LSE alumnus and Member of our Senior Advisory Board Ahmed Mushtaque Raza Chowdhury’s personal account of his journey in independent Bangladesh explains the triumphs of the nation against the odds, the challenges that lie ahead, and his own participation in it.

LSE alumnus and Member of our Senior Advisory Board Ahmed Mushtaque Raza Chowdhury’s personal account of his journey in independent Bangladesh explains the triumphs of the nation against the odds, the challenges that lie ahead, and his own participation in it.

If someone asked me which year I would like to travel back in time, the unequivocal answer would be 1969–71. In 1969, I joined the Department of Statistics of the University of Dhaka as a freshman. In those tumultuous days when history was being inked, my alma mater was going to be in the epicentre of what was going to unfold over the next months. Before moving to Dhaka, fearing for my safety, my mother made me give her my word that I would not be part of any active politics. When I arrived, however, given the charged situation, could I really ignore what was happening all around me? I ended up taking part in every major political event that was organised. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s words from the Shaheed Minar (Language Movement monument) on 21 February 1971, and then the fateful speech on 7 March 1 from the Race Course Grounds still echo in my ear as vividly as it did then — about the conspiracy being hatched against the Bengalis, and the impending crisis. And then the war itself which gave us so much — our nationhood. These are some of the memories that make my cohort part of a glorious history.

Yes, the War of Liberation has given us so much. For the past 20 years, like many others, I too have been talking about the gains that we have seen in the socio-economic fabric of Bangladesh — be it education, poverty alleviation, women’s status or health, to the surprise of many sceptics, Bangladesh continues to forge ahead. Most recently, it has moved from ‘least developed’ to ‘developing’ country status. More than 90% of our children get enrolled at primary schools now — with no remaining gender gap. Poverty has been cut significantly, and there is hardly any food shortage. The nutritional status of children and mothers has also recorded improvement. While a quarter of our children were unlikely to see their fifth birthday at the time of independence, this has now reduced to less than 3 per cent. The nation has been able to drastically cut its population fertility rate and is now near the replacement level: in 1971, the total fertility rate was above 6 (children per woman) which has now come down to 2.3.

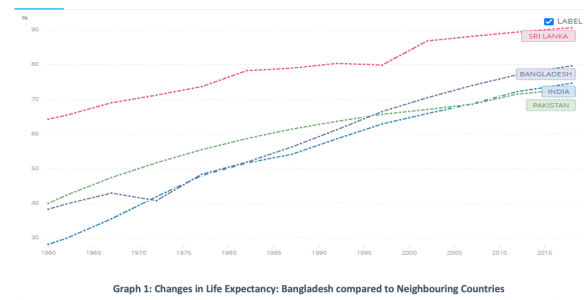

Life expectancy is a robust measure of the wellbeing of a population. In 1971, the life expectancy of an average Bangladeshi was less than 45 years. Since then, it has increased by 70% to 72 years. Until the 1980s, Bangladesh was one of a very few countries where men lived longer than women. As this gender differential is an important marker of progress, I am happy to report that this has now been ‘corrected’, with women living about three years longer than men! The achievement of Bangladesh and the speed at which this has happened can only be compared to the dramatic changes sought in the 19th century Meiji Restoration in Japan. Bangladesh’s socio-economic gains have exceeded those of some of its economically more powerful neighbours. An average Bangladeshi now lives longer than her/his counterpart in India or Pakistan (Graph below).

Source: United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospectus: 2019 Revision.

How has this positive deviance occurred? In 2013, the very prestigious and reputable The Lancet published a series of articles and commentaries on Bangladesh’s progress. The Editors described the Bangladesh experience as ‘one of the great mysteries of global health’. The articles attempted to identify reasons why the country did so well despite other constraints, including economic poverty. As mentioned earlier, an important reason is the War of Liberation itself.

Bangladesh fought out its independence through a protracted struggle which culminated in 1971. The struggle was not only for a piece of land but for freedom. It was a struggle to safeguard its unique heritages of culture, language and secular values. It was a struggle to accord equal rights and respects to all its citizens, including women. The War saw the defeat of not only the foreign occupiers but also its local agents in the guise of religious extremism. The ground was then set for progressive ideas to flourish like according dignity and rightful status to women. Some of the development issues such as family planning, which was deeply contested and to some extent violently opposed by religious fanatics during the pre-1971 period, now had few social obstacles to overcome.

