Decades of punitive crime policies, frequently linked with the ‘war on drugs’, have given the US the highest incarceration rate in the world, with African Americans vastly overrepresented in the prison population. Tim Newburn argues, however, that there may be some small cause for optimism. In a recent speech, the US Attorney-General, Eric Holder, announced changes to the way offenders would be punished, including a desire to reduce the prison population. In addition to Holder’s speech,, the declining use of the death penalty, falling state-level prison populations, and gradual changes to drugs laws, appear to indicate that the politics of punishment in America are beginning to shift.

Decades of punitive crime policies, frequently linked with the ‘war on drugs’, have given the US the highest incarceration rate in the world, with African Americans vastly overrepresented in the prison population. Tim Newburn argues, however, that there may be some small cause for optimism. In a recent speech, the US Attorney-General, Eric Holder, announced changes to the way offenders would be punished, including a desire to reduce the prison population. In addition to Holder’s speech,, the declining use of the death penalty, falling state-level prison populations, and gradual changes to drugs laws, appear to indicate that the politics of punishment in America are beginning to shift.

Three weeks ago, US Attorney-General, Eric Holder, announced potentially significant changes to the ways in which the American federal government punishes offenders. In his speech in which he proposed a significant reduction in the use of mandatory minimum sentences against low-level drug offenders, Holder took aim at US penal policy describing levels of imprisonment in the US as both ‘ineffective’ and ‘unsustainable’. To understand the Attorney General’s observation one must appreciate the scale of what has been happening in the US in the last 30 years and why some commentators have come to refer to it as an experiment in ‘mass’ incarceration.

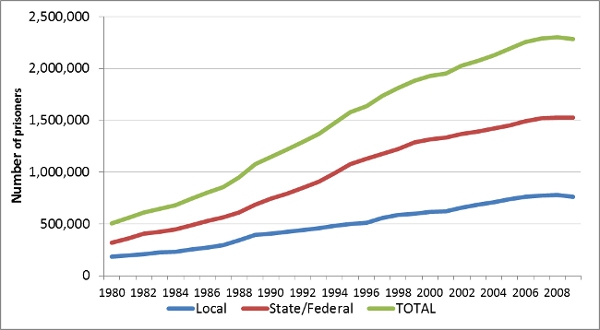

In 1980 the American prison population totalled just over half a million. Adding probation and parole the total ‘correctional population’ was 1.8 million – relatively high by international standards but not off the scale. As shown in Figure 1, by 2009 the prison population had swollen to almost 2.3 million and the total number under correctional control was nearly 7.25 million (a greater ‘population’ than Massachusetts or Arizona).

Figure 1 – US Prison Population, 1980 – 2009

Source: Felon Voting

Source: Felon Voting

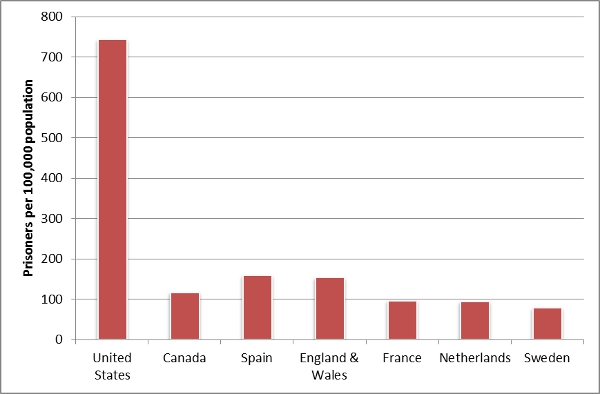

Looked at comparatively, the scale of what has been happening in the United States is quite unlike any other developed country. Despite close to a doubling of the prison population in the UK in recent decades, and very sizeable increases in incarceration in other Western European nations, none of them begins to compare with the rate at which America imprisons its citizens, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 – Comparative incarceration rates across countries in 2011

Source: Walmsley, R. (2012) World Prison Population List, Essex: ICPS

Source: Walmsley, R. (2012) World Prison Population List, Essex: ICPS

America’s unparalleled incarceration rate led the US Bureau of Justice to estimate that if left unchanged 6.6% of all American citizens born in 2001 would face imprisonment in their lifetime. Frightening though such a figure is it masks the extraordinarily unequal distribution of risk. In reality, while white males born in the US in 2001 would have a 1 in 17 chance of imprisonment, the odds lowered to 1 in 6 for Hispanic males and to an astonishing 1 in 3 for black males.

