manage to win only 7 out of the 38 seats (BJP – 5 out of 21; Allies – 2 out of 17) reserved for Scheduled Castes in Bihar. The vote share gap between the NDA and the Grand Alliance was relatively higher in SC reserved seats. While the NDA led among the Paswans, the Mahadalit vote got fragmented between multiple players. As per the Lokniti-CSDS Post Poll survey, 51 percent of the Paswans voted for the NDA but this was much lower than 2014 when more than two third of the Paswans had supported the alliance. Similarly, only 30 percent of the Mahdalits voted for the NDA which was much lower than the Lok Sabha election. Further study is required important to understand what led to this last moment fragmentation of Mahadalit vote as the BJP seemed set to consolidate support among them till September.

Much has been written on how Kamandal/Hindutva element in the BJP’s campaign backfired and became a cause for the party’s loss in Bihar. I believe that the party lost despite it rather than because of it. Prime Minister Modi started talking about Nitish and Lalu’s minority reservation promises to counter the Alliance leaders on Mohan Bhagwat’s reservation remarks only during the later phases of the election. It is not as if the contest was close until then as the BJP trailed massively even in the first two phases. The absence of a Mahadalit consolidation in favour of the BJP made the question of Extremely Backward Castes (EBCs) being pivotal almost irrelevant. If the BJP had managed to gather high support among the Mahadalits, then the voting decision of the lower Other Backward Castes (OBCs) could have determined the election. But this group, which forms close to a quarter of the state’s electorate, is extremely heterogenous and voted in a fragmented manner. The NDA enjoyed a lead of just 8 points among them, winning 43 percent of votes. This was 10 percentage points lower than 2014 and partially explains why the party lost so decisively.

Second, such an election victory would not have been possible without a strong transfer of support between parties. For the first time since 1990, Kurmis and Yadavs in Bihar voted on the same side. Lalu Prasad Yadav and Nitish Kumar managed to ensure a transfer of support despite mutual distrust among the cadre. Prof. Sanjay Kumar and Shreyas Sardesai estimate using survey data that 60 percent of the Yadavs voted for the JDU in the constituencies that it contested. The transfer of Kurmi votes was better as the Grand Alliance’s vote share among them was almost equivalent in seats contested by both RJD and the JDU. The two parties were able to gradually change the negative perception about their alliance. This was evident in the post-poll survey as more than four out of ten voters said that there was nothing wrong in the coming together of both parties, this was almost 10 percentage points higher than the pre-poll perception. Still, what is interesting is that there was no drastic change in the negative perception of Lalu Prasad Yadav. Even in the post-poll survey, 44 percent of the voters said that they disliked him. Nitish’s positive image among the voters probably provided a counterbalance and it helped the Grand Alliance to win over swing voters. 27 percent of the Grand Alliance voters said that they would have voted differently if Nitish would not have been the Chief Ministerial candidate.

Third, it would wrong to look at this election only through the prism of caste and religious identities. The Grand Alliance would not have been able to win such a massive mandate through social mobilisation alone. Nitish Kumar’s positive performance appraisal clearly helped the alliance. Close to 80 percent of Bihari voters were satisfied with the work done by his state government. The level of satisfaction with the central government was marginally lower at 72 percent. As in Delhi, the ‘Modi magic’ was unable to counter a popular regional leader. Does this indicate the emergence of divergent voting patterns in state level and national elections?

needs to revisit its strategy of fighting state elections. It was unable to even fulfil its second best scenario of emerging as the single largest party and establishing itself as the central force of Bihar politics. Is it that the BJP’s promise to voters in the state has become limited to the presence of cooperative central government and a helpful Prime Minister? The BJP has been unable to convince voters about the impact of having the same party at the state and the centre. It must be able to show what difference the party’s presence at the centre made to the development of Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Gujarat, which were under its rule during the UPA era. Fighting as the central incumbent it also needs to show some evidence of results on the promises of 2014.

The JDU and the RJD now need to enter into governance mode and ensure that their unlikely reunion remains stable. Nitish Kumar will have to remain focused and ensure that no controversy diverts him from the agenda of governance. Despite any internal issues arise, the alliance is likely to survive as both parties are unlikely to have any alternative. In case of a midterm election, the BJP would start well ahead as the favourite.

The guest list at Nitish Kumar’s swearing in ceremony clearly indicates the future course of national politics. The BJP’s rise to power started from the states as its Chief Ministers consolidated support in their respective states through a good performance. The opposition to Narendra Modi at the moment also seems to be coming from the states. In the near future one could expect greater political coordination among Non Congress-Non BJP Chief Ministers with complete support from a weakened Congress to take on the larger common nemesis – Narendra Modi and the BJP.

On 9 November Pranab Gupta participated in the South Asia Centre’s Global Hangout Discussion with experts including Giles Veniers, Jeffrey Witsoe, Manisha Priyam, Milan Vaishnav, Neelanjan Sircar, Pranav Gupta, Sarthak Bagchi. View the event video here.

Cover image credit: flickr/Goutam Roy CC BY-SA 2.0

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Pranav Gupta is currently pursuing MSc. in Political Science and Political Economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Previously he worked as a Reseach Assistant on the Lokniti Programme at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in New Delhi.

Pranav Gupta is currently pursuing MSc. in Political Science and Political Economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Previously he worked as a Reseach Assistant on the Lokniti Programme at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in New Delhi.