Srishti Agnihotri and Minakshi Das discuss the tendency to effect legal reform as a response to a singular, highly emotive event. The gang rape of a 23-year old student on 16 December 2012 not only resulted in reform of laws relating to sexual violence, but also the rules around juvenile justice in the lead up to the release of the young offender who participated in the rape. They argue that juvenile justice should seek to rehabilitate and prevent further crimes, and question whether the new legislation prioritises these aims.

We still remember the evening of 16 December 2012, and its aftermath. The next weeks were spent following the coverage of the brutal gang rape of a young girl, who became etched in public memory as ‘Nirbhaya’ [Fearless] because of the courage with which she fought for her life.

It is understandable why people wanted an instant change in the law following the incident. In fact, laws relating to sexual violence were in dire need of a reform. The changes that were eventually made had certain much-needed features, like an expansion of the ambit of rape, and defining offences such as stalking and voyeurism. However, they had some problematic features too, for example the provision for mandatory minimums and statutory rape, that did not take into account the need for age proximity clauses. As a result, they are a good example of the worrying tendency to effect legal reform as a response to a singular, highly emotive event.

The Rajya Sabha has recently passed The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Bill 2015, which many feel is a response to the release of the juvenile who was convicted of committing the 16 December gang-rape.

The Bill is comprehensive and a ‘nuanced one’ (according to the Minister for Women and Child Development). However, it contains a controversial provision which allows 16 years olds to be tried as adults if they have committed a ‘heinous offence’, defined as one for which the minimum punishment under the Indian Penal Code or any other law is imprisonment for 7 years or more. This issue has polarised people, and sparked a debate on whether this Bill is regressive and reactionary. We thought this was a good time to look into the deliberative/legislative process behind the passing of this bill.

Regressive or responsive?

Shashi Tharoor, in his speech on the Bill, provided a scathing indictment of its provisions, and stated that ‘It’s a bad law, badly written, and badly thought through’. He drew on the provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, and provisions of our own Constitution, to argue that the provisions of the Bill would end up embarrassing India before the international community. His fears are not incorrect, since a reading of Article 2 of the UNCRC shows that the principle of non-discrimination enshrined in it does enjoin the state to treat all children in conflict with law equally.

Not all parliamentarians were as critical of the bill, however. Rajeev Chandrashekhar, who has been a strong pillar of support for victims of child sexual abuse, talked about the need for protecting victim’s rights as well as the children’s rights. He stated that the Parliament should have passed the bill earlier, which would have been more responsive to the sentiments of the people of India. He mentioned that the definition of heinous offenses was too broad, and in should be restricted to the categories of ‘rape, murder, kidnapping, trafficking and terrorism’.

K.T.S Tulsi provided a comparative analysis with other countries, and stated in his speech that he felt the bill erred on the side of caution, and did not in any way compromise child rights.

The CPI (M) walked out in protest against the Bill, and Sitaram Yechury bemoaned the fact that the Bill was not deliberated upon in a more ‘dispassionate and scientific’ manner.

The myth of the prowling juvenile

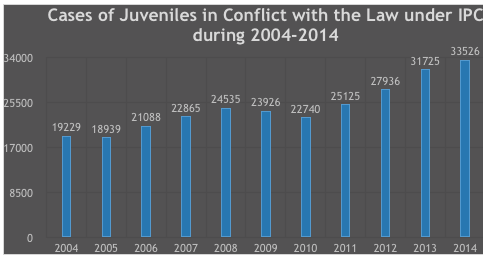

One argument of those supporting the Bill is that there is an alarming spike in crimes committed by juveniles. Let us examine the veracity of this claim. The NCRB data shows that in terms of overall crimes committed by juveniles under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), during the period of 2004-2014, there has been a significant increase. This suggests that crimes committed by juveniles are becoming a serious issue. However, it is important to keep these figures in context. According to PRS Legislative Research, ‘over the last ten years (2003-2013), crimes committed by children as a percentage of all crimes committed in the country, have risen from 1.0% to 1.2%’.

