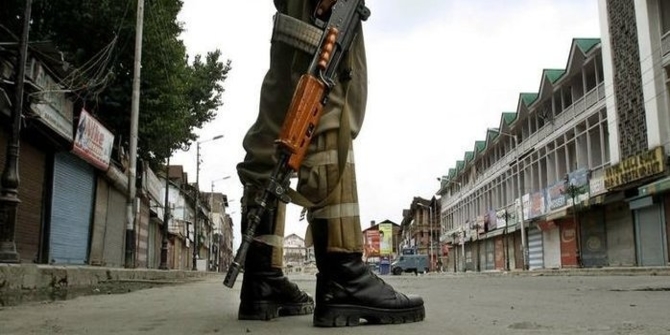

S. Mahmud Ali looks back on what proved to be a turbulent and often difficult year for Pakistan. Renewed Islamist violence shook the civilian government’s authority, tensions with India rumbled on, and Islamabad’s Afghan policy was coloured by profound insecurity. The year was not without its positives, most notably Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit which was coupled with promises of substantial investment. However, as 2016 gets under way it remains to be seen whether Pakistan can prevent the multiple threats it faces from escalating.

2015 was a turbulent year for Pakistan. A bloodbath at a Peshawar school in December 2014, where Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) assailants killed 145 people, mostly children, darkened the augury for 2016. Seen as a response to counter-TTP military operations in North Waziristan, the blitz on an army-run school inside Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province’s major garrison triggered a 20-point National Action Plan.

Islamabad reinstated the death penalty, beginning with the execution of around 500 death row convicts. The army boosted its Zarb-e-Azb and Khyber-I operations, and military-run anti-terrorism courts speeded up trials. Taliban militants responded by spilling more civilian blood. Fearing retribution, thousands of Afghan refugees fled back across the Durand Line.

Outrage united an oft-divided Pakistan. Opposition leaders Imran Khan and Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri ended their campaigns against Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. But Sharif’s authority in national security and strategic diplomacy suffered grievous erosion. Demonstrating their resilient vigour, TTP militants continued attacking ‘soft’ targets, notably a mosque at another Peshawar garrison.

Pakistan’s economy, too, presented a mixed picture. With its GDP growing at only 4.4 per cent, exports falling and inflation declining, Islamabad faced major challenges. To complicate matters, Pakistan’s population is expected to reach 227 million in 2025 with 63 per cent below age 30. Acute energy shortages, a low revenue base, modest infrastructure, poor public health and educational services as well as continuing insecurity threaten Pakistan’s prospects. Yet the one bright spark of 2015, a promise of US$46 billion in investments, flashed during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit.

Xi pledged to help build the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) — a road and railway network linking China’s Xinjiang province with Balochistan’s Chinese-built and operated Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea. Of this US$46 billion, US$37 billion would be dedicated to rebuilding Pakistan’s anaemic power infrastructure. If fully implemented, the CPEC promises to partially transform Pakistan into a commercial powerhouse, enriching itself by extending China’s geo-economic reach. But insecurity challenged the vision.

This Chinese financial sunshine contrasted with Indian diplomatic clouds. Sharif met his Indian counterpart, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, at a summit in Russia. At the summit, both countries became full members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and agreed on a five-step plan to restore a ‘normal’ relationship.

But the first of these steps, a meeting between National Security Advisers (NSA), was aborted when the Pakistani NSA insisted on meeting a Kashmiri separatist leader. Meetings with separatist leaders have previously been common practice as Islamabad considers them to be key stakeholders in the dispute. This time round, Delhi stated that any meeting with Kashmiri separatists would be ‘inappropriate’.

The two countries’ perspectives sharply diverged: Delhi focused on alleged Pakistan-based terrorist attacks on its territory, including in the disputed and divided Kashmir, before addressing anything else. Islamabad sought broad-based negotiations with Kashmir as a top priority. This rendered normalcy an elusive goal.

The geopolitical ramifications were significant. Pakistan announced a ‘breakthrough’ deal to procure attack helicopters from the historically India-friendly Russia, Indo–Russian friendship having cooled following over a decade of intensifying US–Indian strategic collaboration. Two months later, protracted negotiations culminated in another agreement. Russia, with Chinese help, would build and operate the 1100-kilometre North–South gas pipeline linking the port city of Karachi with the centre of national political gravity, Punjab’s provincial capital Lahore. Indian commentators had postulated the emergence of a Russia–China–Pakistan strategic triangle, with potentially adverse implications for India, since late 2014 when major accords were announced.

These manoeuvres apparently strengthened Nawaz Sharif’s weak diplomatic hand during his October visit to Washington, where he stressed Pakistan’s India-rooted anxiety. Sharif urged equal treatment: Pakistan sought a nuclear agreement similar to the landmark 2005 US–Indian accord, which tacitly acknowledged India as a nuclear-weapons state and offered significant technological security concessions. The US pledged continued military assistance to Pakistan but the countries did not come to an agreement on the nuclear issue or on Kashmir.

Given the improbability of an offer comparable to that given to India being made to Pakistan, Sharif rejected US pressure to reduce Islamabad’s tactical nuclear weapon stockpiles. Pakistan had been fabricating stockpiles of these highly destabilising weapons in a plan to deter India’s so-called ‘cold start’ operational plans. These purportedly enabled Delhi to initiate swift armoured-aerial thrusts deep into Pakistan’s narrow, elongated territory in a decapitating first strike. The risks of a nuclear exchange devastating South Asia cast a pall far beyond the subcontinent.

Profound insecurity also continued to colour Islamabad’s Afghan policy in 2015. Covert intervention sponsored by the United States, Saudi Arabia and other partners to deploy Islamist Jihadist paramilitaries against Soviet occupation forces in the 1980s lay the foundations for much of this continuing insecurity. Islamabad has been deeply concerned with achieving ‘strategic depth’ by ensuring there is a friendly government in Kabul. This is designed to preclude the possibility of double envelopment by Delhi in the event of an armed conflict with India.

Bereft of foreign patrons in this quest, Islamabad engaged with President Ashraf Ghani’s government. Islamabad further covertly protected the Afghan Taliban’s Shura, sponsored Taliban–Kabul negotiations as well as supporting both Qatari and Chinese mediation. And, at the same time, it hunted Afghanistan-based TTP militants.

As the October earthquake demonstrated, Pakistan and Afghanistan remain inseparable. With the NATO International Security Assistance Force drawdown, the Taliban’s resurgence and diplomacy hobbled by a turbulent succession battle following revelations of former Taliban leader Mullah Omar’s death, Islamabad stands at an Afghan crossroads with few clear options.

Internally polarised, hemmed in by unfriendly neighbours and with its modest resources drained in a perennial search for security, Islamabad faces a fork in the strategic road. If deterrence proves effective and Sino–Russian aid reinvigorates the economy, Pakistan could muddle along. But if its unremitting struggle with Islamist militancy fails, or its fundamental fear of India catalyses a strategic spiral, all bets will be off.

Image credit: Sonali Campion

Note: This article originally appeared in December 2015 on the East Asia Forum blog and is reposted with the author’s permission. It gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

S. Mahmud Ali is East Asia International Affairs Programme Associate at LSE IDEAS