The roots of America’s punitive turn and of the colossal racial disparities at its heart are complex, but the ‘war on drugs’, announced by President Nixon in 1971 and which has raged for much of the period since, must occupy a central role in any explanation. As Michelle Alexander documents so forcefully, over a period of three decades the war on drugs in effect became a war on poor urban communities of colour. On top of very significant increased likelihood of arrest for drug law violations, young black males in the US also found themselves the target of a succession of punitive mandatory minimum sentencing policies, particularly applying to drug offences. Prior to the introduction of Federal mandatory minimums average sentences for black offenders were 11% higher than for white offenders. Since 1986, federal drug sentences have been nearly 50% higher for black offenders. The end result, as Alexander so graphically puts it, is that there are now more African American men in prison, jail, on probation or parole, than were enslaved in 1850 prior to the Civil War.

All of which brings us back to the Attorney-General’s statement. He announced a shift in sentencing policy, a desire to reduce the prison population, and to significantly increase the use of alternatives to imprisonment. In so doing he was outspokenly critical of current penal policy, observing that ‘too many Americans go to too many prisons for far too long and for no truly good law enforcement reason’.

Two things are noteworthy about Holder’s speech. The first is that the announcement was made at all. Most obviously it goes against the decades-long punitive drift of penal policy in the US (and elsewhere). Politicians – Democrat and Republican – have generally sought to parade their ‘tough on crime’ credentials believing it to be a vote-winner and, indeed, have generally acted on the assumption that any other stance was tantamount to electoral suicide. For the Attorney General therefore to be publicly critical of America’s incarceration binge may be a signal that the politics of crime is changing – and changing in a way that for years felt impossible.

More remarkable – and a sign that something very significant may slowly be taking place – is that Holder’s announcement was greeted, not by fury and condemnation – which would have been expected at pretty much any time in the past quarter century – but by a large measure of agreement and of something close to bipartisan support. Far from being accused of being ‘soft on crime’, Holder’s announcement has generally been received as worthy of serious consideration and has been the subject of broadly tolerant debate. In truth, there have been wider signs of change for some time.

First, the US state-level prison population is in decline. True, the decline in 2012 was only 1.7%, but it was the third year in a row there had been a drop and is clearly not a blip. Though the Federal prison population has been rising – and it is this Holder aims to change – in 2010 Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act which reduced the vast disparity in the way federal courts punished crack as against powder cocaine offences, leading to reductions in sentences for thousands in federal prisons – the majority African-American. The state level declines have been hugely influenced by three states, and by California in particular – a court order having forced its legislature to slow down the rate of admissions. But at least 25 other states have also seen their prison population drop, with fairly radical reforms occurring in states such as Florida, Texas, Kansas and New York. In the latter case changes to the notorious Rockefeller drug laws appear to have played a significant part in the State’s significant prison reductions.

And it is not just imprisonment. Whilst one of the regularly used illustrations of American ‘exceptionalism’ in the penal sphere is the continued use of the death penalty, the reality is that it is in continuous decline. Eighteen states have abolished it entirely, the most recent being Connecticut in 2012 and Maryland in 2013. Although the remainder retain it for now, a significant number never use it. Indeed, since the death penalty was reintroduced in the late 1970s, over three-quarters of all executions have occurred in just eight states, and Texas alone accounts for 37% of the total. Drugs too. In the last year, two states, Washington and Colorado, passed ballot initiatives to legalize the production, distribution and sale of marijuana for adults – a decision that the Attorney General is allowing to proceed. Twenty states have legalized marijuana for medical purposes. The impact of these changes may not yet be huge, but symbolically they are a world away from Nixon’s war on drugs rhetoric.

The reasons for the changes are not entirely clear. Undoubtedly finance and budgetary considerations have been important. The sheer scale of the American incarceration boom has left some states with future financial costs they have little chance of being able to meet without slashing other areas of public expenditure – including public education. In addition, we shouldn’t forget that crime has been in decline for some time: violent crime in the US dropped 15% between 2002 and 2011, and property crime nearly 20% in the same period. This has undoubtedly been a factor in opening up a space in which progressive law reform – visible just as strongly in many Red states as Blue – can begin to gain a foothold.