The subsequent governments of independent Bangladesh formulated policies and plans that were sensitive to equity concerns. New investments increased the reach of the health sector through construction of health centres at grassroots level, and the creation of a trained health workforce. For example, there was just one physician per 10,000 population in 1971; this has now increased sixfold. Similarly, non-government organisations (NGOs) trained thousands of community health workers, which increased its density from zero to about six per 10,000 population. Indeed, NGOs played an extensive role, as outlined in The Lancet series of articles. Bangladesh is well-known for its NGOs. In a recent Op-Ed in The New York Times, columnist Nicholas Kristoff has advised the new Biden administration to look to Bangladesh for tackling child poverty in America, and cited the positive role played by organisations like BRAC and Grameen Bank. NGOs’ contributions in implementing nationwide programmes on microfinance, primary education, oral rehydration therapy, family planning, drug policy formulations, vaccinations, etc. in Bangladesh are very well known, and has earned them accolades including a Nobel Peace Prize and a Knighthood! The War of Independence motivated well-educated Bangladeshis to devote their energy to the development of the country and many of them initiated NGOs like BRAC, Grameen and Gonoshasthaya Kendra. Investments in the social determinants of health including women’s empowerment, poverty alleviation, agriculture, primary education, ready-made garments, and infrastructures such as roads and highways have paved the way for impacting on the health status of its citizens. In mitigating the effects of deadly natural disasters, training of volunteers and building of infrastructures (like cyclone shelters) has helped build resilience.

After my graduation, I spent the most part of my professional life with BRAC. Before independence, my aim in life was to follow the footsteps of many university graduates to join the civil service. The War changed my outlook totally as I considered working for BRAC a better way to serve the people in need. Working for BRAC gave me the rare opportunity to directly participate in the various development work that the organisation was delivering, and to see for myself how the lives of common people was being transformed.

Bangladesh has done well. In spite of the gains and a growing economy (average annual growth of 6% for the past two decades), however, there are a number of things that are pulling the country back from reaching greater heights. It is yet to match what our other neighbour Sri Lanka has achieved (Graph 1). Persistence of poverty is a bane with about a quarter of Bangladeshis still poor by any standard. The income inequality is high, and is not lessening. This is related much to issues of governance: corruption in the public sector is amongst the highest in the world. Health and other development sectors are weakly managed, resulting in poor accountability and a haemorrhaging of resources. There is little interest or debate on some of the current or potentially important issues: for instance, with one of the fastest growing urban settlements in the world, of whom a third lives in slums, there is little attention on how to address this. The explosion of lifestyle-related (and other) non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as hypertension, diabetes and cancer will further tax a poorly functioning health system. Environmental pollution and climate change will likely worsen vulnerability, particularly for the poor. Issues such as arsenic in drinking water unfortunately remain neglected or forgotten. The Universal Health Coverage (UHC) to reduce out-of-pocket expenses and consequent poverty has not yet received any serious attention despite repeated governmental promise. Bangladesh has successfully harvested the ‘low hanging fruits’ but addressing the unfinished agenda and future challenges will need a new generation of health systems with increased resources. Bangladesh’s investment in health is the world’s lowest(less than 1% of GDP). The Covid-19 crisis has shown how vulnerable the health system is.

The War of Liberation provided impetus to the country’s forward momentum. It helped reaffirm our faith and commitment to a liberal and modern society. In our journey for a better life for every Bangladeshi, we have done well in some areas. With renewed attention to issues that pull or hold us back, our gains can truly be monumental.

*

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The ‘Bangladesh @ 50’ logo is copyrighted by the LSE South Asia Centre, and may not be used by anyone for any purpose. It shows the national flower of Bangladesh, Water Lily (Nymphaea nouchali), framed in a design adapted from Bangladesh’s dhakai & jamdani textile weaves. The logo has been designed by Oroon Das.

*

A very informative account of Bangladesh’s growth in 50 years. The author having seen Bangladesh getting liberated and progressing to be one of the emerging nations: has personally experienced the nations journey. Hopefully the issues pointed out by the authors will be addressed and the country will make monumental gains.

A wonderful read! So rich in detail of the history of Bangladesh mingled with personal accounts makes this truly enjoyable. Thanks for sharing!

An eloquent testimonial detailing the tumultuous journey Bangladesh took to get such splendid achievement. It also reminds us what yet is left to give to the country we call home.

Really enjoyed reading the road towards development. Thank you.

Well documented. You were part of that memorable history of the birth of Bangladesh and its many challenges. Also you deserve recognition for your own remarkable contributions in public health, education and social development. Keep up the good work.

This is a superb capsulation of a wonderful contribution to the success of Bangladesh yet a recognition of remaining challenges. The Bangladesh Liberation War Museum should highlight this article and send it out to its many patrons. Thanks to Mushtaque for a lifetime of service.

