The burden of non-communicable, tertiary diseases in India is increasing as its population of prosperous and aged people increases. Private health insurance is largely limited to upper middle class patients, while publicly financed health insurance has failed to attract lower-income patients. New evidence from the Aarogyasri Programme in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh suggests that community networks may provide an important channel to disseminate information and encourage take up of public health insurance, write Tarun Jain and Sisir Debnath.

The burden of non-communicable, tertiary diseases in India is increasing as its population of prosperous and aged people increases. Private health insurance is largely limited to upper middle class patients, while publicly financed health insurance has failed to attract lower-income patients. New evidence from the Aarogyasri Programme in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh suggests that community networks may provide an important channel to disseminate information and encourage take up of public health insurance, write Tarun Jain and Sisir Debnath.

The burden of disease

Apart from quality of life and income, poor health affects the wellbeing of families sociologically and psychologically. The economic burden of bad health is tangible and substantial. For example, out-of-pocket expenditure on treatment and services for HIV/AIDS and antiretroviral treatment in India in 2005, was reported at Rs. 6,000 to Rs. 18,150 per person for a six-month reference period, respectively (Burden of Disease in India, 2005). What’s more, roughly 40% to 70% of this expenditure is financed by borrowing or selling assets.

Approximately one-third of households in India face catastrophic health expenditures where out-of-pocket payments exceed 40% of the household’s ability to pay (Raban et al. 2013). For poorer households, catastrophic healthcare expenditure, followed by temporary or permanent job loss, may effectively lead to impoverishment. Indeed, research estimates that catastrophic healthcare expenditure is associated with a 2.7% increase in extreme poverty in Asia (Van Doorslaer et al. 2006).

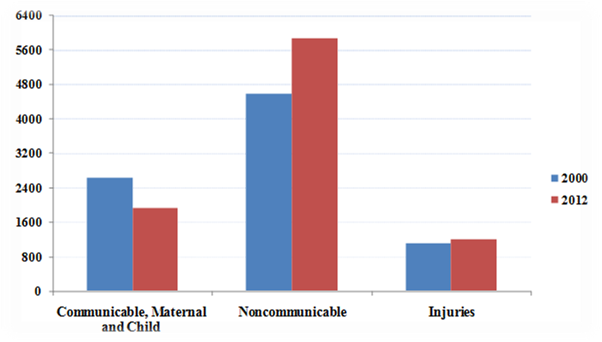

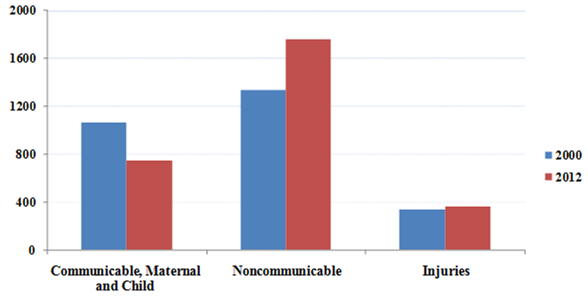

Figure 1: Distribution of the Burden of Disease in India over Time

Panel A: India

Panel B: South Asia

Communicable versus non-communicable diseases

Communicable diseases, maternal and child health conditions account for nearly half of India’s disease burden. Healthcare policies focus primarily on communicable diseases as they pose large negative externalities to society and are usually less resource intensive to address. As a result, the incidence of communicable diseases, such as malaria, tuberculosis, diarrhoea and other infectious diseases has reduced sharply, with polio and leprosy being almost eliminated. The number of deaths from communicable diseases decreased from 2.6 million in 2000 to 1.9 million in 2012 (Department of Health Statistics and Information Systems, WHO, 2014). Meanwhile, non-communicable, tertiary diseases in India and elsewhere in South Asia have increased disproportionately (Figure 1) but received relatively less attention from policy makers.

Tertiary diseases: burden and demand

India’s public interventions toward tertiary diseases are mostly limited to subsidised healthcare services through facilities that are directly owned and operated by the government. In practice, the vast majority of these public healthcare facilities are of poor quality and often crowd out private healthcare providers.

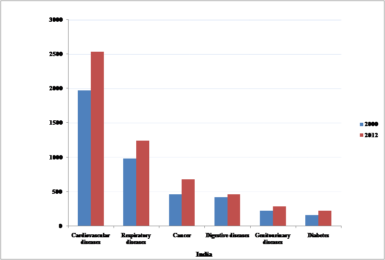

The treatment of tertiary diseases such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases requires better facilities. Additionally, recent trends suggest that the burden of such diseases is slated for a fairly sharp increase, while incidents of death from communicable diseases are on the decline.

Figure 2: Burden of Tertiary Diseases in India over Time

An absence of insurance in developing countries

Insurance against catastrophic health expenditure may increase the ability of economically weaker households to save and invest their way out of poverty. In many developed nations, where insurance markets are developed, health insurance coverage is almost universal. However, in the context of developing countries, despite being heavily subsidised, health insurance coverage is negligible.

In India, 86% of all health expenditure is out of pocket, with only 15% of Indian households reporting any insurance coverage (World Health Organisation 2011). Utilisation of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna (RSBY), a central government operated health insurance programme providing insurance coverage to Below Poverty Line (BPL) households in 25 states, is between 11% and 55% in the district of Amravati in Maharashtra (Rathi, Mukherji and Sen, 2012) and “virtually zero” in the state of Karnataka (Rajasekhar et al. 2011).

Why has the private market failed to deliver?

