Last Saturday, the eminent philanthropist and founder of the Edhi foundation, was laid to rest with great ceremony. Here, Usama Khilji offers an obituary of Abdul Sattar Edhi and his lifelong commitment to delivering secular welfare support to those neglected by the state.

Last Saturday, the eminent philanthropist and founder of the Edhi foundation, was laid to rest with great ceremony. Here, Usama Khilji offers an obituary of Abdul Sattar Edhi and his lifelong commitment to delivering secular welfare support to those neglected by the state.

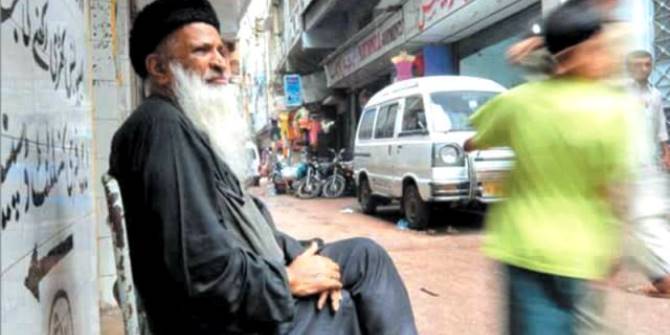

Pakistan’s iconic philanthropist Abdul Sattar Edhi passed away in Karachi at the age of 92 on 8 July 2016, and was accorded the first state funeral in Pakistan in 30 years. Edhi embodied selfless humanitarianism, providing welfare without discrimination to the downtrodden in a nation-state of 200 million that has struggled politically amidst a civil-military rivalry marred by corruption and coups. In many ways, the Edhi Foundation stepped in to fill in the gaps to serve people – free of cost – left behind by the state.

Edhi was born in 1928 in what is now the Indian state of Gujarat. His mother was paralysed when he was 11 and later developed mental ill-health so he became a full-time carer at a very young age. According to his profile on the Edhi foundation website, his mother passed away when he was 19, and this made him think of the millions others that have long-term health problems but nobody to care for them. After migrating to Karachi, Pakistan with his family during the partition of India, Edhi briefly worked as a peddler and then sold cloth in market before quitting and raising funds by begging to set up a free medical dispensary. Soon afterwards, he set up the Edhi Trust, a welfare centre with a maternity home and an emergence ambulance service.

Edhi’s ambulance service expanded rapidly due to an outpouring of donations from citizens across Pakistan. By 1997, the Edhi Foundation was noted for having the largest number of private ambulances in the world – with a 1500-strong fleet. This has risen to over 1800 ambulances and 335 Edhi Centres across the country today. Other services that Edhi spearheaded include: “free shrouding and burial of unclaimed dead bodies, shelter for the destitute, orphans and handicapped persons, free hospitals and dispensaries, rehabilitation of drug addicts, free wheel chairs, crutches and other services for the handicapped, family planning counselling and maternity services, national and international relief efforts for the victims of natural calamities.”

Edhi centers across Pakistan also feature small cribs outside the premises with a notice that says “please don’t dump babies, leave them here”. It is taboo to conceive children outside of marriage in Pakistan, which has resulted in people dumping newborns to die. Edhi observed this trend personally and he decided to adopt them in Edhi homes. The cribs are now well-known and there are reported to be more than 20,000 children in Pakistan officially registered with Edhi’s name as their father.

In the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Edhi’s humanitarianism had no religion. The Edhi Foundation’s motto is “Serving Humanity in the Spirit of All Religions”. He has been criticised by right-wing Islamic clerics for helping non-Muslims; once asked why he transports Hindu and Christian dead bodies, his response was “Because my ambulance is more Muslim than you”. He is also reported to have said “My religion is humanity”. Such secular humanitarian practise is exemplary and needed in a country where religious minorities have been under attack especially in the last decade by extremist militants. His foundation has been active in providing relief during natural calamities as well. For example, they donated $100,000 for relief to survivors of hurricane Katrina in the U.S., and is currently involved in relief efforts following the earthquakes in Nepal.

Edhi was also an avowed socialist, said to have read Lenin and Marx, and he received the Lenin Peace Prize in 1988 for his social and humanitarian work. He only took donations from private individuals and entities, refusing funding from the state, including from Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi who offered Edhi foundation 10 million Indian rupees in October 2015 after it had provided shelter and care to an deaf and mute Indian girl, Geeta, who had been separated from her family after reaching Pakistan on a train from India and stayed for a decade. Earlier this year, former Pakistani President Asif Zardari also offered to organise for Edhi to go abroad for treatment for his kidney ailment, but the philanthropist refused, choosing to get treatment in Pakistan. This was especially symbolic, because Pakistan’s political elite is criticised for flying abroad for medical treatment rather than using and improving healthcare facilities at home. Most recently, the Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif has faced criticism for staying in London for over a month for his heart surgery.

Edhi was a strong advocate for organ donations, and he has practiced what he preached. Due to his illness, many of his organs were unfit for transplant but his corneas have been donated to a visually impaired man and women who were awaiting eye donations.

Pakistan lost a legendary humanitarian worker with the passing of Edhi, but his legacy lives on through his dedicated wife and children that now run the large network of Edhi centers and ambulances across Pakistan. The Pakistani government accorded a state funeral to Edhi, now it must act to provide social welfare services to its downtrodden citizens without discrimination as the Edhi foundation has independently made possible.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Usama Khilji is an activist and Chevening Scholar from Pakistan pursuing an MSc in Comparative Politics at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His interests include minority rights, online censorship, civic education, reform in Pakistan’s tribal areas, and peace in South Asia. He tweets @UsamaKhilji and blogs at usamakhilji.com.

Usama Khilji is an activist and Chevening Scholar from Pakistan pursuing an MSc in Comparative Politics at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His interests include minority rights, online censorship, civic education, reform in Pakistan’s tribal areas, and peace in South Asia. He tweets @UsamaKhilji and blogs at usamakhilji.com.