Bangladesh has made an astonishing journey and hopefully the success will continue if the issues mentioned by Prof Chowdhury will be addressed.

Being part of the Embassy of Sweden and Sida, who next year celebrate our 50 th anniversary of our engagement and cooperation with Bangladesh this text is wonderful to read.

Wonderful,narrative in simple word. The sceneriio observed by the writer while work with the poor in remote areas to urban. As quoted he had the opportunity to be apart of development for years as a development worker and PH expert. His story telling style is such – the readers can follow while get the flavour of development in his own concept. The last two paras he has pointed out the causes for backwardness and identified like – gender equity and empowerment of women, income parity while rightly told main major inturuption : governance and corruption. In his article he used data sources of reputed journal beside use graph to show development in various sectors.

Hope researchers will be beniffited and get the the information of recent development of Bangladesh in health which is acclaimed by international standard.

Thanks to Dr AMR chowdhury for writing o piece which in future will be part of history. Request the writer to share his real experiences for those who will work for the poor.

Wish his success in future too

Mahboob Ul Alam Bhuiyan

Former Deputy Director,

Bangladesh Rural Development Board ( BRDB)

5 Kawran Bazar, “ Palli Bhaban”

Dhaka

A wonderful journey. It is like telling story. The reader can’t break reading unless she/he finish reading it. I must thank the author about his observation and empirical evidence of the last about 50 years which make the article very rich. I would like to suggest the author to continue writing.

Shabbir Ahmed Chowdhury

Great to read this! Well written – how growth of a nation and a true national compliments! People need you both more than ever! Heartfelt congrats on this happy occasion of 50 years journey!

Feeling honoured to read this. Great to see how the growth of a nation and a true national compliments. We are proud of you!!

I am overwhelmed to know that you are the part of the history of our independence.

I am indeed very blessed to have the opportunity to get in touch with you. My sincere prayers are always with you.

Thanks for the informative write up about the growth of Bangladesh.

Expecting more from you.

It’s a very positive message from a relatively new country that started from ‘zero’ (the ‘bottomless basket’ of Henry Kissinger of USA) to become, half a century later, a ‘hero’ of the South East Asia and envy of its powerful neighbour India and its previous ‘Master not Friend’, Pakistan! It has surpassed both those neighbours in a number of development indices. It dares to be ambitious enough to take on other neighbours and exceed them in many of these indices in the not too distant future.

However, there’s no room for complacency as it all depends on continued political stability and good relations with all the neighbours, including India who did so much for us during our independence ‘mukti jhodda and indua’s Powerful rival, China, who was with Pakistan to frustrate our independence as much as the super power, USA. Gladly, we are in good terms with all three of them, India, China and USA. This is clearly seen in the influence of USA English in this well articulated blog piece in which the author has used words like Freshman, School etc (despite the existence of LSE in England). The author, who was the Keynote Speaker at the event to celebrate the Fifty years of Bangladesh by Dhaka University Alumni in the UK in December 2020, is a Professor at Columbia University, has been closely associated with some significant input, as a key player at BRAC for the last forty years or so, as the ‘right hand man’ of late Sir Fazale Hasan Abed, the visionary Founder and architect of the Bangladesh wonder, an outstanding Bangladesh achievement called Brac, the largest NGO in the world today.

Muhammad Abdur Raquib, FCA

Essex, England

19/05/2021

Huge invaluable and contemporary information about the country in a brief write up. Thank you for sharing!

Enriched me with huge invaluable information. Thank you for sharing!

A welcome reminder of Bangladesh’s remarkable achievements during its first 50 years. This should spur political leaders on to invest more in the health of the population and work to notch up comparable gains in the next quarter century.

Resourceful information. Thank you for sharing.

Dr. Mushtaque Chowdhury speaks with great credibility. With his background in public health as a visiting faculty at Columbia University, and his decades of work with the world famous NGO, BRAC, he knows the problems and challenges Bangladesh faces as it moves towards the Middle Income status. Indeed, to a large extent it is for citizen-leaders like Sir Fazle Abed, founder of BRAC and Prof. Yunus, Nobel Laureate and founder of Grameen Bank, that Bangladesh stands tall today, haven broken the shackles of extreme poverty as a nation, and moving ahead of both India and Pakistan in many of the human welfare indicators which matter. Bangladesh is so fortunate to have honest and patriotic leaders like him who have given their lives to working for the nation’s upliftment. Despite many challenges, the world is watching Bangladesh as it grows and prospers. Thank you.

Very enlightening and informative writings! Thank you Mustaq Vai! So happy to read your testimonial !!