One reason the private market fails is because only the chronically unhealthy try to enrol, resulting in the premiums quickly spiralling beyond affordability. Another reason may be that poor households do not understand the benefits of health insurance. Finally, households may not trust insurance providers to reimburse claims, especially since few private firms have proven track records in processing and paying claims. In this vein, N. C. Saxena, a former member of the erstwhile National Advisory Council, stated when commenting on the participation of the poor in financial inclusion schemes that, “Typically, people in that strata of society are circumspect about any scheme, which needs them to put in money – simply because they do not trust that they will get this money back.” (Nair, 2016).

Publicly funded programmes: hidden potential?

Publicly funded programmes with cashless transactions and no co-payments or deductibles may have the potential to increase the adoption of health insurance. If premiums are paid directly by the government, trust in the provider and liquidity constraints in paying premiums do not serve as significant barriers to take-up. Furthermore, if coverage is automatic or universal, then understanding programme details is not necessary for eligible populations to obtain insurance.

Even so, the treatment of tertiary diseases relies critically on information, about which specialty hospitals and physicians provide the best care, treatment options, as well as information on how to use the programme. Peers and social networks might be an important channel by which such information is obtained.

The Aarogyasri Programme

The Aarogyasri Programme is a cashless public health insurance programme for BPL households in Andhra Pradesh (and Telangana since the state’s formation in 2014). The programme covers medical bills up to Rs. 200,000 for the treatment of serious ailments such as cancer, kidney failure, heart and neurosurgical disease that require hospitalisation. All transactions are cashless, allowing beneficiaries to go to any authorised hospital and receive care without paying upfront for the covered procedures. The insurance does not have any deductible or co-payment.

The programme is operated by the Aarogyasri Health Care Trust and managed by a private insurance company. Currently, 938 treatments are covered under the scheme. Almost 90% of the population of the two states possesses a BPL card making the programme almost universal. As of December 2013, about 21 lakh (2,1 million) procedures had been performed under the programme, with more than USD800 million claimed cumulatively by beneficiaries.

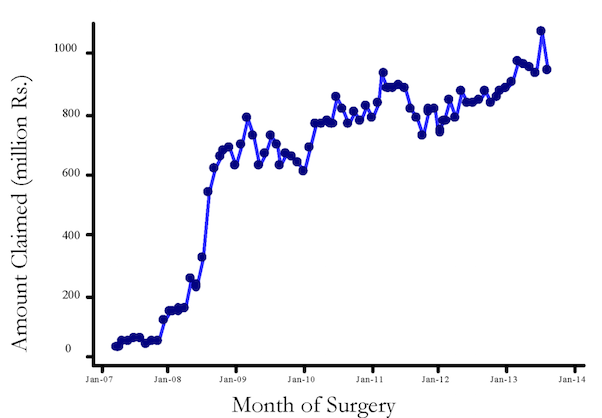

Figure 3: Aarogyasri utilisation over time

Panel A: No. of Surgeries

Panel B: Amount Claimed (In Million Rupees)

Panel B: Amount Claimed (In Million Rupees)

As of May 2014, 663 public or private hospital hospitals were empanelled under Aarogyasri. The Aarogyasri Trust pays healthcare providers on a case-by-case basis at a predefined rate. Hospitals conduct free health camps for patients and help desks facilitate patient access at primary health centres, area/district hospitals and network hospitals.

Learning through community networks

Research has been performed on the Aarogyasri Programme, exploring to what extent caste and gender networks affect the utilisation of publicly-financed health insurance for tertiary care. The analysis suggests that members of the same caste in the same village are important sources of programme information (Debnath, Jain and Singh, 2015). In particular, if caste peers have used Aarogyasri in the previous quarter, then an individual is 19% more likely to claim Aarogyasri benefits for the first-time. Interestingly, other caste groups within the same village, and the same caste members in other nearby villages, had virtually no effect on utilisation. This finding is consistent with healthcare decisions being localised, with immediate family and friends serving as the central sources of information.

The research also found that a range of other factors are complementary to community networks. For example, caste network effects are stronger in urban areas and in regions with greater penetration of cell phones and radios. This implies that proximity to peers, or at least the ability to contact them quickly, greatly facilitates the effectiveness of social networks in providing programme information.

Networks might also be ineffective in disseminating information for diseases that require patients to reveal private and sensitive information to their friends. Conversely, some diseases such as cancer are informationally intense to treat, and patients need the advice of their friends and relatives to make treatment decisions. The results show that network effects are the largest for cardiology, nephrology and urinary surgery, with oncology and pediatrics patients also relying extensively on their peers. In contrast, network effects associated with ophthalmology, plastic surgery, dermatology and gastroenterology are lower, perhaps because decision-making by patients is less complex for these procedures.

The implications for tertiary disease healthcare in developing countries

These findings have implications for strategies to improve the treatment of tertiary diseases in India and other developing countries. By uncovering the role of community networks on healthcare use, the findings suggest that welfare programs should incorporate network based learning, in addition to direct information provision, to increase participation. This approach has been applied in the case of Mahadalits in Bihar with positive results (Kumar and Somanathan, 2015). With respect to publicly financed health insurance, researcher has also found that community liaisons are effective in encouraging enrollment in RSBY (Berg et al. 2013). Future research, with a sharper focus on implementation, could help understand and operationalise the network-based approach to increasing healthcare use.

This post originally appeared on the IGC blog. Original article with full references available here.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

Tarun Jain is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the Indian School of Business.

Tarun Jain is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the Indian School of Business.

Sisir Debnath is Assistant Professor of Economics and Public Policy at the Indian School of Business.

Sisir Debnath is Assistant Professor of Economics and Public Policy at the Indian School of Business.