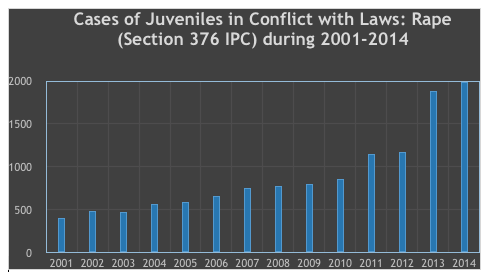

If we narrow it down to crimes committed under Section 376 of IPC, the rise is steeper. However, we cannot rule out the role played by other factors such as increase in reporting, general awareness, and the expanded ambit of rape in the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 2013.

If we look at the category of ‘gang rape’ committed by Juveniles in the NCRB data, we see that states like Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh are problem areas. Similarly if we look at gang rape committed in Union Territories, the capital stands out as an outlier. We need to analyse what factors contribute to make some states real problem areas.

The idea that juveniles are used by gangs to commit organised crimes, precisely because juveniles will not face stringent punishments, has gained momentum. But even if this is accepted, concluding that some juveniles to be tried as adults is an abdication of state responsibility. It is the job of the State to ensure that law and order is maintained, and that organised gangs are not able to exploit children. Our efforts would be better utilised in trying to check this tendency, rather than penalising the juvenile.

Further, there may be cases where young people (say a 17-year-old boy and a 15-year-old girl), engage in ‘consensual’ sexual activity. Cases of young people experimenting or falling in love can no longer be brushed aside. Since the provisions of the POCSO Act do not recognise a child’s consent, the 17-year-old boy could potentially be tried as an adult. While both the male and female children in such a case are technically Children in Conflict with Law (CCL) and Children in need of care and protection (CNCP), the police invariably treats the male child as a CCL and the girl child as a CNCP. We need to examine whether the new law is open to abuse on this front. If it is, then certain safeguards will have to be provided. (This might include introducing age proximity clauses in case of statutory rape, and/or narrowing the ambit of heinous crime).

What does justice hope to achieve?

There are many competing visions of justice. One such vision is restorative justice (RJ) based on the principles of ‘repair, involvement, and justice system facilitation’. RJ wants to enable ‘offenders to understand the harm caused by their behaviour and to make amends to their victims and communities’. It envisions ‘giving victims an opportunity to participate in justice processes.’ Finally it aims at protecting the public through a process in which the individual victims, the community, and offenders are all active stakeholders.

In this light the new Bill is conceptually flawed. Its intention is to punish those who have committed heinous crimes, while its focus should be on alternative treatments (such as reformation, rehabilitation and re-integration with society). According to Professor B.B. Pande, who was on the drafting committee of the Juvenile Justice Act of 2000, the CCLs in the 16-18 year age group targeted by this Bill are of a relatively small number, and could be rehabilitated through sustained individual care and preventive programmes. This approach has been trialled in Germany and proved effective at preventing young people from re-offending. The idea is not to establish harsher or milder punishments, but rather having an effective system that would lead to fewer victims. We must note that a lot of children in conflict with law are most likely in need of care and protection, and have been drawn to crime precisely because this is missing.

Cover image: Protests following 16 December rape. Credit: flickr/Ramesh Lalwani CC BY-SA 2.0

This article originally appeared on The Wire and is reposted with permission. It gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Srishti Agnihotri is a criminal lawyer practicing in New Delhi, India. She completed her Masters in International Human Rights Law from the University of Notre Dame, USA.

Minakshi Das is an LSE alumna working at Zee Media Corporation Lmt. as a Legal Associate (legal, research and media). She is also engaged research and advocacy in the field of child rights.

Both authors write here in a personal capacity.

Who is a “juvenile” according to common sense and not according to the so called CCL and intellectuals? Is one at 17 years and 10 months a juvenile and does he become a non-juvenile when he is 18 years and one month? What is the basis for this theory? Some obscure and non-representative biology experiment?

To be practical is not to be dubbed as “knee-jerk” or “emotional”. Why should not culpability and punishment be more severe in what is considered in common sense as “heinous” crime?

This “rehabilitation” theory is being taken to extremes, even as “Human Rights”. Is there some reliable and representatively relevant statistics on the impact of “rehabilitation” and “retribution” in crimes adjudicated?

Lastly crime and punishment should not be divorced from cultural and traditional taboos. What is considered great in Germany or UK or the US need not be ipso facto accepted in India.

R.Venkatanarayanan