It’s important not to get too carried away in all this. The United States still accounts for close on one quarter of the world’s incarcerated population. The number of prisoners on death row – currently over three thousand – remains stubbornly high and the continued availability of firearms leaves America with a homicide rate nearly three times that of Canada and four times that of the UK. Nevertheless, after years in which social scientific discussion of US penal policy and practice has been almost entirely dystopian, it seems now the green shoots of a more optimistic future are beginning to emerge.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/138j4yu

_________________________________

About the author

Tim Newburn – LSE Social Policy Department

Tim Newburn – LSE Social Policy Department

Tim Newburn is Professor of Criminology and Social Policy, London School of Economics. He is the author or editor of over 30 books, including: Handbook of Policing (Willan, 2008); Policy Transfer and Criminal Justice (with Jones, Open University Press, 2007); and, Criminology (Routledge, 2013). He is currently writing an Official History of post-war criminal justice, and was the LSE’s lead on its joint project with Guardian: Reading the Riots. He tweets at @TimNewburn.

There is much more in the US Attorney General´s speech to the American Bar Association in August 2013 than the admission that too many Americans go to prison for far too long for no good law enforcement reason.

Saner approach to drug policy

Yes he will not use federal laws to attempt to trump state decriminalization of marijuana in Colorado and Washington. Yes he may be open to stopping federal harassment of laws that allow medical use of marijuana in 18 States. All progress unimaginable only two short years ago.

These are actions that save taxpayers money without increasing violence. Indeed, these smart actions are getting lots of encouragement, among others from the New York Times on saner approaches to drug laws and the Organization of American States that praised the reforms to the criminal justice system that will reduce use of incarceration.

A saner approach to criminal justice

But his speech was much bolder than media headlines on avoiding waste of criminal justice funds to control marijuana. It potentially shifts US federal criminal justice policy from earlier decades where it provided incentives to the states and local government to increase the use of incarceration to rates unimaginable in any other affluent democracy.

He admitted that US criminal justice may exacerbate ¨a vicious cycle of poverty, criminality, and incarceration¨. He referred to racial bias. Nevertheless, the Economist published the view that his ideas did not go far enough.

He did not say that too many young Americans are victims of too much violence because of too many failed policies. Nor did he directly say what he would do about these failures – remembering that the failure to reduce homicides and violence is a much bigger contributor to mass incarceration even than drugs.

However, juvenile justice commitments are dropping as fast as the arrest rates, as are jail populations in New York City. All showing that bringing rates of incarceration down to rates of the 1990´s is happening somewhere, some of the time.

A saner approach to preventing violence

But he did use ¨PREVENTION¨ in his vision of getting results for victims and avoiding waste to taxpayers. His speech was very much indicating prevention that is about protecting potential victims from violence. He recalled the need to look at ¨why young black and Latino men are disproportionately victims¨. He called attention to ¨violence spikes in some of our greatest cities. As studies show that six in ten American children are exposed to violence at some point in their lives¨.

He mentioned that the President had been a community organizer in South Side Chicago. He praised the ¨landmark Defending Childhood Initiative and the National Forum on Youth Violence Prevention¨. He will get every US District Attorney a Prevention (and Reentry) Coordinator! All vital steps in the right direction of adding effective prevention to law enforcement as a way to promote public safety.

But he is sitting on a gold mine that he did not mention. His department´s website on crime solutions and other sources of proven crime prevention strategies. There are also important guidelines from UNITY and the experience of Los Angeles, Minneapolis and other cities that have shown that violence in cities can be prevented from partnerships between police and social outreach that tackle violence at its roots, using a public health approach.

Saner ways of stopping violence against women

He drew attention to a startling statistic to most parents of university girls that one in four college women will be victims of sexual assault by graduation. Again he did not tell us what he would do, but his department´s website does, as do many experts. If every college and university adapted the proven practices such as 4th R and Green Dot that reduce this violence, university studying would be safer for women.

A Time for Public Safety Reinvestment

His speech makes a compelling case to shift federal funds from over-reaction against offenders to cost-effective prevention for victims. The White House has already promised investments in early education – $1 for $7 – and in school based substance abuse prevention – $1 for 18 . Why not $1 for $10 in juvenile delinquency prevention.

Think how many fewer (African, Latino, White …) Americans would be victims of violence, if the federal government moved to get results by investing in effective violence prevention and supported States that wanted to do the same. Think how many taxes would not be wasted.

Saner drug policies, saner criminal justice policies, saner violence reduction strategies – all smarter in protecting victims and avoiding wasted taxes – make way for Smarter Crime Control.